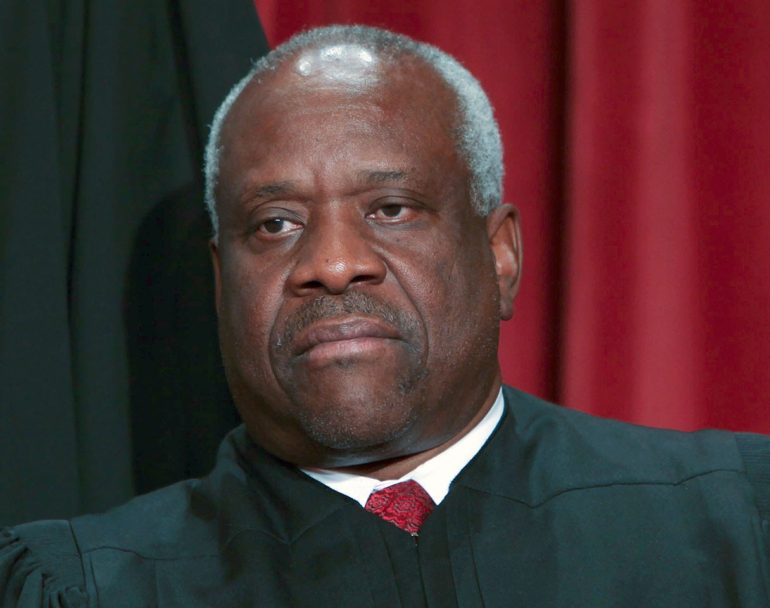

Justice Thomas’s Credo

The Constitution, not precedent, is the law of the land

by Myron Magnet

One of the most striking aspects of Monday’s Supreme Court decision in Gamble v. United States was Clarence Thomas’s eloquent summary of the core precept of his judicial philosophy: that stare decisis—the venerable doctrine that courts should respect precedent—deserves but a minor place in Supreme Court jurisprudence. His 17-page concurrence in a case concerning double jeopardy, really a stand-alone essay, emphasizes that, in America’s system of government, the “Constitution, federal statutes, and treaties are the law.” That’s why justices and other governmental officers take an oath to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States”—not to safeguard judicial precedents. “That the Constitution outranks other sources of law is inherent in its nature,” he writes. The job of a Supreme Court justice, therefore, “is modest: We interpret and apply written law to the facts of particular cases.”

Unlike the unwritten English constitution that governed the American colonists for 150 years before the 1787 Constitutional Convention rejected it, U.S. law does not “evolve” by the slow accumulation of judicial precedents. What the law schools teach as “constitutional law” is merely a collection of opinions valid only insofar as they correctly construe the written texts of the Constitution and statutes. Moreover, as Thomas explains in Gamble, even English common law judges, who saw their job as “identifying and applying objective principles of law—discerned from natural reason, custom, and other external sources—to particular cases,” recognized the possibility of error, making it their duty, as Thomas quotes James Kent, a celebrated jurist of the early republic, to “‘examin[e] without fear, and revis[e] without reluctance,’ any ‘hasty and crude decisions,’ rather than leaving ‘the character and harmony of the system destroyed by the perpetuity of error.’” English jurist William Blackstone had put it even more strongly in his standard Founding-era law text, Thomas observes. “When a ‘former decision is manifestly absurd or unjust’ or fails to conform to reason,” Blackstone pronounced, “it is not simply ‘bad law,’ but ‘not law’ at all.”

So, if even English judges, working in a precedent-based common-law system, see themselves as duty-bound to overturn earlier decisions that they consider erroneous, why would American Supreme Court justices, for whom precedent is only a guide, not a command, be any less ready to do the same? After all, they don’t hesitate, when they deem unconstitutional a law passed by the people’s elected representatives and signed by the president, to overturn it. “In my view,” Thomas declares in Gamble, “if the Court encounters a decision that is demonstrably erroneous—i.e., one that is not a permissible interpretation of the text—the Court should correct the error. . . . When faced with a demonstrably erroneous precedent, my rule is simple: We should not follow it.”

