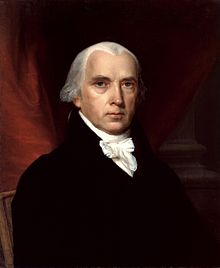

A Christmas Gift from James Madison: The Virginia Resolutions of 1798

Mike Maharrey

Resolutions drafted by James Madison and passed by Virginia on Dec 21. and 24, 1798, answer a timeless question: What do we do when the federal government oversteps its constitutional bounds?

All too often, we simply ignore it. But James Madison had other ideas. The man known as “The Father of the Constitution” insisted states are “duty bound, to interpose” and arrest “the progress of the evil.”

Madison made this emphatic statement in the Virginia Resolutions of 1798, a document he drafted in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Within a decade of the ratification of the Constitution, the federal government was already testing the limits of its authority. During the summer of 1798, Congress passed, and President John Adams signed into law, four acts together known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. With winds of war blowing across the Atlantic, the Federalist Party majority wrote the laws to prevent “seditious” acts from weakening the U.S. government. Federalists utilized fear of the French to stir up support for these draconian laws, expanding federal power, concentrating authority in the executive branch and severely restricting freedom of speech.

Two of the Alien Acts gave the president the power to declare foreign U.S. residents an enemy, lock them up and deport them. These acts vested judicial authority in the executive branch and obliterated due process. The Sedition Act essentially outlawed criticizing the federal government – a clear violation of the First Amendment.

Recognizing the grave danger these act posed to the basic constitutional structure, Thomas Jefferson and Madison drafted resolutions that were passed by the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures in Nov. and Dec., 1798, respectively. The “Principles of ’98” formalized the principles of nullification as the rightful remedy when the federal government oversteps its authority.

After Gov. Garrard signed the Kentucky Resolutions on Nov. 16, Jefferson sent a draft to Madison, writing, “I inclose you a copy of the draught of the Kentuckey resolves. I think we should distinctly affirm all the important principles they contain, so as to hold to that ground in future, and leave the matter in such a train as that we may not be committed absolutely to push the matter to extremities, & yet may be free to push as far as events will render prudent.”

Madison did just that, drafting his own resolutions for introduction in the Virginia legislature. The Virginia Resolutions of 1798 declared the Alien and Sedition Acts “unconstitutional.” Madison also asserted that the states had an obligation to act against egregious federal exercises of undelegated power.

“That this Assembly doth explicitly and peremptorily declare, that it views the powers of the federal government, as resulting from the compact, to which the states are parties; as limited by the plain sense and intention of the instrument constituting the compact; as no further valid that they are authorized by the grants enumerated in that compact; and that in case of a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of other powers, not granted by the said compact, the states who are parties thereto, have the right, and are in duty bound, to interpose for arresting the progress of the evil, and for maintaining within their respective limits, the authorities, rights and liberties appertaining to them.”

Madison gave his draft of the Virginia Resolutions to Wilson Cary Nicholas, who showed them to Jefferson. In a letter dated November 29, 1798, Jefferson recommended adding more emphatic language in declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional.

“The more I have reflected on the phrase in the paper you shewed me, the more strongly I think it should be altered. suppose you were to instead of the invitation to cooperate in the annulment of the acts, to make it an invitation: ‘to concur with this commonwealth in declaring, as it does hereby declare, that the said acts are, and were ab initio—null, void and of no force, or effect’ I should like it better. health happiness & Adieu.”

Nicholas added words declaring that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional “not law, but utterly null, void and of no force or effect.”

John Taylor of Caroline introduced Madison’s resolutions with Nicholas’ addition on Dec. 10, 1798. He described the resolutions, “as a rejection of the false choice between timidity and civil war.” Taylor argued that state nullification provided an alternative to popular nullification – in other words outright armed rebellion. In legislative debates, he argued that “the will of the people was better expressed through organized bodies dependent on that will, than by tumultuous meetings; that thus the preservation of peace and good order would be more secure.” [1]

In the course of the debate, Jefferson’s suggested wording was removed. During the period following passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, there was talk of outright revolution. Both the Kentucky and Virginia legislatures went to great pains to ensure they were striking a balance between a hard line and moderation. They wanted to make their point, but they did not want to spark violence.

Removing Jefferson’s wording did not change the substance of the resolutions. In fact, declaring a law “unconstitutional” was essentially the same as calling it “null, void and of no effect.” Alexander Hamilton inferred this distinction during the New York ratification debate.

“The acts of the United States, therefore, will be absolutely obligatory as to all the proper objects and powers of the general government…but the laws of Congress are restricted to a certain sphere, and when they depart from this sphere, they are no longer supreme or binding.”

The Virginia House of Delegates passed the resolutions on Dec. 21, 1798, by a vote of 100 to 63. The Senate followed suit on Dec. 24, by a 14 to 3 margin.

Taken together, the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions lay out the principles of nullification. But they did not actually nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts. These non-binding resolutions merely made the case and set the stage for further action.

Correspondence between Jefferson and Madison indicate they didn’t plan to stop with the resolutions. They hoped to use them as a springboard for state action against the unconstitutional Alien and Sedition Acts.

NOTE

[1] Robert H. Churchill, Manly Firmness, the Duty of Resistance, and the Search for a Middle Way: Democratic Republicans Confront the Alien and Sedition Acts, (1999 Annual Meeting of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, Lexington, Ky., July 17, 1999) (http://uhaweb.hartford.edu/CHURCHILL/SHEAR_Paper.pdf)