The Peculiar Institution and the Supreme Court

by Joyce Lee Malcolm

Paul Finkelman, in his new book, Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation’s Highest Court, plunges into the private lives of the three most prominent Supreme Court justices of antebellum America—John Marshall, Joseph Story, and Roger Taney—to expose their views on slavery. Finkelman’s expertise on law and slavery is both an advantage and a problem. The advantage, he knows his subject well; the problem, he is so intent on damning his three subjects that he fails to consider the compromises that produced the still-young Constitution and limited the decisions of the justices who were sworn to uphold it. There is also the oddity (injustice, really) of including Story in his denunciation.

At the root of the problem is the original Constitution. Finkelman seems to agree with the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s characterization of it as a “covenant with death” and unsparingly slams his three judicial subjects for promoting an “assault on American liberty” presumably by enforcing it. He insists the Court on which these men sat undermined earlier political compromises on slavery. That is undoubtably true of Taney’s infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857. On the other hand, Finkelman claims that instead of helping to bring an end to slavery, the three justices “invariably voted against liberty and in favor of slavery.” That conclusion is more questionable.

Let’s look at each of his justices in turn.

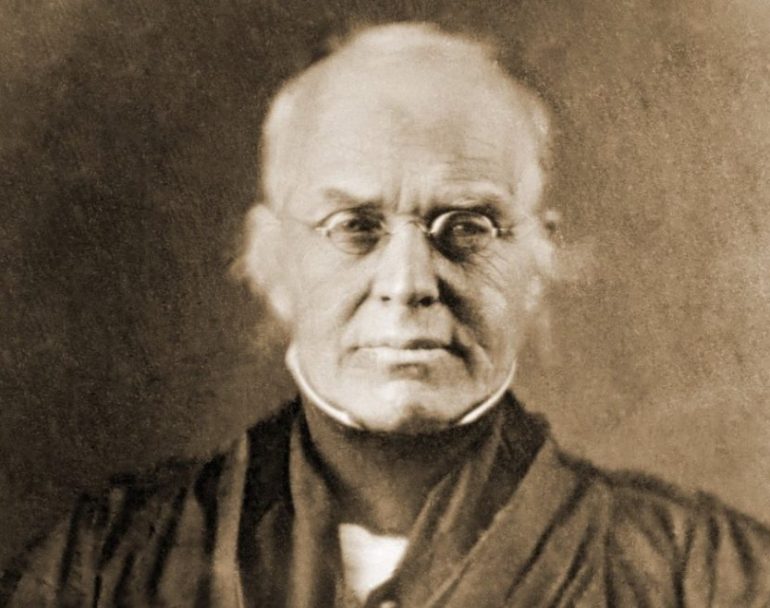

John Marshall is well known as the owner of numerous slaves. He was not opposed to slavery but was a founder and life member of the American Colonization Society in Richmond whose aim was to resettle slaves in Africa. Yet whatever his private views, Marshall was learned in the law and obliged to apply it. In the 1825 case of the French slave ship The Antelope, seized after America had banned the slave trade, Marshall distinguished between the law of nature and the law of nations. He divided the law of nations into positive law, customary observances, and general principles of right and justice, finding that the slave trade failed on all three. While adding that every man has a natural right to the fruits of his own labor and that nations, such as America, can pass laws against the slave trade, no nation, he pointed out, can impose a rule on another.

The Court’s decision set nearly all the enslaved Africans on board The Antelope free. Finkelman concedes that the Marshall Court did uphold freedom for some slaves and supported sanctions against some slave traders, but complains that Marshall left other justices to write these opinions.

As for Justice Taney, he was unquestionably pro-slavery and well deserving of the accusation of injustice. Nothing new here.

When he turns to Justice Story, Finkelman is determined to overlook Story’s anti-slavery stances. He admits that Story condemned slavery while riding circuit, “urging grand juries to vigorously investigate violations of federal laws prohibiting the African slave trade.” Story, he adds, also spoke out, although not from the bench, during the debates over the Missouri Compromise, and was adamantly against the extension of slavery into the West. In fact Finkelman refers bitterly to the Antelope case where, he argues, “Chief Justice Marshall eviscerated Story’s antislavery jurisprudence.”

None of this, however, is sufficient to exonerate Story in Finkelman’s mind. He charges Story with failing to exert his influence in slave-trade cases, and saying nothing in other cases. Story’s comments against slavery are brushed aside and he is condemned for his silence on the bench. Finkelman also notes that Story supported the fugitive slave law of 1793. “However much he disliked slavery,” Finkelman insists that Story’s “jurisprudence supported and protected the institution.” The judge is damned.

Finkelman appears guilty of projecting modern notions of judicial activism onto earlier history. Justices were not then, and are not now, meant to be “change agents” and ought not be faulted for leaving it to Congress to alter the law and to the amendment procedure to amend the Constitution. Does their ruling on the established law and a Constitution Finkelman finds (with respect to slavery) seriously unjust really make them unjust?

The author points out the places in the Constitution that deal with slavery or might apply to slavery, albeit the document carefully avoids mentioning the word. He argues that these three justices “might have showed restraint in interpreting the power of Congress to regulate slavery in the territories.” Didn’t Taney do that, although in a way that was not to Finkelman’s liking?

On the other hand, he seems to agree with Garrison that the document reeks with the aim of protecting slavery, even regarding the Electoral College as giving too much power to the South and being “deeply undemocratic.” Of course it was undemocratic. Anyone reading the debates on the drafting of the Constitution will immediately realize how fearful the Framers were of creating a democracy, a form of government history had shown to be unstable and even dangerous. They deliberately designed a republic, not a democracy. The decision to create the Electoral College was not due to a desire to perpetuate slavery but to find a safe means to elect a President giving due consideration to every state and not simply holding a direct popular election. He also complains that the amendment procedure is too difficult, and faults doctrines such as the “police powers” of the states in commerce cases and the notion of unfunded mandates as aids to perpetuate slavery.

This is an interesting book. But the author assumes Supreme Court justices ought to have followed their own predilections on the bench, not blindly interpreting a Constitution that supported slavery, and condemns them for upholding the Constitution rather than amending a document he finds seriously abusive. Abusive it was, regarding slavery; but was it the Supreme Court’s office to correct that? Of the three condemned justices charged with “injustice,” Taney did follow his own biases and preferences. The results were disastrous. After the Civil War, the Constitution would be amended in the way the Constitution mandated, to abolish slavery and protect the rights of the freed slaves.