The Legend of the Proslavery Constitution

by Jason Ross – Law & Liberty

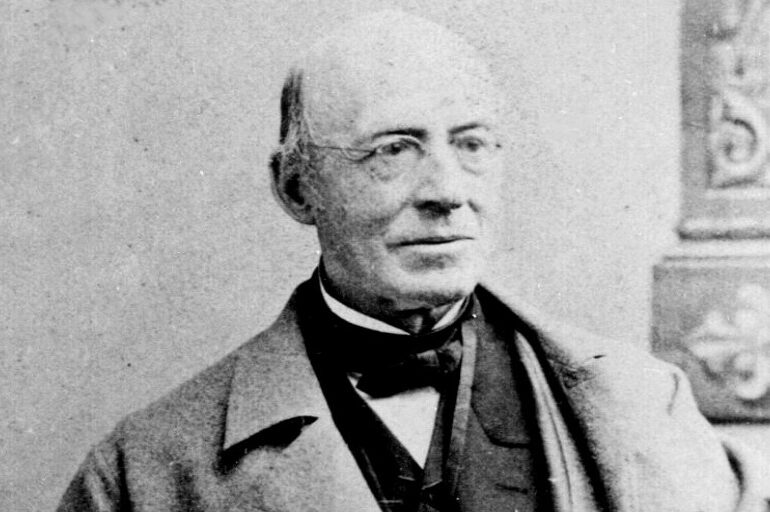

Historians today speak of the “proslavery Constitution” and “antislavery constitutionalism”; they almost never speak of the “antislavery Constitution” or of “proslavery constitutionalism.” This fact is a testament to the profound success of the critique of the Constitution leveled by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. In his condemnation of the Constitution as proslavery, his resort to Madison’s “Notes from the Constitutional Convention” to demonstrate this case, and his rejection of the Constitution’s authority—all punctuated by his dramatic burning of that document during a Fourth of July address—Garrison has set the terms within which subsequent historical debate on the relationship between the Constitution and slavery has been carried out.

Even historians who disdain Garrison’s caustic critique of the Constitution, who question his partial readings of the Convention’s debates, and who emphasize the development of constitutional arguments that culminated in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments concede at some level Garrison’s premise that the Constitution was intended to be proslavery. Thus, it is sad, but not surprising, to see that the mob rounded up by the New York Times’s “1619 Project” is setting fire to the project of antislavery constitutionalism. Garrison’s belief that the Constitution was intended to be proslavery is an unquenchable fire that will eventually consume all it touches.

It would be one thing if Garrison’s argument was spreading like wildfire because it was true. Instead, his interpretation (and condemnation) of the Constitution continues to spread because it is a legend—a tale that continues to be repeated, without examination, because the story feels too satisfying for it not to be true.

Madison’s “Notes” and Garrison’s Change of Heart

Historians have known since well before Max Farrand set out to write the definitive history of the formation of the Constitution a century ago that “the great source of our information as to what actually took place in the Federal Convention, the Madison Papers, first appeared in 1840 . . . just the time when the slavery question was becoming the all-absorbing topic in our national life.” Though Farrand merely noted this as a coincidence, the New Left historian Staughton Lynd read causation into this coincidence, claiming that Garrison and his followers seized on James Madison’s “Notes” “to show in detail what they had long suspected: that the revered Constitution was a sordid sectional compromise, in Garrison’s words ‘a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.’” This coincidence has been treated as a cause so many times since that historians now take as self-evident the conclusion that Garrison and his followers innocently consulted Madison’s Convention notes only to discover a secret sectional bargain so sinful as to require the Constitution to be set ablaze and the Union to be torn asunder.

