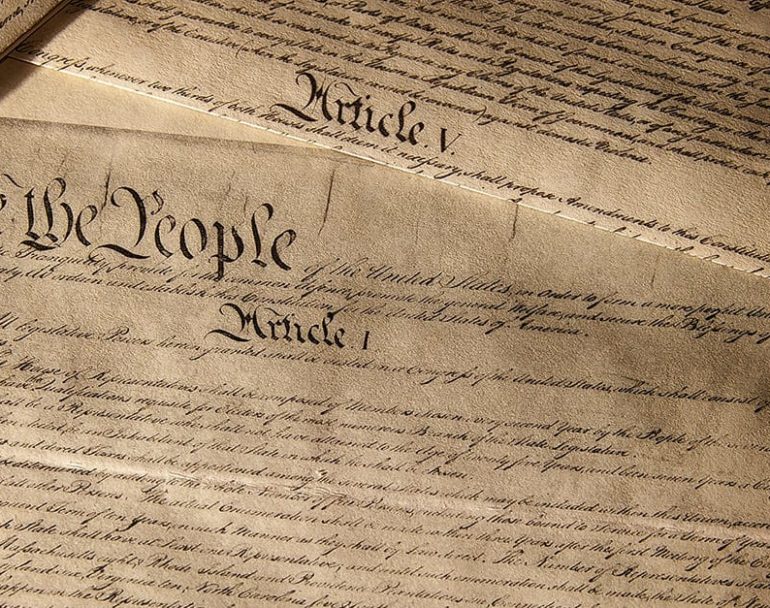

What Is Originalism?

By: Rob Natelson

When President Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, it was widely claimed he was appointing “originalists.”

What is an originalist? Although originalists disagree among themselves over some details, they share one core belief: The courts should read the U.S. Constitution much the same way they read other documents. Judges should not create special exceptions to accommodate politicians or favored groups.

The standard rules for interpreting legal documents—often called “canons of construction”—are centuries old. Some date as far back as the Roman Empire. Originalism is how the Founders expected the Constitution to be interpreted. If you examine the Federalist Papers, you’ll find occasional references to the canons of construction.

Most of the canons are designed to serve one fundamental principle: They help us understand a document the same way the document’s creators understood it.

This basic principle applies to almost all documents. For example, suppose your spouse sends you to the grocery store with a shopping list. The list tells you to buy vegetables. In reading it you interpret the word “vegetables” as your spouse would have. You don’t “re-interpret” the word to mean “chocolate cake.” You remain faithful to your spouse’s intent even if you wish he or she had written “chocolate cake” instead.

Or consider the rules of a game. In baseball, you construe the rules for what they were designed to be. You read “three strikes” to mean just that. You don’t get five strikes just because you disagree with the three strike rule—or because you happen to be the batter.

This is basic honesty. For 150 years after the Constitution was adopted the judges shared a commitment to honesty in constitutional interpretation. When confronted with a phrase of uncertain meaning, they looked to the circumstances under which the phrase was adopted. They tried to recreate the understanding of those who wrote and ratified the Constitution. Yes, they sometimes made mistakes. But most of their decisions were defensible.

During the late 1930s and early 1940s, however, the government faced pressures from economic depression and World War II. Congress and the president frequently adopted measures the Constitution places outside their authority. At first, the Supreme Court tried to accommodate the government to the extent the Constitution permitted. But by the early 1940s the bench had become dominated by justices with little prior judicial experience. They changed the constitutional rules to permit Congress and the president to do things the Constitution actually forbids.

For example, the Constitution divides responsibility for regulating the economy between the states and the federal government. By the end of 1942 the court had granted almost all power over the economy to the federal government.

Similarly, the Constitution generally forbids the president from locking up people on U.S. territory without trial or access to the writ of habeas corpus. But in 1944 the court approved President Franklin Roosevelt’s order herding over 100,000 American citizens of Japanese descent into concentration camps, without trial or possibility of release. The court’s excuse was “pressing public necessity.”

In subsequent years, the court has used the same rationale—now often mislabeled the “strict scrutiny” test—to allow officials to curtail other constitutional rights. And the court has compounded these mistakes by expanding some rights beyond their constitutional scope.

The court has “re-interpreted” constitutional phrases to mean things they never meant before. Some of the results are ludicrous. For example, when the phrase “due process of law” was inserted in the Constitution it meant this: If the government proceeds against you, the government has to follow existing law in doing so. It cannot make up new rules retroactively. But in 1973, the Supreme Court “reinterpreted” the phrase to mean that states could not ban abortion!

Of course, you may agree that the states should permit abortion. But that’s not the point. An originalist believes what is important in a particular case is not what you or I think the law should say, but what it actually does say. If we disagree with a law, we can change it. If we disagree with part of the Constitution we can amend it. Having the courts unilaterally re-write the rules defies both democracy and legal fundamentals.

Fortunately, the courts still interpret most of the Constitution in a matter faithful to its true meaning. The damage has been principally in the following areas:

* The courts have expanded Congress’s Commerce Power—which was originally designed to cover trade and a few allied areas—into a power to control almost the entire economy. The courts have expanded it further to enable Congress to pass many criminal laws in areas the Constitution reserves to the states.

* They have expanded Congress’s Taxation Power to allow Congress to spend any amount it wants on almost anything it wants. That is why the government almost always runs a deficit and is more than $21 trillion in debt.

* They have expanded the federal government’s power to own land for certain purposes into a power to own land for any purpose. Today the federal government holds title to nearly 30 percent of the country and about 50 percent of the West. The raging wildfires you hear about in the West are largely due to federal mismanagement.

* The courts have used the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause and its Due Process Clauses to re-write state and federal social policy—often in direct defiance of the popular will. In some cases, the courts have even ordered states to provide subsidies or other benefits to groups the judges favor!

Will the appointment of Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh change this? Probably not. Today the only consistent originalist on the Supreme Court is Justice Clarence Thomas. A case decided last year showed that while Justice Gorsuch may have originalist sympathies, he is not as consistent as Thomas. And Justice Kavanaugh’s background suggests he may be more interested in preventing further abuses than in correcting earlier mistakes.