The Plot to Undermine the Electoral College

by Ian Drake

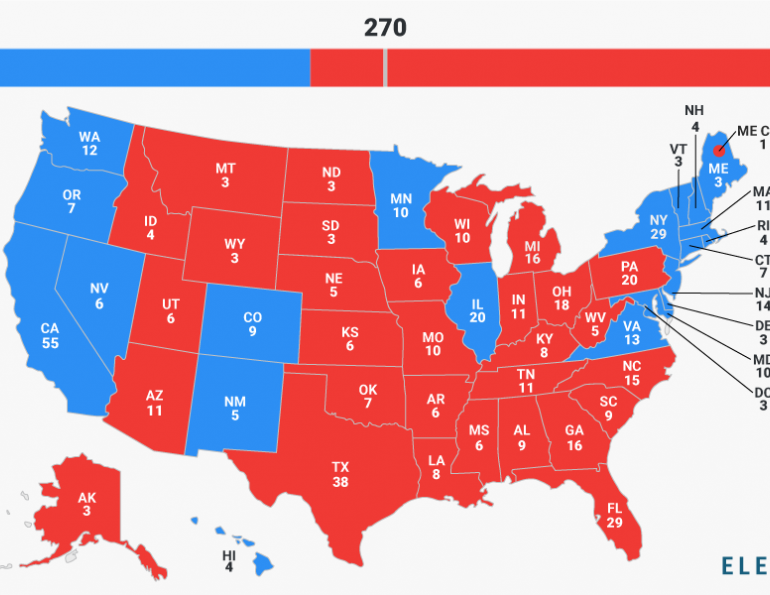

In the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton won the popular vote for president by just under three million votes. But under the Constitution’s electoral voting system, Clinton lost the election to Donald Trump by a decisive margin, with a final total of 304 to 227. Although this was only the fifth instance in United States history where the popular vote winner lost the electoral vote, it was notable because it was the second such occurrence in the last generation. In the 2000 election, Al Gore won the national popular vote by a little more than half a million votes, but famously lost the electoral vote after losing Florida’s popular vote. Prior to 2000, the last time the popular vote winner lost the electoral vote was 1888, when Grover Cleveland secured just over 90,000 more votes than Benjamin Harrison, yet lost the electoral contest.

The 2000 and 2016 election results are unusual in the longue durée of United States history, but they have come close together. Accordingly, constitutionalists should rightly be fearful of, and pay heed to, the recent calls for reform of the electoral system. One possible route to reform is the amendment process of Article V of the Constitution. This is the route most recently suggested by Rep. Steve Cohen (D-TN), who represents Tennessee’s Ninth District. On January 3, 2019, Rep. Cohen introduced H.J. Res. 7, which would abolish the electoral college and make the elections of President and Vice President decided by a national popular vote. Of course, this is hardly novel—the Electoral College has been the subject of more constitutional amendment proposals than any other constitutional provision. But enacting a constitutional amendment is very difficult. Article V requires two-thirds support in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of the states. This double-supermajority hurdle has resulted in only 27 successful amendments out of the many thousands of proposed amendments in the history of our republic. All previous proposals to alter the Electoral College have failed, with the notable exception of the Twelfth Amendment of 1804, which was enacted in response to the Adams-Jefferson election of 1800. Unsurprisingly, then, Rep. Cohen’s proposal seems to have the same chance of enactment as earlier proposals: it only has nine co-sponsors (all of whom are Democrats), there is no companion proposal in the Senate, and no action has been taken on Cohen’s bill in committee.

Although the prospects are dim for any constitutional amendment to the Electoral College system, there is an alternative route that reformers are attempting to take: an interstate compact. Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution implies that states can make agreements, or “compacts,” with one another. The specific text provides: “No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, … enter any Agreement or Compact with another State.” Interstate compacts have usually been made for non-federal purposes, such as adjusting state boundaries or forming regional interstate agreements on handling waste disposal or regional lotteries. Importantly, the Constitution’s text provides that interstate compacts must be approved by Congress, and there have been only a few instances when the Supreme Court has allowed a compact without congressional approval.

Seeking to exploit this Constitutional provision, proponents of Electoral College reform have submitted to the states the National Popular Vote (NPV) interstate compact. The NPV plan proposes to award states’ electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. In practice this means a state abiding by the NPV would award electoral votes to a national vote-winner, even if the majority within the state did not prefer that national winner. Currently, all but two states award their electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote within the state. As we shall see, this is a largely silent, invidious, and unconstitutional plan to abolish the Electoral College.

