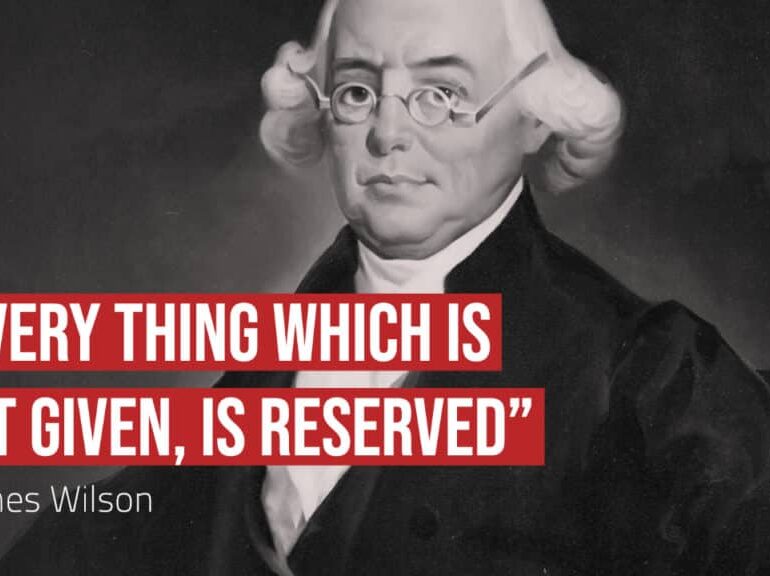

The First Salvo in the Ratification Debates: James Wilson’s State House Speech

By: Bob Fiedler

While most people today think of the Federalist Papers as the leading defense of the Constitution’s original meaning, it was actually a speech by James Wilson that had a far greater impact on ratification.

On September 17, 1787, the Philadelphia Convention, finished with drafting the instrument that would come to be the U.S. Constitution, sent it to the Confederation Congress to be presented to the states. The Anti-Federalists wasted no time in denouncing the document.

The first stand-alone counterattack against the Anti-Federalists took place in Philadelphia on October 6, 1787, when James Wilson, who had been a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention, addressed “a very large crowd of people” outside the State House where the Constitution had been signed three weeks earlier. In fact, he didn’t spend much time explaining or elucidating the proposed system of government created by the document but immediately moved on to strike back at the arguments made against the proposed Constitution.

Between the publications of the new Constitution on September 17 up to October 5, you can find six primary objections to the new Constitution that were commonly held and clearly identifiable.

- First, the Constitution did not create a reformed federal government to replace the Articles of Confederation, but a whole new monstrosity of a single, consolidated government.

- Second, the size of the United States would force this new consolidated government to rule with a heavy hand because its broad oversight responsibilities would require much more power.

- Third, the powers conferred on this new consolidated government were expressed in such vague terms – and here the trade clause and the necessary and appropriate clause were pointed out as the main villains – that no one could find a ground on which to stand against them.

- Fourth, the president and the Senate had too much power and were the seeds of a monarchy.

- Fifth, the new Congress would not have the power to maintain a professional national army.

- And sixth, there was no bill of rights.

The first great defense of the Constitution made by James Wilson quickly became one of the most well-known and most influential defenses of the Constitution during the whole of the ratification period between September 1787 and when the Constitution was ratified by nine of the 13 States, making it the Supreme Law of the Land in July 1788.

In that contemporaneous period, Wilson’s State House Speech was transcribed, published and disseminated in newspapers, leaflets and broadsides throughout all 13 States. Most people today view the Federalist Papers as the primary source explaining the Constitution, but Wilson’s speech was far more influential during the ratification period.

This speech led to some of the best anti-federalist responses at that time, written specifically to counter Wilson’s arguments set forth in his October 6 speech. Among the Anti-Federalist’s replies, several stand out – written in pseudo-anonymity by

- Centinel

- Cincinnatus

- A Democratic Federalist

- An Officer of the Late Continental Army

Wilson’s Speech — An Overview

Wilson went on the offensive, taking on a number of contentious issues.

Was there not a bill of rights in the Constitution?

“No” Wilson said, “and there shouldn’t be.”

When the people established the powers of legislation under their separate governments, they invested their representatives with every right and authority which they did not in explicit terms reserve. “If the frame of government is silent, the jurisdiction is efficient and complete. But in delegating federal powers the congressional power is to be collected, not from tacit implication, but from the positive grant expressed in the instrument of the union.” Wilson reiterated that in state constitutions, everything which is not reserved is given. “Whereas, in the instrument of federal power, everything which is not given is reserved.”

To Wilson, this distinction furnished an answer to those who viewed the omission of a bill of rights a defect in the proposed constitution; “for it would have been superfluous and absurd to have stipulated with a federal body of our own creation that we should enjoy those privileges of which we are not divested.”

Wilson focuses on claims the Federal government may shackle or destroy the liberty of the press. But where he asks is the federal government granted control over “that sacred palladium of national freedom? ”

If, indeed, a power similar to that which has been granted for the regulation of commerce had been granted to regulate literary publications, it would have been as necessary to stipulate that the liberty of the press should be preserved inviolate. There is no reason to suspect that so popular a privilege will in that case be neglected.”

Wilson brushes off concerns about standing armies in times of peace as disingenuous. He argues that every nation has found standing armies in peacetime necessary and useful, insinuating the appearance of military strength in peacetime is itself, the best assurance of long-term tranquility. He seemingly overlooks the fact that even the most militaristic of the Founders recognized, that in times of external peace, standing armies often become the instrument of internal oppression.

Considering Wilson’s extensive knowledge of the classical historians of the Roman Republic, he would have known that since the Marian Reforms of 107 BC, arguably creating the world’s first truly professional, standing army under Gaius Marius, it was well-known that peacetime armies needed to be kept busy with the make-work of civil engineering Rome’s famous road and aqueducts, as idle soldiers had a habit of becoming seditious soldiers.

Perhaps the least satisfying of his assurances was his rejection of the Senate as too aristocratic in its form and too powerful in its function, because, “it can accomplish nothing without the cooperation of the more democratic House of Representatives.” He overlooks the glaringly obvious concern that arises from the Senate’s sole power of affirming federal judges, ratifying treaties and trying articles of impeachment.

The inconsistencies of this defense are compounded by the fact James Wilson was arguably the most ardent supporter of the Virginia Plan’s nationalist proposal that the Senate, like the House, be subject to direct election, in proportion to population. Wilson continued to hold out, even after the notoriously stubborn nationalists like Madison and Hamilton both assented to Roger Sherman’s Great Compromise., making Wilson the Convention’s last “no compromise” delegate on popular representation in the Senate.

His final remarks express an absolute faith in the Convention’s wisdom in choosing to create a new consolidated government, rather than the expected reform of the purely federal system that had existed under the Articles of Confederation:

I am satisfied that anything nearer to perfection could not have been accomplished. If there are errors, it should be remembered that the seeds of reformation are sown in the work itself. I am bold to assert that it is the best form of government which has ever been offered to the world.

You can read the full text of the State House Speech HERE.

In following articles, I will outline some of the anti-federalist responses to Wilson’s speech.