Melville’s Thoughts on Liberty

by John E. Alvis

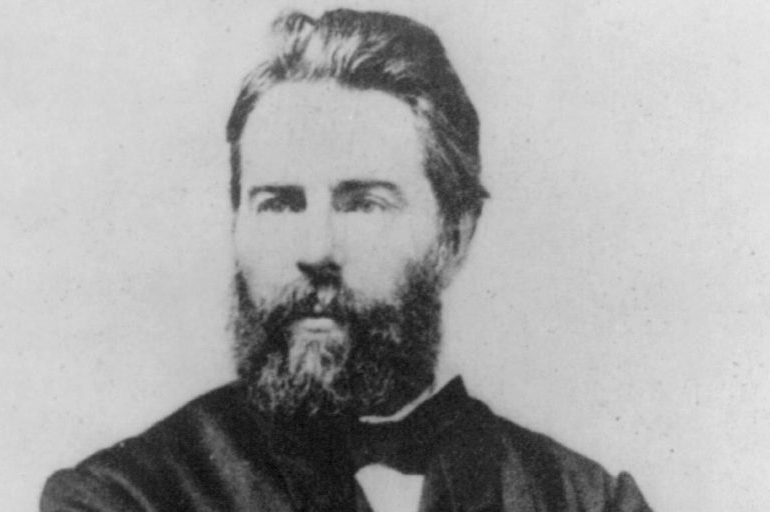

It’s the bicentenary of the birth of one of America’s greatest authors, Herman Melville. We ought to celebrate by examining how Melville, in his poetry and in his prose fiction, conducts an imaginative inquiry into the nature of liberty and the conditions bearing upon man’s access to, and exercise of, his freedom.

I say “inquiry” because Melville characteristically insists upon taking up the other side of any issue—particularly so, when he turns to considerations of political liberty. His inquiry begins with the early allegorical and political novel Mardi, and a Voyage Thither (1849), continues up through his first collection of poems (Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War, published in 1866), and returns once more with the last fiction he would undertake. Born in 1819 in New York City, Melville died a little-noted writer in that same city in 1891, just after penning what would become, together with Moby-Dick, his most popular work. I refer of course to the posthumously published novella, Billy Budd, Sailor (1924).

Poems and Allegory

Let us start with Battle-Pieces and Mardi. The two opening poems of Battle-Pieces announce Melville’s belief that political liberty for slaves and for non-slaves alike is at stake in America’s Civil War. From the first poem of this series we can gather what Melville thought was at issue: “The tempest bursting from the waste of Time/ On the world’s fairest hope linked with man’s foulest Crime.”

On the one side, chattel slavery threatens the fairest hope. A passage in Mardi appears designed to associate this “foulest crime” with inconsistency in respect of national first principles. The inhabitants of the imaginary republic of Mardi profess their devotion to a founding document which holds that “all men are created equal.” Yet they have made an exception with respect to the “tribe of Hammo,” the members of which they consider inferior. Thus Melville indicates that by perpetuating slavery, the Southern states and their sympathizers in the North have violated the nation’s founding principle.

On the other side, that of the Union, the prospects for finding champions to sustain the world’s best hope do not inspire the poet with confidence. He must doubt whether Americans, a people who “prosper to the apoplex” (a phrase from the first poem of Battle-Pieces), will put at hazard their present prosperity to make the sacrifices required of them in the impending struggle: “Dashed aims, at which Christ’s martyrs pale/, Shall Mammon’s slaves fulfill?”

As well as the nation’s having traduced its Founding principles by perpetuating slavery, the very success of Americans in exploiting their unprecedented freedom of enterprise now threatens their devotion to a liberty that combines the right to acquire property with those other inalienable rights which the Declaration of Independence had held human beings possess by natural law and by their Creator’s having so endowed humanity.

In voicing this fear, Melville resembles Abraham Lincoln, whose statesmanship centered upon his conviction that the war challenged citizens to produce a “new birth of freedom.” That revival he expected to be accomplished by recovering the dedication which had produced America’s founding Revolution of 1776. Much later in the sequence, Melville presents an epitaph honoring the assassinated President, a eulogy that has Melville expressly crediting Lincoln with martyrdom.

