Today in History: The Missouri Compromise Signed into Law

By: Dave Benner

Today in 1820, a set of bills that came to be known as the “Missouri Compromise” were signed into law by President James Monroe.

Initially seen as a gesture of conciliation between factions that would avert discord, the event generated divisive uproar and ripped asunder any semblance of national unity. The controversy, based on the question of Missouri’s statehood, ignited a national debate over the expansion of slavery, the bounds of constitutional authority, and the federal orientation of the union.

Louisiana, the first state to be carved out of the territory acquired through the Louisiana Purchase, entered the union as a slave state in 1812 with an enabling act that admitted the state to the union “upon the same footing with the original states.” The region was then renamed the “Missouri Territory.” By 1818, the renamed Missouri territory started accumulating settlers from the east, many of which travelled from the mid-South. Given the precedent set by Louisiana, many thought the state’s admission to the union would be a conventional affair. It hardly was.

Before Missouri even drew up a constitution and applied for statehood, Congress had made several attempts to impose slavery ultimatums upon the prospective state. In early 1819, a movement within the House of Representatives suggested an amendment that would prohibit slavery in Missouri and freed all slaves born to slave parents after Missouri’s admission at the age of 25. Supporting this amendment was John W. Taylor of New York, who contended that the Constitution allowed Congress to restrict slavery in the territories. He insisted that “the exercise of this power, until now, has never been questioned.”

This alone produced a spirited debate, as many within Congress denied the power to impose ultimatums on statehood on the grounds that the Constitution called only for an up or down vote on state admissions. Sometimes called “anti-restrictionists,” this group included representatives Philip P. Barbour, John Tyler, senators Nathaniel Macon and James Barbour, and Missouri’s independent ambassador John Scott.

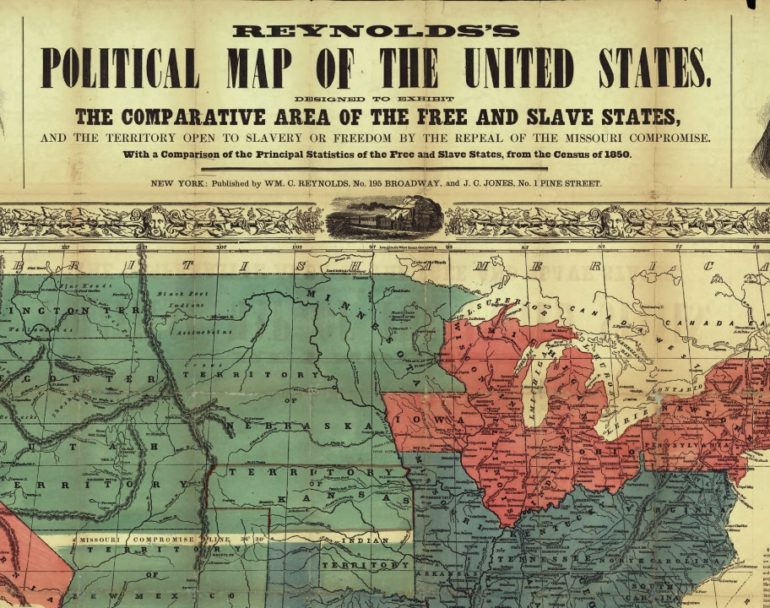

While the proposed amendment was agreeable to the House of Representatives, the plan failed in the Senate. The next year, the House passed a new plan that allowed Missouri to adopt a constitution that permitted slavery. The Senate approved such a plan, but added a provision for a geographical line to be drawn along on the southern border of Missouri at the 36°30′ parallel that extended westward. North of the line, slavery would be prohibited from all of the western territory.

At the same time as the Missouri matter was debated, the northern portion of Massachusetts petitioned to secede from the rest of the state and apply for statehood as the new independent state of Maine. In order to secure a compromise between opposing factions, the Senate also made an attempt to connect the admission bills of Missouri and Maine together. A rules resolution prevented this from happening, and the two bills were split into separate questions.

After the intense political battle in the Congress, Missouri was added to the union as a state with a Constitution that allowed slavery, and Maine entered the union as a state that prohibited slavery. Additionally, Congress agreed to adopt the proposed parallel of divide that separated slave territories from free territories. This settlement has often been called the “Missouri Compromise,” to which “The Great Compromiser” Henry Clay has been given much credit. In reality the actual results demonstrated that little compromise ever took place, and the voting on each bill reflected marked sectional divide.