This story is compelling, but it is not true. In fact, the truth is almost exactly the opposite. As I have detailed at length, Garrison, during the early part of his abolitionist career, supported the project of advancing constitutional arguments against slavery. Indeed, several states had passed personal liberty laws to protect the due process and habeas corpus rights of those accused of having escaped from servitude, and Garrison took heart in an 1836 ruling by the New Jersey Supreme Court that upheld one such law, holding that the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 unconstitutionally regulated the arrest of fugitive slaves. He wrote to his business partner, Isaac Knapp, to say that he wished his fellow abolitionists “would assume the ground maintained recently by Judge Hornblower of New Jersey.” Garrison also said he would “go further, and maintain, (all previous constructions to the contrary notwithstanding,) that by the Constitution of the U.S., as well as by that of our own State, no slavery can lawfully exist in this country.” Co-founder of the New England Anti-Slavery Society Ellis Gray Loring confirmed in 1838 that “influential persons (Mr. Garrison among them), think slavery unconstitutional, and believe it would be so pronounced by the Supreme Court of the United States if the point should ever be made.”

Garrison’s faith in a constitutional solution to slavery was shattered by the Supreme Court’s notorious ruling in Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842). The decision invalidated state personal liberty laws and asserted that the Constitution protected the private right of recaption by which slaveowners could seize those whom they alleged had escaped from service. Garrison was livid with the decision, and rightly so. But in his anger, he threw up his hands and conceded that the Taney Court’s interpretation of the Constitution was true and irresistible. The Constitution,

is not a ball of clay to be moulded into any shape that party contrivance or caprice may choose it to assume. It is not a form of words, to be interpreted in any manner, or to any extent, or for the accomplishment of any purpose, that individuals in office under it may determine. It means precisely what those who framed and adopted it meant—NOTHING MORE, NOTHING LESS, as a matter of bargain and compromise. Even if it can be construed to mean something else, without violence to its language, such construction is not to be tolerated against the wishes of either party. No just or honest use of it can be made, in opposition to the plain intention of its framers, except to declare the contract at an end.

Not all abolitionists agreed with Garrison in condemning the Constitution as proslavery. In the first book-length argument that the Constitution was antislavery (published just before the Prigg decision), George Washington Mellen had access for the first time, through Madison’s “Notes,” to the drafting history of the fugitive slave clause. He learned that a motion by the South Carolina delegates Butler and Pinckney “that fugitive slaves and servants be delivered up like criminals” had been rejected; the phrase “fugitive slaves and servants” was replaced by “any person bound to service or labor in any of the United States.” Further, the phrase “delivered up like criminals” was replaced with “delivered up to the person justly claiming their service or labor.” That latter language, Mellen noted, was then further altered to remove reference to the justice of claims of servitude, and to call for persons in question to be delivered “on claim of the party to whom such labor or service may be due.” The thrust of this drafting history, newly revealed to Mellen by Madison’s “Notes,” was that the fugitive slave clause should be understood to mean that “no man should be given up, unless the debt of service or labor is proved.”

Though the Taney Court claimed fidelity to the intent of the framers, they paid no attention to the framers’ words.

Following Prigg, and Garrison’s acceptance of the Taney Court’s construction of the Constitution as proslavery, Liberty Party cofounder Gerrit Smith circulated a letter calling the Constitution a “noble and beautiful Temple of Liberty,” and arguing that there were merely “pro-slavery exceptions” to the Constitution’s “reigning anti-slavery principles.” He also relied on Madison’s “Notes” to refute the Court’s construction of the fugitive slave clause, and concluded more broadly,

Who can read the “Madison Papers,” and in other ways also acquaint himself with the mind of the Convention which framed the Constitution, and yet believe that the Constitution would have suffered it? Who can believe that this Convention, which would not suffer the word “slave,” or the word “slavery,” or even the word “servitude,” to have a place in the Constitution; which agreed with its Mr. Gerry, that it “ought to be careful not to give any sanction to slavery;” and which, to use the very words of its leading member, Mr. Madison, on the floor of the Convention, “thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in man”—who, I say can believe that this Convention would have consented to let the Constitution declare in plain, unequivocal terms, the right of the slaveholder to chase down, and to chase down unhindered, the poor innocent fugitive from slavery?