Moby-Dick (1851), his master work, features a central character who seeks to assert a freedom he conceives as independence against the whale who had taken off his leg. Yet Captain Ahab, in seeking to destroy the white whale, intends thereby to declare his rebellion against the God he has imagined to be the “principal” on whose behalf the whale has only served as “agent.” He imagines the beast to have been employed as an instrument of divine judgment meant to humble him. To that chastising providence Ahab responds with defiance. In the various actions he thinks required for mounting his defiance, he subjects the crew of his ship to his personal quest, in the course of which he violates their natural rights so that he may exact his vengeance against what he supposes to be a tyranny imposed by an oppressing deity regarding whom he boasts, “I’d strike the sun itself if it insulted me.”

Melville makes Ahab a modern Prometheus who prides himself upon acting on behalf of mankind in providing an example of heroic resistance. Yet in this tragic character we recognize what constitutes a perverse version of freedom. For Melville, the pursuit of freedom must be so conducted as to acknowledge and observe cognate responsibilities.

In his depicting Lincoln as a leader corrective to Ahab, Melville means to suggest that a liberty to discharge duties is the most valuable of freedoms. He appears to dispose his readers to find in liberty not an absolute good but, rather, a power to act which deserves honor to the extent it allies with some morally respectable purpose. One could conclude that for Melville, man’s freedom is his greatest instrumental good because whether exercised for good or for ill, it is the faculty which distinguishes human beings from the lower animals.

Moral Freedom Achieved

The various forms of human liberty—their reach and the limitations to which they are subject—Melville treats in his final work, Billy Budd, which is set in the late 1700s. A contest between nations over political liberty provides the enveloping action for this fictive account of a particular crisis within the British navy. The contenders are France under the revolutionary Directory, and Britain, which in 1797 has just undergone two revolutions of its government, and is now “all but the sole free conservative one of the Old World.”

Melville characterizes Americans of that period as interested observers of the conflict while divided in their sympathies for British or French. Two decades after their own Revolution, the Americans view France as a partner in asserting freedom with equality yet distrust the radical and atheistic direction taken by the French revolutionaries. Britain they view as advocate of a liberty that aims, not as does France at a reordering of society in favor of the unpropertied, but a regime dedicated to an ideal Melville identifies with “founded law and freedom defined.”

He makes clear that America, land of the forefathers who “had fought at Bunker Hill,” had by this time come to fear a France commanded by Napoleon, a “portentous upstart from the revolutionary chaos who seemed in act of fulfilling judgment prefigured in the Apocalypse.” Melville seems to suggest that, of the three constitutions figuring in the tale, America’s excels because it shares with France a devotion to natural rights but combines that universalism with traditions of rule of law, due process, separation of powers, and divided legislature, all cultivated to some degree by Britain.

Together with these political considerations, Melville throughout Billy Budd directs attention to liberty in its most fundamental aspects by constructing a plot wherein the interactions of three of his characters reveal something of the nature of liberty as a moral attainment, as a good to be won against adverse circumstance. At issue here is freedom in the sense of personal self-government, self-command. Its fruition entails the liberation of the better part of the soul from the worse—from passion, ignorance, and partiality—all for the sake of securing justice. Character and incident are used to emphasize the pressures that work to frustrate such liberating effort.

This tale is a study of freedom under conditions disadvantageous to its exercise. That would be true of any ship at sea, but we see it demonstrated here through members of the crew of the British warship Bellipotent: through the mid-level surveillance officer Claggart, and the co-protagonists, Billy and Captain Vere. The fates of all three depend upon the outcome of a drumhead trial presided over by Vere wherein Billy must answer for having fatally struck Claggart at the moment the latter had falsely accused him of inciting mutiny.

Each man must contend against circumstances that conspire against his ability to act in a way that is consistent with moral freedom. Common to all three characters are exigencies of warfare, which narrow margins for error. In the setting that Melville imagines, recent history has added another confinement. Britain fights in a kind of war that, because it involves class conflict, threatens the mutual interests of British gentry and commoners by setting the two classes at odds, with common sailors pitted against gentlemen officers. (One such clash had occurred in real life at the time in which the story is set, the nearly disastrous mutiny at the Nore anchorage.)