The bill that enabled Missouri to draw up a pro-slavery Constitution also admitted it to the union “on an equal footing with the original states, in all respects whatsoever.” Missouri’s enabling act also required the new state to transmit a copy of the constitution it created to the government to fulfill a notification requirement. However, the act also made clear that the state’s admission of the union was not contingent upon whether Congress found the constitution to be agreeable – according to the law, Missouri would be admitted regardless.

The people of Missouri produced their own republican constitution by the middle of 1820, which expressed a desire to establish “a free and independent republic.” Therein, Article III, Section 26 prevented the state government from emancipating slaves without the consent of their owners. Just when political commotion over the state appeared to subside, a second crisis broke out when Missouri’s constitution also included an anti-vagrancy clause that prevented the migration of free blacks and mulattoes. Although this again jeopardized Missouri’s admission to the union for a time, the situation was allayed when Missouri affirmed the constitutional guarantee of privileges and immunities of the several states.

The Missouri crisis was the starting point for what became the most divisive national political issue of the 19th century – the question of whether the Constitution allowed Congress to regulate slavery in the American territories. On this question, two incongruent constitutional perspectives emerged during the “Era of Good Feelings.”

Northerners tended to argue Congress held this power through Article IV, Section 3, which provided that the legislature could make “rules and regulations” in the territories. Some also cited the precedent found in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, where the Confederation Congress prohibited slavery in the region. Article 6 of the ordinance held that there “shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” in the territory, but also included a fugitive slave clause that required the return of runaway slaves. If Congress held plenary power to make rules and regulations in the territories, this view espoused that such a power extended to the authority to eliminate slavery in the territories. During the Missouri crisis this view was promoted by Senator Rufus King, who had helped draft the United States Constitution in Philadelphia.

On the other hand, the southern perspective, denying that Congress could regulate slavery in the territories, relied upon the existence of the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. The clause prohibited the government from seizing the property of individuals “without due process of law.” This outlook held that no enumerated power, whether applicable to the states or the territories, could supersede explicit, overarching limitations that applied to the entire scope of the federal government’s power. If slaveholders chose to bring their slaves into the territories, this position rejected the notion that the general government could prevent it through the rules and regulations provision. Adhering to this view was Alexander Smyth of Virginia, who during the Missouri debates cited the Fifth Amendment as an obligatory limitation of the federal government’s authority.

These two irreconcilable doctrines produced a volley of tensions that plunged the next four decades into political strife. The situation in Missouri, for the first time, demonstrated the extent to which geographical factions apprehended the balance of power between regions that sanctioned slavery and those that did not. If Congress could systematically dictate whether states carved out of the territories could prohibit slavery, many feared that nothing would stop it from regulating the practice in the territories, which did not hold the same sovereign stature as states. The antithetical perspective, on the other hand, asserted that if Congress could not regulate slavery in the territories, that future states created from those districts would inevitably be friendly to slavery.

Besides the vitriol resulting from questions of slavery’s expansion, the situation in Missouri brought about significant questions surrounding the primacy of the states and federal orientation of the union. For his part, former president Thomas Jefferson perceived the Missouri Compromise as a calamity. Jefferson wrote that news of the federal settlement reached him “like a fire bell in the night” and filled him with terror. The esteemed Virginian “considered it at once as the knell of the Union.” Likening the Missouri outcome to a pattern of bell-ringing used to signify a funeral procession, Jefferson viewed the general government’s ultimatum toward Missouri as a radical diversion from the Constitution. A strict adherent to what became known as the “equal footing doctrine,” Jefferson rejected any impulse that would diminish the sovereignty of new states by dictating positions on issues that were independently determined by each prior state.

Bolstering this perspective, Congress had inserted an explicit clause that reiterated this principle into each state’s enabling acts, from the 1791 admission of Vermont onward. The clause asserted that the state entered the union “on an equal footing with the original States, in all respects whatever.” Since new states would likely be carved out of the territory south of the line established by the Missouri Compromise, Jefferson feared this would create a new class of states that would be utterly subordinate to the existing states. The Missouri settlement, he thought, created a permanent schism would undermine the ratified conception of the federal union.