Restoring the Fourth Amendment’s Oath or Affirmation Clause

The Fourth Amendment’s requirements for obtaining a warrant have been subverted in practice and in legal theory.

That’s the argument made in “The Broken Fourth Amendment’s Oath” paper written by Law Professor Laurent Sacharoff. The paper focuses on the need for credible evidence before the government can obtain search warrants.

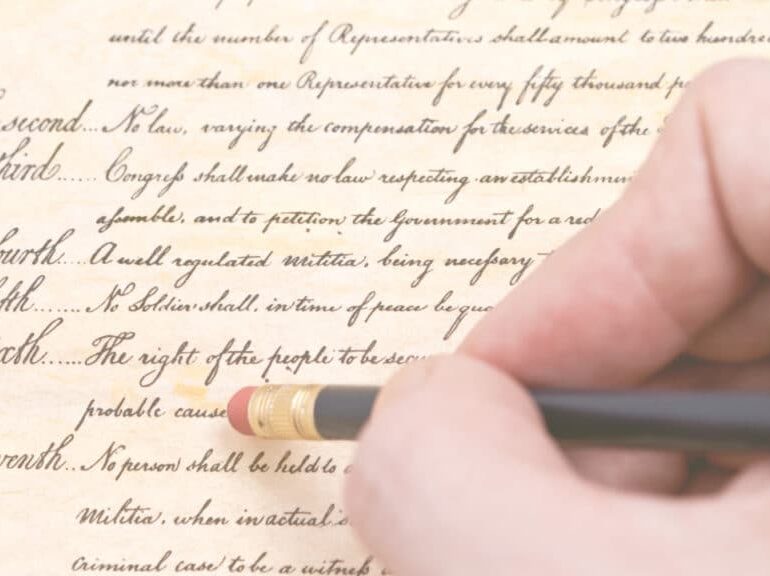

The Fourth Amendment states the following (bold emphasis added):

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

“The Fourth Amendment’s ‘oath’ is a topic strangely ignored—even simply to address the strange idea that officers can swear the ‘oath’ simply repeating another’s account,” Sacharoff writes. “We should restore the Fourth Amendment oath requirement that the real accuser swears the oath based upon personal knowledge.”

The intent of the oath requirement was to ensure that government agents would offer more than just rumors, hearsay, or their own personal prejudices to justify entering private property without the consent of the owner. It was meant to provide accountability and guardrails against misuse of warrants Yet, Sacharoff notes that judges today spend little time reviewing warrant requests, citing a study that concluded they spend an average of two minutes looking at each warrant application.

Sacharoff documents the long tradition within the Anglo legal system of requiring oaths to affirm testimony that would be used for an arrest, warrant, or for conviction.

“This goal, to protect the liberty of the individual against unfounded searches or arrests, works best if it is the real accuser with personal knowledge who swears the oath and subjects himself to examination by the magistrate. To examine an officer merely repeating another’s account does little to assure the allegations themselves are true, when the person who originally made it. Perjury and trespass are thus a foundational part of the Fourth Amendment, and their details support a real accuser requirement. Perjury required not only an oath, but one in which the person makes a ‘positive,’ ‘direct” or ‘absolute’ assertion of truth, and not mere belief.”

Prior to the War of Independence, the British government set up a new legal process to obtain search and warrants for seditious activities in England, as well as revenue searches in colonial America.

“Both efforts led to legal battles that became the foundation for the Fourth Amendment,” Sacharoff wrote. “These writs did not require an oath at all. Courts in Massachusetts, for example, simply granted the writ to a customs officer as standing authority, like a commission, to use for any case he should decide, in his discretion, to use. From the 1760s until the revolution, the courts in many colonies rejected the writs because they were general and without oath, though sometimes they would grant special writs based on oath. In Massachusetts and the few other states where the writs remained lawful, officers almost never sought or executed such writs because the people would interfere and prevent any seizure or, after a seizure, rescue the ship or other property seized.”

Much has changed since the Bill of Rights was ratified. Thanks to cases like Brinegar v. United States and Draper v. United States, the modern practice of obtaining warrants allows the use of unnamed or confidential informants. Not only does it violate the spirit of the amendment itself, but practically speaking, it opens the risk of warrants beaded on noncredible information.

Describing the deadly raid on Breonna Taylor’s home in 2019, Sacharoff writes:

“Officers were investigating drug dealing by Jamarcus Glover out of his home miles away from where Breonna Taylor lived. But officers suspected that they would find drugs, proceeds, or records in Taylor’s home as well. The investigating police detective suspected this in part because Taylor was supposedly ‘receiving packages’ for Glover at her home. How did the detective know this?—third hand, from an unnamed source In his affidavit to obtain the warrant, the detective swore that an unnamed postal inspector had told him Taylor was receiving Glover’s packages. Note the supposed postal inspector did not come into court to tell the judge directly. The judge relied upon this third-hand account, found probable cause, and issued the warrant to search Taylor’s home. Based upon this warrant, the police raided Breonna Taylor’s home, near midnight, battering in. Taylor’s boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, terrified, gave one warning shot against the unknown and, to him, unannounced intruders. They respond with overwhelming gunfire, killing Taylor. I argue that the Fourth Amendment as originally understood would likely have prevented this raid.”

Sacharoff also notes that the use of unnamed informants to get search warrants is exercised routinely in cities like Chicago and, like with Breonna Taylor, to disastrous results. One such case involved a SWAT team conducting a no-knock raid on the wrong home due to a “bad tip” by an informant.

“If the informer had been required to testify, under oath, before a judge, that informant either would not have testified at all, or have made sure to be accurate before knowingly sending a SWAT team into someone’s home,” Sacharoff writes.

He concludes:

“Under current Supreme Court doctrine, the ‘oath or affirmation’ requirement in the Fourth Amendment allows officers to swear the oath merely to repeat, third-hand, the allegations of the real accuser. This hyper-literal expedient contradicts the original understanding of the oath requirement. We should therefore return to the original requirement that the real accuser, with personal knowledge, swear the oath before a judge issues a warrant. This requirement will help reduce the widespread abuse of search warrants to authorize violent, night-time home intrusions based on faulty confidential informants. the same reasons that drove the founding era to insist that the real accuser swear the oath remain as strong today: the need for truth and accountability to justify such drastic intrusions into liberty and the security of the home in particular.”