The effort is silent because it is being enacted on a state-by-state basis and has received only sporadic local media coverage, with very little national attention. Once the plan has been enacted in a number of states equal to the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency, then the NPV plan will go into effect in each enacting state. Fifteen states and the District of Columbia have enacted the plan, totaling 196 electoral votes. As of this writing, Oregon is the latest addition to the roster of states that have enacted the NPV. On June 12, 2019, Governor Kate Brown signed SB 870 into law. The remaining 74 electoral votes could be obtained if only a handful of states enact the compact.

When the Framers created the Electoral College, they thought the choice of executive would be made by a group of well-informed, prudent electors, who would be familiar with the character of those running for president. Historically, however, the Electoral College has ratified the popular vote preferences in the states, within the context of the two-party system. Nevertheless, the historical function of the Electoral College has served the nation better than the Framers envisioned. Candidates must compete on a national scale within the two-party system, often in “battleground states,” where it is uncertain how the majority in that state will vote. Battlegrounds shift over time, so each candidate must take into account the large national framework and campaign in states that would be ignored if the national popular vote were the basis for selection.

The NPV plan seeks to replace the Electoral College without amending the Constitution. NPV proponents contend no constitutional amendment is needed because the Constitution leaves the appointment of electors to the states and an interstate compact can reflect the will of the states. Although under Article II, Section 1 states can appoint electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” there is no constitutional basis for abolishing the state-based electoral system in agreement with other states. Proponents agree the plan is subject to the Compact Clause. However, they claim Congress is not required to consent to the NPV. The Supreme Court has upheld a few compacts that lacked congressional approval, but only those that do not disadvantage states that have not joined the agreement and do not interfere with federal purposes. For instance, the Court has upheld agreements on state boundaries that lacked Congress’s imprimatur. However, state boundaries or regional commissions are a far cry from altering the federal system created especially for choosing the President.

There are several legal issues that prevent the states from converting the presidential election system into a popular vote system via interstate compact. First, compacts must be submitted to Congress for approval if non-member states are disadvantaged by the compact. Under the NPV, high-population states will have an advantage over low-population states, or states that do not join the compact. For instance, a less-populated state that is competitive – that is, the state is not a “safe” state for either major party – in the presidential election would be disadvantaged by not being a member of the NPV because candidates will seek votes in high-population areas and in safer states, to the exclusion of low-population states. Under the Electoral College system, a low-population, competitive state will attract candidates because the state’s electoral votes are needed.

Second, Congress must approve any compact that interferes with the exercise of a federal function or federal authority. The Electoral College is a manifestly federal institution; it was created by the Constitution, with the objective of having the president selected within the context of the states, not the general populace. The states are not merely administrative units of the federal government; they are sub-national sovereign polities that determine how their populaces participate within a national process. Accordingly, the NPV must be submitted to Congress for approval because the NPV seeks to both advantage member states and alter an institution created in the Constitution.

Finally, the Supreme Court has held that congressional approval of an interstate compact converts the agreement between states into federal law. Under the Supremacy Clause of Article VI of the Constitution, Congress can only enact laws that are in accord with the Constitution. Congress could not enact a regular statute to convert the Electoral College into a national popular vote; a constitutional amendment is needed for that. Therefore, if Congress’s approval of any interstate compact converts the compact into federal law and Congress is required to review the NPV, then Congress cannot constitutionally approve the NPV because Congress cannot enact on its own what the NPV signatory states seek to do through an interstate compact.

Constitutionalists should not content themselves with simply reminding people that the dichotomy of winning the popular vote but losing the electoral vote has only happened five times out of the 48 elections since 1824. The two most recent times have been within the last 20 years, and constitutionalists cannot predict with certainty that more such elections will not happen more frequently in the coming years. In short, we cannot rest upon history.

As such, we must take seriously all efforts to convert the electoral vote system into a national popular vote and combat them with arguments premised not only upon history, but also upon what kind of nation we will have if the presidency is determined by a national popular vote. It would mean the demise of federalism, with states playing no effective role in the election of the president. It will mean regional candidacies, with campaigns for a national office concentrating on one region to the exclusion of all others. It will consist of contests with many candidates, representing narrow special interests, hoping to gain the barest of pluralities in order to win. (If party poohbahs fear they have only marginal control now over who is the standard bearer, they haven’t seen anything yet! The NPV could mean the demise of political parties, at least in relation to the presidency.) It will mean a further aggrandizement of the presidency in comparison to Congress, which means further erosion of what little self-government is left at the national level.

The constitutional amendment now languishing in a House committee has little chance of becoming law. But the NPV is a real and growing threat, to which most media have paid only sporadic attention. The NPV compact is a poor alternative to the Electoral College and is manifestly unconstitutional. Once it goes into effect, the only institutional hope left to constitutionalists will be the Supreme Court. Currently, that is a court that is divided five to four on controversial constitutional issues. A single justice’s vote is a thin reed upon which to hang our hopes for preserving this vital constitutional institution.