The founder who told Americans we have a right to military weapons

By: Rob Natelson

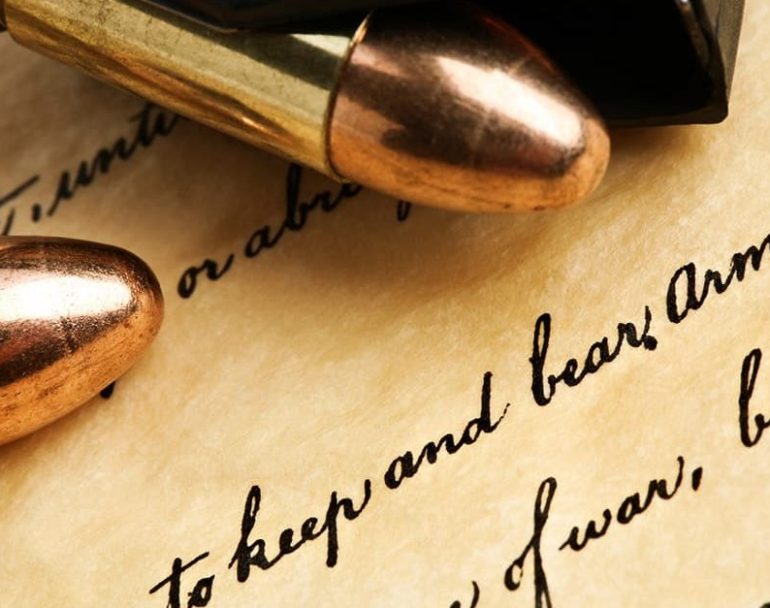

Does the Constitution’s right to keep and bear arms apply to everyone? Or only to law enforcement and the National Guard? Does the right include so-called “assault weapons?”

A newly published document from America’s founding offers a clue.

When interpreting the Constitution, judges and scholars consider what people said about the document around the time it was adopted. Writings by the Constitution’s advocates explaining its meaning to the general public are particularly helpful, because Americans relied on those explanations in deciding to ratify the document.

The most famous writings of this kind were penned by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay and collected as “The Federalist.” But there were many others. Among the most important were newspaper op-eds produced by Tench Coxe.

Few people know of Coxe today, but during the founding era he was famous. He served in the Confederation Congress. After the Constitution was ratified he became our first assistant secretary of the treasury, working directly under Alexander Hamilton.

Public release of the proposed Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787 ignited a massive public debate. Opponents argued that if the instrument were ratified it would create an all-powerful central government. Coxe supported the Constitution — and like Hamilton, Madison, and Jay, he was frustrated by opponents’ misrepresentations.

Coxe wrote a series of op-eds to accurately explain the Constitution’s legal effect. His informal style was much easier to understand than the scholarly tone of The Federalist, and his articles became extremely popular.

Many of Coxe’s op-eds were republished long ago, but new ones sometimes surface. The editors of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution recently issued new volumes that include four productions by Coxe previously known to only a few dedicated scholars.

In a Pennsylvania Gazette article published February 20, 1788, Coxe addressed the right to keep and bear arms: “The power of the sword, [opponents] say … is in the hands of Congress. My friends and countrymen, it is not so, for THE POWERS OF THE SWORD ARE IN THE HANDS OF THE YEOMANRY OF AMERICA FROM SIXTEEN TO SIXTY … Who are the militia? are they not ourselves[?].”

Coxe added, “The unlimited power of the sword is not in the hands of either the federal or state governments, but where I trust in God it will ever remain, in the hands of the people.”

In other words, all able-bodied adult men have the right to keep and bear arms — not just law enforcement and the military. (Since ratification of the 14th Amendment, women also possess the right.)

Coxe also addressed the kinds of arms included: “Their swords, and every other terrible implement of the soldier, are the birth-right of an American.” In other words, the right to keep and bear includes military arms, not just hunting pieces. Rifles such as the AR-15 (misleadingly branded “assault weapons”) are protected — not despite the fact that they are military weapons, but precisely because they are military weapons!

Coxe’s view is hardly surprising to those of us who study the founders: The Revolutionary War had ended only five years before. If American citizens had not possessed military-style weapons, we would have lost.

Coxe wrote further, “Congress have no power to disarm the militia. What clause in the state or federal constitution hath given away that important right[?]”

This passage was composed well before the Second Amendment was proposed. Even then, Congress had no power to disarm the people. This was part of Coxe’s wider argument that federal powers were strictly limited. In other op-eds, Coxe listed many other matters outside the federal sphere and reserved exclusively to the states: education, social services, agriculture, most business regulation, and others.

Despite the fact that Americans relied on such representations when ratifying the Constitution, the federal government now asserts almost unlimited authority. Since politicians always seek to expand their power, that is understandable. Unfortunately, writers on the Constitution often pervert history and constitutional meaning to provide “cover” to the politicians. An example is the ludicrous claim — promoted by some leading law professors — that the Constitution’s Commerce Clause granted Congress vast power over our national life.

Tench Coxe’s writings provide a useful corrective. They are valuable reading for anyone who wants to understand what the Constitution actually says.