The First Amendment’s Wall of Separation

By: Mike Maharrey

In an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church and State.”

Jefferson was, of course, referring to the First Amendment. He perhaps overstated his case.

The amendment was intended to prohibit the federal government from establishing a national church and to prevent Congress from legislating on religious matters. Of course, Congress had no such authority to begin with. The Constitution didn’t delegate any authority to Congress to establish a church or to regulate religious matters at all. The First Amendment simply made explicit an implicit truth built into the Constitution.

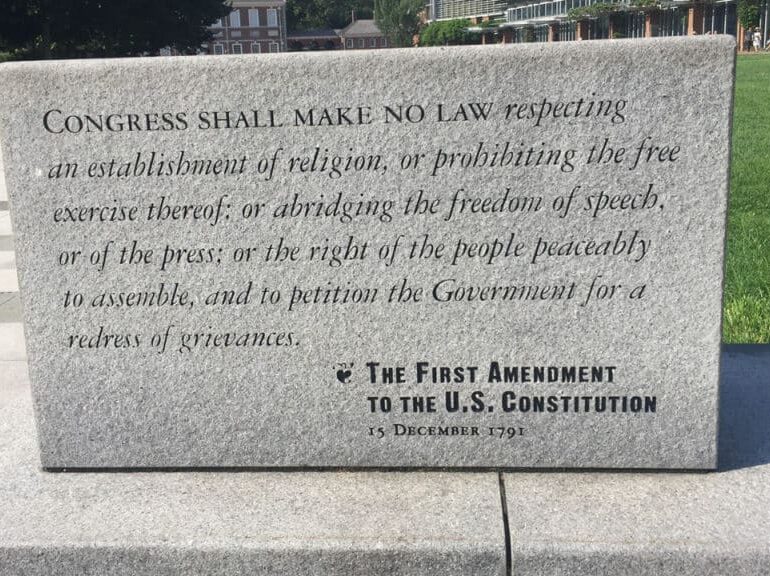

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

The establishment clause of the First Amendment is probably the provision in the Bill of Rights most twisted from its original purpose. People have taken Jefferson’s words and used them as a basis to exile any religious expression from the public sphere at the federal, state and local levels. Whether not you think the absolutism of Jefferson’s wall is positive or negative, it was never the intention of the First Amendment. Jefferson’s wall was only meant to wrap around the federal government.

Through the bastardization of the 14th Amendment, federal judges transformed it into a massive federal billy club used to control religious expression at the state and even the local level. What was intended to limit the reach of the general government was transformed into a massive expansion of federal authority.

During the ratification debates, many skeptics expressed concern that the Constitution did not include a provision prohibiting the establishment of a national religion. New York ratifying convention delegate Thomas Tredwell said he considered the possibility of a national religion a dreadful tyranny.

“I could have wished that sufficient caution had been used to secure to us our religious liberties, and to have prevented the general government from tyrannizing over our consciences by a religious establishment – tyranny of all others most dreadful, and which will assuredly be exercised whenever it shall be thought necessary for the promotion and support of their political measures.”

Supporters of ratification dismissed these concerns, arguing that since the Constitution did not delegate any authority over religion to the new government, it could not possibly interfere with religious freedom.

Rep. Roger Sherman of Connecticut expressed this line of thought during a debate on the amendment in the U.S. House, saying, “It appears to me best that this article should be omitted entirely. Congress has no power to make any religious establishments, it is therefore unnecessary.”

James Madison acknowledged the validity of this argument when he initially proposed amendments but echoed the fears of many that without express prohibition, Congress might invade the rights of the people.

“It has been said that in the federal government they are unnecessary, because the powers are enumerated, and it follows that all that are not granted by the Constitution are retained: that the Constitution is a bill of powers, the great residuum being the rights of the people; and therefore a bill of rights cannot be so necessary as if the residuum was thrown into the hands of the government. I admit that these arguments are not entirely without foundation; but they are not conclusive to the extent which has been supposed. It is true the powers of the general government are circumscribed; they are directed to particular objects; but even if government keeps within those limits, it has certain discretionary powers with respect to the means, which may admit of abuse to a certain extent.”

The “necessary and proper” clause, along with treaty powers, were both brought up as possible vessels that the federal government could use to establish a religion or infringe on free exercise thereof.

During a debate on amendments, on Aug. 15, 1789, Madison explained the meaning of the religious clause as recorded in the congressional record.

