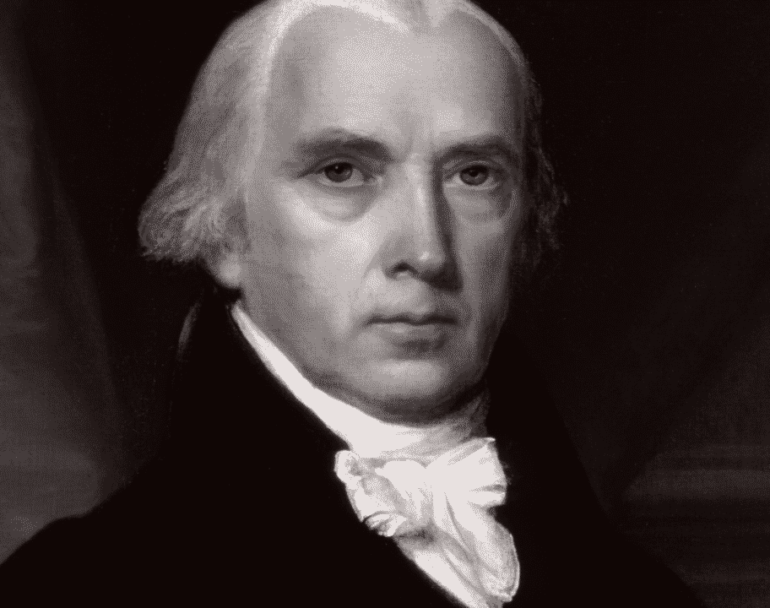

James Madison on War as a Great Threat to Liberty

By: Tenth Amendment

Excerpted from Political Observations, 20 April 1795

Of all the enemies to public liberty war is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it comprises and develops the germ of every other. War is the parent of armies; from these proceed debts and taxes; and armies, and debts, and taxes are the known instruments for bringing the many under the domination of the few. In war, too, the discretionary power of the Executive is extended; its influence in dealing out offices, honors, and emoluments is multiplied; and all the means of seducing the minds, are added to those of subduing the force, of the people. The same malignant aspect in republicanism may be traced in the inequality of fortunes, and the opportunities of fraud, growing out of a state of war, and in the degeneracy of manners and of morals, engendered by both. No nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare.

Those truths are well established. They are read in every page which records the progression from a less arbitrary to a more arbitrary government, or the transition from a popular government to an aristocracy or a monarchy.

It must be evident, then, that in the same degree as the friends of the propositions were jealous of armies, and debts, and prerogative, as dangerous to a republican Constitution, they must have been averse to war, as favourable to armies and debts, and prerogative.

The fact accordingly appears to be, that they were particularly averse to war. They not only considered the propositions as having no tendency to war, but preferred them, as the most likely means of obtaining our objects without war. They thought, and thought truly, that Great Britain was more vulnerable in her commerce than in her fleets and armies; that she valued our necessaries for her markets, and our markets for her superfluities, more than she feared our frigates or our militia; and that she would, consequently, be more ready to make proper concessions under the influence of the former, than of the latter motive.

Great Britain is a commercial nation. Her power, as well as her wealth, is derived from commerce. The American commerce is the most valuable branch she enjoys. It is the more valuable, not only as being of vital importance to her in some respects, but of growing importance beyond estimate in its general character. She will not easily part with such a resource. She will not rashly hazard it. She would be particularly aware of forcing a perpetuity of regulations, which not merely diminish her share; but may favour the rivalship of other nations. If anything, therefore, in the power of the United States could overcome her pride, her avidity, and her repugnancy to this country, it was justly concluded to be, not the fear of our arms, which, though invincible in defence, are little formidable in a war of offence, but the fear of suffering in the most fruitful branch of her trade, and of seeing it distributed among her rivals.