Current Court doctrine, however, holds that the justices should balance other factors before deciding to overturn a precedent—such as “the antiquity of the precedent, the reliance interests at stake, and of course whether the decision was well reasoned,” in Thomas’s words—even, as Justice Stephen Breyer once put it, “whether a precedent ‘has become well embedded in national culture.’” Such considerations supposedly promote “the evenhanded, predictable, and consistent development of legal principles.” But all this is beside the point. “In our constitutional structure, our role of upholding the law’s original meaning is reason enough to correct course,” Thomas writes. The oft-made “reliance interest” part of this argument—that overruling precedent breeds uncertainty in those who have relied on this or that illegitimate ruling—is particularly specious. “As I see it,” Thomas writes, “we would eliminate a significant amount of uncertainty and provide the very stability sought if we replaced our malleable balancing test with a clear, principled rule grounded in the meaning of the text.”

The ills of the Court’s use of stare decisis far outweigh any supposed benefits. A demonstrably false precedent yields precisely the opposite effect from what the Court is supposed to produce: instead of interpreting law, it in effect makes law—and judges are not legislators. Preserving such an erroneous precedent compounds the harm. It “both disregards the supremacy of the Constitution and perpetuates a usurpation of the legislative power.”

Of course, it’s just this usurpation that judicial proponents of stare decisis generally are trying to protect. Usually invoked when it is “least defensible,” the doctrine “has had a ‘ratchet-like effect,’ cementing certain grievous departures from the law into the Court’s jurisprudence.” At the top of Thomas’s list of deplorables is the doctrine of “substantive due process”—the assertion that the due-process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment makes some individual rights so fundamental that no state government can invade them. As Thomas had previously objected, “this fiction is a particularly dangerous one” because it “lack[s] a guiding principle to distinguish ‘fundamental’ rights that warrant protection from nonfundamental rights that do not,” allowing judges to make up imaginary rights out of the Constitution’s supposed “emanations, formed by penumbras”—gas and shadows, in plain English. The end result of such so-called reasoning is the standard set forth in a case like Planned Parenthood v. Casey, for example, which “is the product of its authors’ own philosophical views about abortion,” Thomas writes, with “no origins in or relationship to the Constitution.”

Worse, the Court cooked up the idea of “substantive due process” as a workaround, after two monstrous and bizarre 1870s Supreme Court decisions nullified the Fourteenth Amendment’s “privileges-or-immunities” clause—the protection of all the rights contained in the Bill of Rights with which the amendment aimed to cloak freed slaves against depredations by state governments. After nearly 400,000 Union soldiers had died to make men free, the Supreme Court thus illegitimately paved the way for 90 years of Jim Crow black serfdom in the South. “I have a personal interest in this,” Thomas once said. “I grew up under segregation,” in Savannah. How different his own, and the nation’s, history would have been had the Supreme Court allowed the Fourteenth Amendment, as its framers and ratifiers intended, “to perfect a blemish on this country’s history,” Thomas once said. “That is the blemish of slavery.” But, Thomas objects in Gamble, “the Court refuses to reexamine its jurisprudence about the Privileges or Immunities Clause, thereby relegating a ‘clause in the constitution’ ‘to be without effect.’ . . . No subjective balancing test can justify such a wholesale disregard of the People’s individual rights protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Five years ago and more, such legal commentators as Philip Howard or Mark Levin saw no other way to restore our original Constitution—the one framed in 1787, improved by the Bill of Rights, and perfected by the Reconstruction Amendments and the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the vote—than to call a new convention, as authorized by Article V of the Constitution. Such a conclave would sweep away the many judicial distortions and subversions and bring back our revolutionary, still avant-garde Constitution that doesn’t rule citizens but merely protects their right to govern themselves and to pursue their own happiness in their own way, in their families and local communities. Clarence Thomas has proposed another, more incremental way to achieve that end. In his 28 years on the Court, he has marked out an array of erroneous precedents that he thinks the Court should overturn in order to get back to the Framers’ Constitution. With some new originalist jurists now joining Thomas on the high bench, the Court might just follow the trail back to liberty that he has blazed—and marked out with especially vivid clarity in Gamble.