Totally Dissolved: The Lee Resolution and the Declaration of Independence

By: Dave Benner

Today in history, on July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress passed the Richard Henry Lee resolution, which called for ties between Great Britain and the American states to be “totally dissolved.”

The monumental vote was unanimous among the colonies, with New York abstaining. Each state had one vote, regardless of size.

Initially reluctant to support this measure, South Carolina pledged to join with the majority provided that there would be no dissent from a vote of independence. New York had not yet received instructions from its legislature to vote in favor, and British Admiral Richard Howe amassed a huge fleet of ships around Long Island. Still, New York’s state government gave its delegates permission to support this cause a week later. However, several states had already declared independence prior to this point.

By July 2, some still clung to hope for a peaceful reconciliation with Great Britain, and delegates such as John Dickinson, one of the most famous Americans of the era, refused to sign the document. Others felt that if they authorized a vote of independence, their state would be treated as Massachusetts had.

Following the agitation in Boston, Britain dissolved the autonomy of the Massachusetts government, closed Boston’s port, imposed a quartering law, and besieged the colony.

Upon the decision to secede from the British crown, a somber mood swept through Independence Hall as the delegates realized their actions would be considered treasonous. Despite the prospect of death by hanging, the decision had been made. Historian Mercy Otis Warren wrote this account of the event:

“Their transactions might have been legally styled treasonable, but loyalty had lost its influence, and power its terrors. Firm and disinterested, intrepid and united, they stood ready to submit to the chances of war, and to sacrifice their devoted lives to preserve inviolate, and to transmit to posterity, the inherent rights of men, conferred on all by the God of nature, and the privileges of Englishmen, claimed by Americans from the sacred sanctions of compact.”

In response to the resolution, John Adams believed that July 2nd would be celebrated as the most extraordinary holiday in America, and wrote to his wife Abigail:

“The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

While Adams did not realize the date of the Declaration of Independence’s acceptance two days later would be the more recognizable and celebrated occasion, he fully grasped the significance of the day and its eternal importance.

Ironically, Adams would later attempt to diminish the significance of the moment, while Jefferson received much adulation for its philosophical influence as he became the lead opponent of the Adams administration.

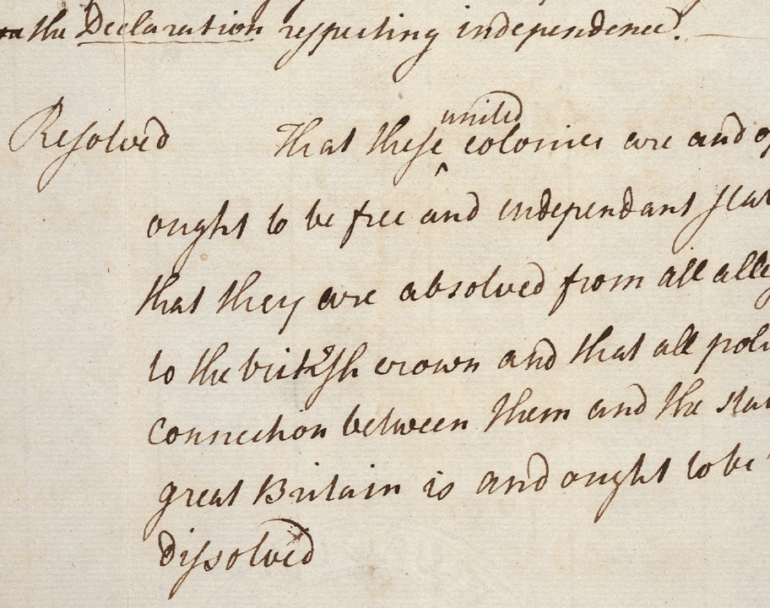

TEXT OF LEE’S RESOLUTION

“Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

“That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign Alliances.”

“That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.”