Separation of Powers Act Introduced in U.S. Senate

The Separation of Powers Act stops bureaucrats from dictating to judges how to interpret laws passed by Congress and their own regulations.

WASHINGTON – Republican U.S. Sens. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, Ben Sasse of Nebraska, James Lankford of Oklahoma, Thom Tillis of North Carolina, Josh Hawley of Missouri, Mike Crapo of Idaho, John Cornyn of Texas, Mike Lee of Utah, Michael Rounds of South Dakota and Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma introduced the Separation of Powers Restoration Act of 2019 on Wednesday afternoon. Companion legislation was introduced by U.S. Rep. John Ratcliffe, R-Texas, in the House. The legislation stops bureaucrats from dictating to judges how to interpret laws passed by Congress and their own regulations.

“For years, unelected bureaucrats have relied on judicial deference to expand their own authority beyond what Congress ever intended,” Grassley said. “This has weakened our system of checks and balances and created a recipe for regulatory overreach. The Constitution’s separation of powers makes clear that it is the responsibility of Congress, as the People’s representative, to make the law. And it’s the job of the courts – not the bureaucracy – to interpret the law. This bill helps to reassert those clear lines between the branches. By doing so, it makes the government more accountable to the People and takes a strong step toward reining in the regulators in any administration.”

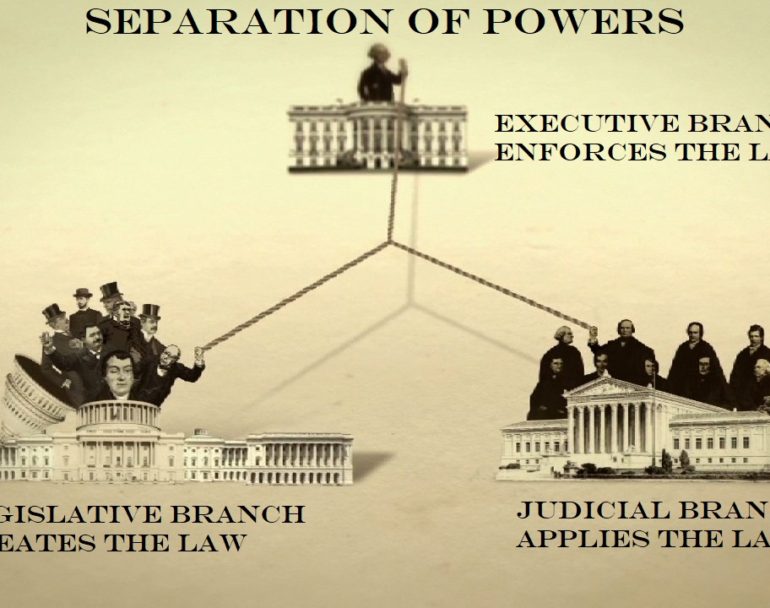

“This bill is about Schoolhouse Rock basics,” Sasse said. “Congress writes the laws, the Executive Branch enforces them, and the courts resolve cases and controversies. That basic system has been turned upside-down: Unelected bureaucrats that nobody can fire write an avalanche of regulations, and the courts just trust them to interpret the limits of the law and even their own regulations. This bill tries to restore some accountability by making sure that judges don’t automatically defer to Washington’s alphabet soup of bureaucracies.”

“The regulatory state in our country has spiraled out of control,” Ratcliffe said. “By usurping the constitutional powers granted to the Judicial Branch, unelected bureaucrats have effectively formulated their own ‘Fourth Branch’ of government, implementing countless rules and regulations – that hold the force of law – without accountability to the American people. This problem has gotten worse over the past few decades thanks to the current precedent that courts should, in many cases, defer to agencies’ interpretation of federal laws and even the regulations that they author, if deemed ‘ambiguous.’ I’m proud to be working with my Senate colleagues to overturn the court cases that are allowing this to continue, so we can restore the proper separation of powers set forth by the Constitution.”

BACKROUND:

Under the Supreme Court’s holding in Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, courts must defer to an administrative agency’s interpretation of a statute so long as the statute is “ambiguous” and the agency’s reading is “permissible.” This has been commonly known as Chevron deference. Similarly, under so-called Auer (or Seminole Rock) deference, “the ultimate criterion” for courts’ interpretation of ambiguous regulation “is the administrative interpretation, which becomes of controlling weight unless it is plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.” These criteria are incredibly vague and often interpreted quite expansively.

This represents the judiciary’s abdication of its proper role under the Constitution, giving agencies the power to stretch their authorities well beyond what Congress (and the agencies themselves) established and undermining a central purpose of the Constitution. The end result for the regulated public is more heavy-handed regulation, less predictability, and dimmed hopes for meaningful agency accountability to the law.

The Separation of Powers Restoration Act amends the Administrative Procedure Act to require that courts must decide for themselves “all relevant questions of law, including the interpretation of constitutional and statutory provisions, and rules made by agencies.” The bill further establishes that if “the reviewing court determines that a statutory or regulatory provision relevant to its decision contains a gap or ambiguity, the court shall not interpret that gap or ambiguity as an implicit delegation to the agency of legislative rule making authority and shall not rely on such gap or ambiguity as a justification either for interpreting agency authority expansively or for deferring to the agency’s interpretation on the question of law.”

This bill passed the House of Representatives in 2017 with bipartisan support by a margin of 238 to 183 as Title II of H.R. 5.

On Wednesday, March 27, 2019, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Kisor v. Wilkie on whether the Auer case should be overruled. Numerous Supreme Court justices have criticized aspects of these deference doctrines:

-Justice Scalia: “[F]or no good reason, we have been giving agencies the authority to say what their rules mean, under the harmless-sounding banner of ‘defer[ring] to an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations.’”

-Justice Thomas: “[Seminole Rock] undermines our obligation to provide a judicial check on the other branches, and it subjects regulated parties to precisely the abuses that the Framers sought to prevent.”

-Justice Gorsuch: “Chevron seems no less than a judge-made doctrine for the abdication of the judicial duty. . . . Transferring the job of saying what the law is from the judiciary to the executive unsurprisingly invites the very sort of due process (fair notice) and equal protection concerns the framers knew would arise if the political branches intruded on judicial functions.”

-Justice Kavanaugh: “In many ways, Chevron is nothing more than a judicially orchestrated shift of power from Congress to the Executive Branch.” “[T]he Chevron doctrine encourages agency aggressiveness on a large scale. Under the guise of ambiguity, agencies can stretch the meaning of statutes enacted by Congress to accommodate their preferred policy outcomes.”