Lawsuit Update: Why I Keep Fighting

By: Mike Maharrey

Yesterday, I attended oral arguments at the Kentucky State Court of Appeals for the lawsuit the City of Lexington, Kentucky, filed against me in an effort to keep its super-secret surveillance cameras, well, super secret.

It was the continuation of a saga that has been going on for nearly two years with no end in sight. So, why do I keep fighting this?

In a nutshell, privacy matters.

First a little background.

In the summer of 2017, I filed an open records request with the Lexington Police Department seeking information on surveillance technology that it owns or operates. I was told the LPD has 29 “mobile surveillance cameras,” but the city refused to divulge any information about them. I appealed the city’s decision to release the records to the attorney general’s office in an opinion issued in September 2017, the AG ruled in my favor and ordered the release of all information on these cameras. Instead of turning the records over to me, the city filed a lawsuit against me in October 2017.

Over the next year, a circuit court judge ruled in my favor not once, but twice. Still, the city refused to relent, so now the case has moved to the appellate court level.

In a nutshell, the police claim that if I know what kind of cameras they have, it will jeopardize “officer safety” and put an undue burden on the city because it will have to buy new cameras once the secret comes out. The circuit court judge ruled that the city did not meet its burden of proof on either grounds.

But during the lower court hearing, the judge denied a motion for an “in camera review.” This would involve the city presenting evidence to the judge in secret so he can better determine if the information should remain, well, secret — out of the public domain.

But in their questions to the attorneys during oral arguments, the issue of how much latitude government agencies should have when it comes to keeping surveillance equipment secret did come up. In fact, the city attorney for Lexington implied that I must be a criminal because, in his view, there is no other reason to want specific information on police department spy-gear.

One of the judges seemed to think police should be able to keep pretty much everything secret if they assert that it should be secret, and we should just trust their word. Luckily, the judges really can’t rule based on their opinion about surveillance during appeal — at least they’re not supposed to. They are bound by the facts of the case present at the lower level, and matters of procedural law. But the judge’s comments were revealing.

The head of the panel seemed more sympathetic to my position. She poked a little fun at the city attorney’s assertion that drug dealers are savvy enough to use my open records info to thwart police. He doubled down, actually saying that if this precedent is set, and the LPD has to reveal information about its surveillance technology, criminals will start doing open records requests to learn about surveillance technology. I resisted the impulse to laugh out loud.

The entire discussion about my reasons for wanting access to this information magnifies my biggest frustration about this case and the reason I continue to fight the city.

A lot of people, including at least one of the judges, don’t seem to understand the inherent threat to our fundamental right to privacy posed by modern surveillance technology.

Our right to privacy logically flows from the principle of self-ownership. If we own ourselves, we have a natural right to keep any aspect of our lives out of public view, to shield any thought or action from the scrutiny of others. The government must meet an extremely high threshold in order to infringe on this fundamental right. That’s why both the U.S. and every state constitution feature provisions prohibiting government invasions of an individual’s privacy with few exceptions, and even then, with strict limits.

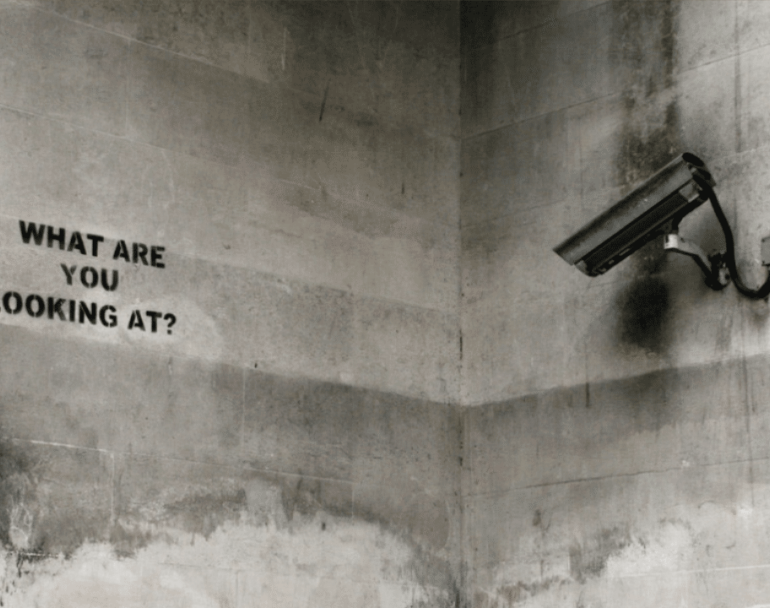

Using modern surveillance technology, government agents can gain access to the most intimate details of our lives without us even knowing it.

On the one hand, surveillance provides a great tool for fighting crime. But with it comes an incredible potential for abuse. Given the risks posed to our most fundamental civil liberties, this kind of technology should only be used with oversight and transparency. The community has a right to know what kinds of surveillance tools police use. It has a right to expect that police and other government agencies put policies and procedures in place to ensure oversight and transparency of surveillance programs, to protect collected data, to prevent sharing of such data and to ensure the protection of privacy rights. And communities even have a right to say, “You know, we think the potential risks outweigh the rewards when it comes to a specific technology.”

None of this is possible when can police obtain and use surveillance technology in complete secrecy.

That’s why I want this information. I want to know how, when, why and where police deploy their spy gear. And I want to give the community a voice in determining what level of surveillance they will accept. This remains impossible if police can operate behind a veil of secrecy.

In a nutshell, I want oversight and transparency. And no — I won’t defer to the police to decide. I don’t trust them. Government agencies determining the extent of their own power has never ended well.

Patrick Henry perhaps put it best:

“The liberties of a people never were, nor ever will be, The liberties of a people never were, nor ever will be, secure, when the transactions of their rulers may be concealed from them. The most iniquitous plots may be carried on against their liberty and happiness.”