The Anti-Commandeering Doctrine Isn’t About Constitutionality

State and local governments can legally refuse to cooperate with the enforcement of federal laws and the implementation of federal programs. And this is key – whether those laws or programs are constitutional or not.

Refusal to cooperate with federal enforcement rests on a well-established legal principle known as the anti-commandeering doctrine based primarily on five Supreme Court cases dating back to 1842. Under this legal doctrine, the federal government cannot require states to expend resources or provide personnel to help it carry out its acts or programs.

The Court first established the doctrine in the 1842 fugitive slave case Prigg v. Pennsylvania. Justice Joseph Story held that the federal government could not force states to implement or carry out the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. He said that it was a federal law, and the federal government ultimately had to enforce it. Over the years, the Court built on this decision in four more landmark cases. Printz v. U.S. serves as the cornerstone.

“We held in New York that Congress cannot compel the States to enact or enforce a federal regulatory program. Today we hold that Congress cannot circumvent that prohibition by conscripting the States’ officers directly. The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems, nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program. It matters not whether policy making is involved, and no case by case weighing of the burdens or benefits is necessary; such commands are fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system of dual sovereignty”

Again — this is key — no determination of constitutionality is necessary to invoke the anti-commandeering doctrine.

State and local governments can refuse to enforce federal laws or implement federal programs for any reason they choose. They can prohibit or limit cooperation with the feds because they think the feds are acting outside of their constitutional limits, or simply because it’s Tuesday and there is snow on the ground.

Some states and localities have used the anti-commandeering doctrine to create “immigration sanctuaries” by refusing to participate in the enforcement of some federal immigration laws. Gun rights activists in some states and cities have copied the model to create Second Amendment sanctuaries that prohibit or limit participation in the enforcement of federal gun control. Both are viable, legal, and constitutional applications of the anti-commandeering doctrine in practice.

But some conservatives don’t get it. They seem to think Second Amendment sanctuaries are OK but immigration sanctuaries are not because the Constitution protects the right to keep and bear arms but it does not protect undocumented immigrants. As one commenter on Twitter put it, “Well at least the right to bear arms is literally in the constitution. Not so much for immigration sanctuaries.”

Some liberals don’t get it either. They seem to think immigration sanctuaries are OK but Second Amendment sanctuaries are not for equally unfounded claims, such as, “immigration isn’t listed in the constitution and arms are, so we have to follow the restrictions that the Supreme Court has said are constitutional.”

But again, and I can’t emphasize this enough, whether or not something is or isn’t “in the constitution” isn’t the point.

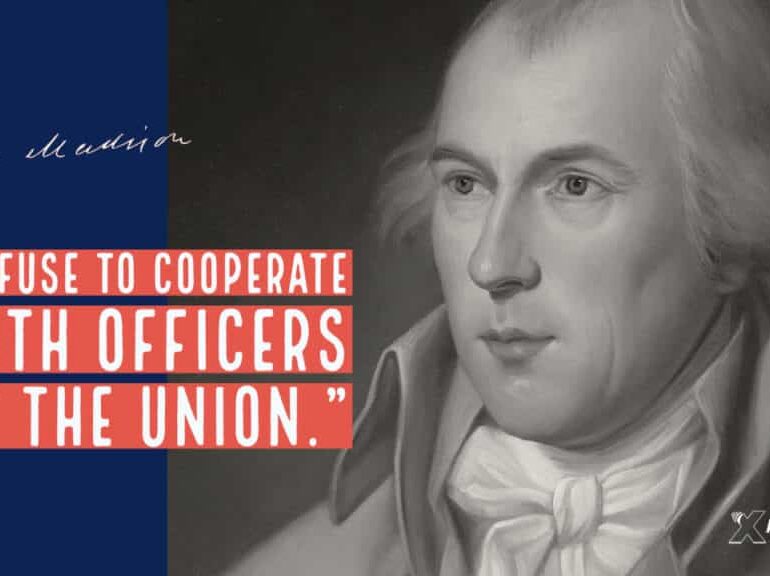

As a strategy to limit federal power, the roots of the anti-commandeering doctrine predate the ratification of the Constitution. In Federalist #46, James Madison gave us a blueprint, writing that when confronted with an “unwarrantable” federal act (meaning unconstitutional) states could “create obstructions” through “a refusal to cooperate with officers of the union.” Significantly, Madison said the same strategy should be applied to a “warrantable” (constitutional) act that happened to be unpopular.

As Tenth Amendment Center executive director Michael Boldin noted, “States and localities are banning state and local resources from helping implement a federal program whether it be the enforcement of gun control or immigration enforcement. This strategy is being used exactly the same way on both issues.”

The crux of the anti-commandeering doctrine is that a state has the right to direct its personnel and resources as it sees fit. It can prohibit the enforcement of federal laws or the implementation of federal programs for any reason at all. That’s exactly what these sanctuary jurisdictions are doing.”

But these conservatives and liberals want to condone one action, while condemning the other, based on constitutionality. As Boldin points out, these hypocrites are literally saying, “It’s OK under the Constitution to stop helping the feds…unless I oppose the issue politically.”

“They’re conflating the words ‘constitutional’ and ‘unconstitutional’ with ‘things I support’ and ‘things I oppose.’”

Because – again – constitutionality has no bearing on the legitimacy of anti-commandeering.

The anti-commandeering doctrine doesn’t care about the constitutionality of the issue it’s being applied to. And it doesn’t care about your policy preferences. It is based solely on the fact that states and localities have the right to control their own personnel and resources and deploy them (or not deploy them) as they see fit.