What Does the Militia Act of 1792 Tell Us About the Second Amendment?

By: Mike Maharrey

Whenever a debate comes up relating to the Second Amendment, somebody inevitably asserts that the right to keep and bear arms only applies to members of the National Guard.

They come to this conclusion based on the first clause of the Second Amendment – “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State…” But even if that clause limited the right to keep and bear arms to militia members – and it doesn’t – those who make the “National Guard only” argument don’t understand what the militia actually was at the time.

As I pointed out in an article taking on financial writer Brett Arends when he tried to play constitutional expert, the militia was made up the population at large – not a select group of professional soldiers. As George Mason said during the Virginia ratifying convention:

Mr. Chairman, a worthy member has asked who are the militia, if they be not the people of this country, and if we are not to be protected from the fate of the Germans, Prussians, &c., by our representation? I ask, Who are the militia? They consist now of the whole people, except a few public officers. But I cannot say who will be the militia of the future day. If that paper on the table gets no alteration, the militia of the future day may not consist of all classes, high and low, and rich and poor… [Emphasis added]

Practically speaking, “the whole people” generally meant all able-bodied white men. The point is the militia wasn’t a select military force. It was a defense force made up of the general population. In fact, part of the reason the Second Amendment was proposed was to ensure the people at large would not be disarmed and replaced by a “select militia.” I expand on this argument in my original takedown of Arends.

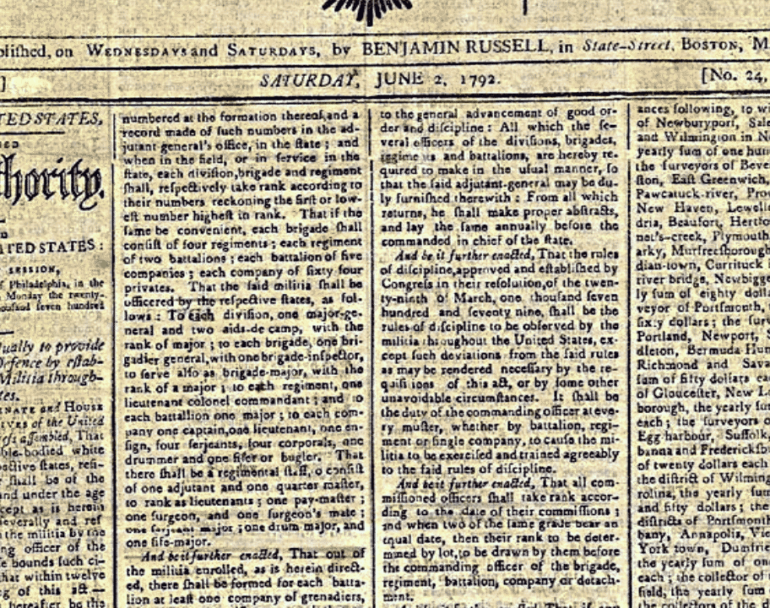

But I left out one bit of evidence that further undermines the “National Guard only” narrative. The Militia Acts of 1792 were some of the first bills passed by the First Congress. The Militia Act passed on May 8, 1792, defines the militia in a way that supports the broader understanding of the term used by Mason and others during the ratification debates.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress assembled, That each and every free able-bodied white male citizen of the respective States, resident therein, who is or shall be of age of eighteen years, and under the age of forty-five years (except as is herein after excepted) shall severally and respectively be enrolled in the militia, by the Captain or Commanding Officer of the company, within whose bounds such citizen shall reside, and that within twelve months after the passing of this Act. And it shall at all time hereafter be the duty of every such Captain or Commanding Officer of a company, to enroll every such citizen as aforesaid, and also those who shall, from time to time, arrive at the age of 18 years, or being at the age of 18 years, and under the age of 45 years (except as before excepted) shall come to reside within his bounds; and shall without delay notify such citizen of the said enrollment, by the proper non-commissioned Officer of the company, by whom such notice may be proved. That every citizen, so enrolled and notified, shall, within six months thereafter, provide himself with a good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch, with a box therein, to contain not less than twenty four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball; or with a good rifle, knapsack, shot-pouch, and powder-horn, twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound of powder; and shall appear so armed, accoutred and provided, when called out to exercise or into service, except, that when called out on company days to exercise only, he may appear without a knapsack. That the commissioned Officers shall severally be armed with a sword or hanger, and espontoon; and that from and after five years from the passing of this Act, all muskets from arming the militia as is herein required, shall be of bores sufficient for balls of the eighteenth part of a pound; and every citizen so enrolled, and providing himself with the arms, ammunition and accoutrements, required as aforesaid, shall hold the same exempted from all suits, distresses, executions or sales, for debt or for the payment of taxes. [Emphasis added]

So, pretty much every able-bodied free man was part of the militia.

You’ll also note that the act actually requires all men between the age of 18 and 45 to have military-grade weapons. This kind of undermines the whole, “the Second Amendment wasn’t so you could have an ‘assault rifles’” argument.

As I said in my original article, the debate over the militia is a bit overplayed. Preservation of state militias made up of the “whole body of people” was certainly part of the impetus that led to the ratification of the Second Amendment, but the right to keep and bear arms wasn’t exclusively attached to militia service. It was part of the broader natural right of self-defense. The text of the Second Amendment makes clear that the right to keep an bear arms applied to everybody. “The right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Not some of the people.

All of them.

And this was necessary because the militia included virtually all of the free men, as the Militia Act shows.

I don’t generally give a lot of weight to congressional acts, judicial opinions or presidential actions when it comes to determining the original meaning of the Constitution – even to those that occurred immediately after ratification. The federal government quickly went off the rails and began usurping power, and the fact that Congress, a president or a court did something doesn’t definitively prove it was constitutional. Nevertheless, the militia act reaffirms the definition of the militia expressed during the ratification debates by both opponents and supporters of the Constitution. It provides what I would call “supplemental evidence” that further strengthens the case.