“Mr. Madison said he apprehended the meaning of the words to be, that Congress should not establish a religion, and enforce the legal observation of it by law, nor compel men to worship God in any manner contrary to their conscience; whether the words are necessary or not, he did not mean to say, but they had been required by some of the state conventions, who seemed to entertain an opinion that under the clause of the Constitution, which gave power to Congress to make all laws necessary and proper to carry into execution the Constitution, and the laws made under it, enabled them to make laws of such a nature as might infringe on the rights of conscience, or establish a national religion, to prevent these effects he presumed the amendment was intended, and he thought it well expressed as the nature of the language would admit.”

Notice there was no mention of protecting religious freedom in the states. This was not even contemplated. That was considered a role left to the states.

In fact, several states did involve their governments in religion. For instance, the Massachusetts state constitution asserted that “the happiness of a people, and the good order and preservation of civil government, essentially depend on piety, religion and morality,” and provided for the collection of a tax with funds distributed for support of religious organizations of the taxpayer’s choice. By prohibiting Congress from establishing a religion, it was understood that it prohibited any law that would interfere with state religions where they still existed.

The original amendment language proposed by Madison included the words, “nor shall any national religion be established.”

“Mr. Madison thought if the word national was inserted before religion, it would satisfy the minds of honorable gentlemen. He believed that the people feared one sect might obtain a preeminence, or two combine together, and establish a religion to which they would compel others to conform; he thought if the word national was introduced, it would point the amendment directly to the object it was intended to prevent.”

Madison ultimately withdrew the word “national” because of concerns that it could be misconstrued to imply that the Constitution created a consolidated national government as opposed to a federation of states.

During ratification debates in North Carolina, state convention delegate James Iredell addressed the question as to why the Constitution didn’t guarantee religious freedom to the states.

“Had Congress undertaken to gauranty religious freedom, or any particular species of it, they would have had a pretense to interfere in a subject they have nothing to do with. Each state, so far as the clause in question [gauranty of a republican government], must be left to the operation of its own principles.”

The federal government’s use of the First Amendment to prohibit religious displays in local parks, to force the removal of the Ten Commandments from public schools, or to ban prayers in public assemblies would horrify the founding generation. While some may have recoiled at public religious expression, they never contemplated the federal government policing state and local governments. They viewed the centralization of power as a greater danger than potential abuse by state governments, and they considered it the responsibility of the people of the states to police their own state governments.

Modern legal scholars justify this massive expansion of federal power in the domain of states and localities through the Incorporation Doctrine.

Religious freedom was based on an even more basic right – liberty of conscience. In the Aeropagitica (1644) John Milton called for “the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties”

In its simplest form, liberty of conscience means that every person possesses an unalienable right not only to hold their own religious, moral and ethical views, but to act on them free from the coercion of others. William Penn put it this way.

“By Liberty of Conscience, we understand not only a mere Liberty of the Mind, in believing or disbelieving this or that principle or doctrine; but ‘the exercise of ourselves in a visible way of worship, upon our believing it to be indispensably required…”

Religious liberty primarily grew out of a theological idea. John Locke developed the principle in A Letter Concerning Toleration, first published in 1689. At the time, obedience to the state religion dominated political thought. While Locke wasn’t the first to call for tolerance, and he certainly didn’t weave what we would consider a comprehensive philosophy of the principle (he excluded atheists and to some degree Catholics), his thinking was still quite radical for its time, and it had a profound impact on the founding generation in America. Locke held that since God does not force a person to submit to him, it follows that nobody possesses any right to force another to submit to a religious doctrine, including civil magistrates.

“The care of souls is not committed to the civil magistrate, any more than to other men. It is not committed unto him, I say, by God; because it appears not that God has ever given any such authority to one man over another, as to compel anyone to his religion…All the life and power of true religion consists in the inward and full persuasion of the mind…The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force; but true saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God.”

Even before the publication of A Letter Concerning Toleration, there was a push for religious freedom in the colonies. Rhode Island founder Roger Williams and his companions bound themselves by a compact “to be obedient to the majority only in civil things.” And in 1649 Maryland passed the Maryland Toleration Act, mandating religious tolerance for Trinitarian Christians.

In the years leading up to ratification, legislatures in several states engaged in heated debates about the extent of religious liberty, and the idea of toleration was rapidly taking hold. The establishment and free expression clauses reflect this evolution in thought and were meant to prevent the new government from establishing a religion for the United States, or from favoring one sect over another, and to prohibit Congress from passing laws that would punish or politically exile Americans for worshiping as their conscience dictates.

—-

This article was adapted from Michael Maharrey’s book “Constitution Owner’s Manual: The Real Constitution the Politicians Don’t Want You to Know About.” You can get more information about the book at ConstitutionOwenersManual.com.