Why the Founders Wanted You to Own Military-Style Weapons

By: TJ Martinell

Two hundred and twenty-seven years ago this month, the U.S. Congress passed the Militia Acts of 1792. This pair of bills authorized the president to lead the state militias in war and to conscript all able-bodied free men to fight with self-provided arms and munitions.

To a modern American living in the midst of an empire with a permanent military presence both here and abroad, there might be little reason to acknowledge this anniversary. However, it offers an example of how the founders believed military defense and war should be handled, and why so many modern arguments against civilian gun ownership don’t match the history.

The first Militia Act was passed on May 2, followed shortly thereafter by the second Act on May 8. The first act gave the president the power to call up the militia “whenever the United States shall be invaded, or be in imminent danger of invasion from any foreign nation or Indian tribe.” The second Act called on every “free able-bodied white male citizen” between the ages of 18-45 to join a militia.

Why are these laws relevant today?

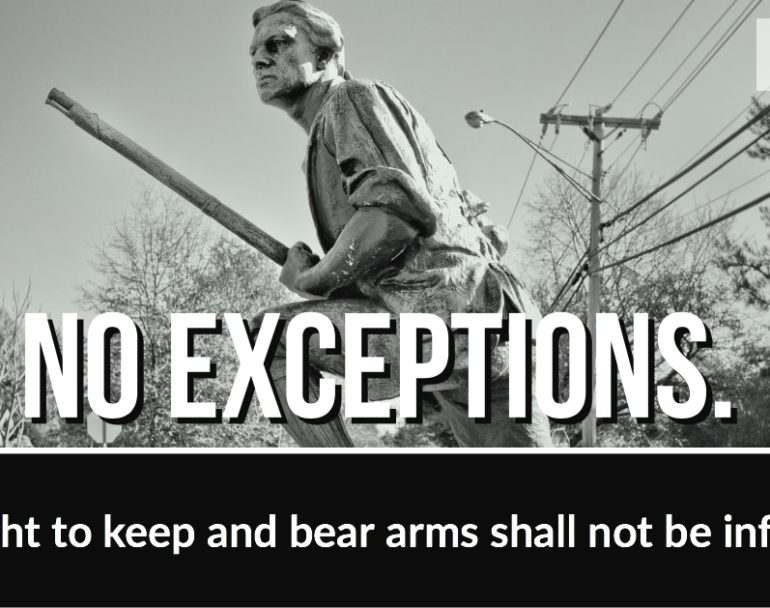

We live in a time when Americans are told by self-appointed “wise overlords” that the founders never intended for private citizens to have military weapons. Incidentally, they never cite anyplace that the founders made this assertion, nor where they declared their love for intervening in other countries’ domestic affairs, endless unconstitutional wars, and a permanent military with bases in foreign nations for that matter. This argument is used to justify gun control policies that restrict our right to keep and bear arms as described in the Second Amendment.

The reality is that many in the founding generation were terrified of a permanent, standing army that could crush liberties at home. This fear was a major theme during the Virginia Ratifying Convention in 1788. In fact, the convention’s proposed Second Amendment text makes it clear why it was so important that the proposed central government had no say in the possession of firearms by Americans (bold emphasis added):

That the people have a right to keep and bear arms; that a well-regulated militia, composed of the body of the people trained to arms, is the proper, natural, and safe defence of a free state; that standing armies, in time of peace, are dangerous to liberty, and therefore ought to be avoided, as far as the circumstances and protection of the community will admit; and that, in all cases, the military should be under strict subordination to, and governed by, the civil power.

The convention’s “Second Amendment” draft also provides another glimpse into their worldview. The country’s defense was to come from the people, not an army held to a different legal standard. There was no separation between soldier and civilian. At the convention, George Mason referred to the militia as “the whole of the people.” In every colony besides Pennsylvania, able-bodied men not only had to join a militia and show up to musters, but they had to furnish their own functioning arms.

The Militia Acts show that this tradition carried on through Colonial America into its history as an independent country apart from Great Britain and under the newly-approved U.S. Constitution.

Under the Militia Acts, the militia members had to bring the following:

A good musket or firelock, a sufficient bayonet and belt, two spare flints, and a knapsack, a pouch, with a box therein, to contain not less than twenty four cartridges, suited to the bore of his musket or firelock, each cartridge to contain a proper quantity of powder and ball; or with a good rifle, knapsack, shot-pouch, and powder-horn, twenty balls suited to the bore of his rifle, and a quarter of a pound of powder; and shall appear so armed, accoutered and provided.

The militiamen were to be armed with their own weapons, not ones provided and owned by the federal government.

Now some might argue the U.S. government lacked the financial resources it does today, but that’s why it’s important to look at the broader context of the law. The founders did not want a standing army, and there were no calls for these men to surrender their personal firearms once a military crisis had been addressed.

Ultimately, free men must be the ones responsible for defending their liberties and their country if that freedom is to last. The founders believed that, and it’s why they favored a militia-style military composed self-equipped men, which would reduce the risk of a standing army that would take that responsibility away. If free men are not responsible, then they are not really in charge – and thus they are not truly free.

A constitutionalist or someone sympathetic to anti-federalist concerns might take issue with the law and how it was used to call up the militia during the Whiskey Rebellion. However, the Militia Acts offer reveal the blueprint for how the founders believed wars should be fought, and why they made it clear the central government should have no right to infringe on the people’s right to keep and bear arms.