If any doubt on this subject could exist, it would vanish on a recollection of the conduct of the British ministry at the close of the war in 1783. It is a fact which has been already touched, and it is as notorious as it is instructive, that during the apprehension of finding her commerce with the United States abridged or endangered by the consequences of the revolution, Great-Britain was ready to purchase it, even at the expence of her West-Indies monopoly. It was not until after she began to perceive the weakness of the federal government, the discord in the counteracting plans of the state governments, and the interest she would be able to establish here, that she ventured on that system to which she has since inflexibly adhered. Had the present federal government, on its first establishment, done what it ought to have done, what it was instituted and expected to do, and what was actually proposed and intended it should do; had it revived and confirmed the belief in Great-Britain, that our trade and navigation would not be free to her, without an equal and reciprocal freedom to us, in her trade and navigation, we have her own authority for saying, that she would long since have met us on proper ground; because the same motives which produced the bill brought into the British parliament by Mr. Pitt, in order to prevent the evil apprehended, would have produced the same concession at least, in order to obtain a recall of the evil, after it had taken place.

The aversion to war in the friends of the propositions, may be traced through the whole proceedings and debates of the session. After the depredations in the West-Indies, which seemed to fill up the measure of British aggressions, they adhered to their original policy of pursuing redress, rather by commercial, than by hostile operations; and with this view unanimously concurred in the bill for suspending importations from British ports; a bill that was carried through the house by a vote of fifty-eight against thirty-four. The friends of the propositions appeared, indeed, never to have admitted, that Great-Britain could seriously mean to force a war with the United States, unless in the event of prostrating the French Republic; and they did not believe that such an event was to be apprehended.

Confiding in this opinion, to which Time has given its full sanction, they could not accede to those extraordinary measures, which nothing short of the most obvious and imperious necessity could plead for. They were as ready as any, to fortify our harbours, and fill our magazines and arsenals; these were safe and requisite provisions for our permanent defence. They were ready and anxious for arming and preparing our militia; that was the true republican bulwark of our security. They joined also in the addition of a regiment of artillery to the military establishment, in order to complete the defensive arrangement on our eastern frontier. These facts are on record, and are the proper answer to those shameless calumnies which have asserted, that the friends of the commercial propositions were enemies to every proposition for the national security.

But it was their opponents, not they, who continually maintained, that on a failure of negotiation, it would be more eligible to seek redress by war, than by commercial regulations; who talked of raising armies, that might threaten the neighbouring possessions of foreign powers; who contended for delegating to the executive the prerogatives of deciding whether the country was at war or not, and of levying, organizing, and calling into the field, a regular army of ten, fifteen, nay, of twenty-five thousand men.15

It is of some importance that this part of the history of the session, which has found no place in the late reviews of it, should be well understood. They who are curious to learn the particulars, must examine the debates and the votes. A full narrative would exceed the limits which are here prescribed. It must suffice to remark, that the efforts were varied and repeated until the last moment of the session, even after the departure of a number of members; forbade new propositions, much more a renewal of rejected ones; and that the powers proposed to be surrendered to the executive, were those which the constitution has most jealously appropriated to the legislature.

The reader shall judge on this subject for himself.

The constitution expressly and exclusively vests in the legislature the power of declaring a state of war: it was proposed, that the executive might, in the recess of the legislature, declare the United States to be in a state of war.

The constitution expressly and exclusively vests in the legislature the power of raising armies: it was proposed, that in the recess of the legislature, the executive might, at its pleasure, raise or not raise an army of ten, fifteen, or twenty-five thousand men.

The constitution expressly and exclusively vests in the legislature the power of creating offices: it was proposed, that the executive, in the recess of the legislature, might create offices, as well as appoint officers for an army of ten, fifteen, or twenty-five thousand men.

A delegation of such powers would have struck, not only at the fabric of our constitution, but at the foundation of all well organized and well checked governments.

The separation of the power of declaring war, from that of conducting it, is wisely contrived, to exclude the danger of its being declared for the sake of its being conducted.

The separation of the power of raising armies, from the power of commanding them, is intended to prevent the raising of armies for the sake of commanding them.