Though Garrison was aware of Madison’s “Notes,” there is no historical evidence of Garrison having cited or otherwise engaged with them before he responded to Smith’s letter. His earlier references to the Constitution’s formation came from notes taken at the Convention by Robert Yates, from Luther Martin’s “The Genuine Information,” and from Jonathan Elliot’s Debates in the Several State Conventions. After Smith introduced Madison’s “Notes” in defense of the antislavery Constitution, however, Garrison made it his pet project to publish “such extracts from ‘THE MADISON PAPERS’ as relate to the guilty compromise that was made at the formation of the Constitution”—and nothing more from them. In this way he sought to impugn the broader strategy of articulating an antislavery construction of the Constitution, running nine editorials for this purpose over the next two months.

The Antislavery Constitution

Rather than being the cause of Garrison’s condemnation of the Constitution as proslavery, then, Madison’s “Notes” were a casualty of it. Ever since Garrison sought to undermine them as part of his battle to end the project of antislavery constitutionalism, they have been viewed in light of Garrison’s sinister accusations against them. It did not need to be so. Indeed, Madison’s “Notes” were an important part of the argument made by the counsel for the state of Pennsylvania, Thomas Hambly, in Prigg. In his brief to the Court, Hambly insisted that the due process of law was the core principle of the Constitution, and warned that if “one can arrest and carry away a free man ‘without due process of law’… your Constitution is a waxen tablet, a writing in the sand; and instead of being, as is supposed, the freest country on earth, this is the vilest despotism which can be imagined!” The “spirit” of the Constitution as Hambly saw it was against the establishment of such a power, and Hambly cautioned, “The same power that can upon simple allegation seize and carry off a slave, can on the allegation of service due, seize and carry off a free man.” Instead, he held that the text of the fugitive slave clause emphasizing a “claim” implied a legal procedure, rather than any asserted right of recaption.

Turning to Madison’s “Notes,” Hambly argued that any legal procedures regarding the recovery of fugitive slaves were expected to be left to state legislation. Hambly noted the drafting history of the fugitive slave clause and observed that its alteration was motivated, in part, to avoid the insinuation that the national government would be responsible for its enforcement and to avoid the suggestion that slavery was “‘legal’ in a moral view.” In Hambly’s view, Madison’s “Notes” demonstrated that the framers did not intend the federal government to have any power or jurisdiction to adjudicate issues related to laws that states had made concerning slavery. The “question of legally or justly held was to be tried in the States, and the manner thereof be pointed out by State legislation, excepting only it could not discharge the fugitive from service.”

Though the Taney Court claimed fidelity to the intent of the framers, they paid no attention to the framers’ words, cited in Pennsylvania’s argument, from Madison’s “Notes.”

Madison’s “Notes” became a casualty of Garrison’s unparalleled rhetorical firepower, but they had been well on their way to becoming a catalyst for constructions of the Constitution as antislavery. Perhaps they arrived a generation too late to combat the proslavery constitutional arguments that the Supreme Court endorsed in Prigg and that Garrison reluctantly accepted as irresistible. But if we now know that Garrison’s legendary critique of the Constitution is really just a critique of the Constitution as interpreted by the Taney Court circa 1842, it is time for us to set Garrison’s inflammatory argument aside. Rather than approaching our nation’s founding from the perspective of Garrison’s critique of the Taney Court’s discredited interpretation, let us once again approach our Constitution in light of the antislavery construction developed by the interpreters of Madison’s “Notes” who preceded Garrison, and that has been given to it over time by the deliberate sense of our national community.

Jason Ross is an Associate Professor at Liberty University. He is currently at work (with Gordon Lloyd) on Slavery and the Well Constructed Union: Use, Misuse, and Neglect of “The Madison Papers”.