Still another exigency is tactical and local. When Claggart accuses Billy, the vessel has just encountered an enemy frigate more swift than Bellipotent. This scout ship may presently return backed by the entire French fleet. This means Vere and his officers must decide quickly and cannot risk postponing the court martial until it could be conducted, as Vere would prefer, upon return to the full squadron thereby enabling a less urgent deliberation under supervision of the admiral.

Innocence Versus Natural Depravity

Besides these circumstantial restrictions, Melville has included inhibitions to free choice that come from the personalities of the three men. First we have Claggart, a soul who may be unique in Melville’s fiction for personifying motiveless malignity. No particular grievance has set him against Billy. To account for the surveillance officer’s hatred, Melville must resort to theological conceptions of evil. He instances a depravity said to be “utter,” or in another place “natural.” (The narrator’s playful attempt at definition: “natural depravity—a depravity according to nature.”) Insofar as Claggart’s antipathy is otherwise specified, he is said to despise Billy’s physical beauty and his “innocence.” We must conclude Claggart’s innate character renders him incapable of moral freedom.

Claggart’s victim Melville does credit with innocence, in both senses of the word. Billy is guiltless of malicious intent as well as preternaturally naïve. We are given nothing regarding his origins other than the information that he was a foundling. Melville’s summarizing assessment: “though not a dove he had nothing of the serpent in his make-up.” Billy seems capable, however, of moral freedom. He does deliberate upon what duty requires of him. He displays indignation when a shipmate attempts to induce him to participate in a conspiracy. His one physical impairment—in severe agitation, he loses his voice—causes him to strike Claggart a single mortal blow in reaction to the false accusation made by the latter absent any prior charge or indication of suspicion.

Billy does not understand the judicial complications we witness in the summary trial that sentences him to death. Yet he does at the moment of his execution seem to grasp the necessity of Captain Vere’s having ordered his hanging. Melville has the young sailor, in his dying words, bless the captain and thereby he assists Vere in his efforts to prevent mutiny.

The young sailor’s physical disability combines with his inexperience in detecting deceitful malice to all but cancel out his ability to exercise the freedom of self-command. In Melville’s portrayal of Vere, in contrast, we see the demonstration of a self-command all but complete.

“Starry Vere” Must Pass Judgment

Vere is convinced that Billy has not been engaged in seeding treason among the crew. But he delivers the death sentence because, notwithstanding Billy’s innocence of malice, simply by striking an officer the young man has caused mutiny to become imminent. The crew has become aware of a sudden secrecy among the officers, and, once they learn of Claggart’s death, they will regard clemency for his killer as evidence of their officers’ timidity owing to the Great Mutiny at the Nore. By temperament Vere would prefer delay, yet he perceives the necessity of prompt capital punishment given the circumstances. He must overcome, as well, his friendly feelings for the young sailor. Melville compares Vere’s affection for his underling with that of Abraham preparing to sacrifice his son Isaac.

Finally, he must act contrary to some of his own convictions and favored habits of conduct. Vere habitually insists upon strict adherence to established forms. He has been known to say that such regularity constitutes the very substance of social order. Yet to overcome the sympathies for mitigation that he senses in his colleagues on the martial court, Vere must resort to some management he knows is not in keeping with officially prescribed usage.

In recognition of his fondness for reading philosophic books, the captain has come to be called “Starry Vere.” But Melville now adds that in this case, his practicality should have acquired for “Starry” a new meaning—one establishing Vere as an ideal, now that of a “lode-star.” In Vere’s prudence Melville locates his norm for achieving moral freedom.

One might like to know what Melville considers the relation between the two forms of liberty that figure in Billy Budd. One way of putting the question: Of the three nations that come to sight in the story, can we infer which of them appears the best for promoting in its citizens the capacities required for attaining self-command in the degree that Vere has attained it?

Given Melville’s insistence upon human fallibility throughout his writings, it seems doubtful he would judge political constitutions, however well-devised, a sufficient or even a necessary condition for achieving moral freedom. But if one takes into account both Battle-Pieces and Billy Budd, it would appear the American Constitution provides best ground for cultivating self-mastery. Yet, one must add, for Melville this estimate would be justified only on the understanding that America’s Constitution had undergone a second birth of freedom toward the accomplishment to which Lincoln had devoted his statesmanship.