Resistance is Crucial to the Advancement of Liberty

By: Mike Maharrey

Patrick Henry told us that “government is no more than a choice among evils.”

Thomas Paine held the same view. In Common Sense, he wrote, “Society in every state is a blessing, but Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one.”

What makes government become intolerable?

Consolidation.

That was the term the founding generation used to describe a centralized government with vast power and control – the kind of government we have today.

During the Virginia Ratifying Convention, Patrick Henry warned against consolidation.

“Dangers are to be apprehended in whatever manner we proceed; but those of a consolidation are the most destructive.” [Emphasis added]

He went on to predict that consolidation would, “end in the destruction of our liberties.”

History proved Henry correct.

If consolidation ends in the destruction of our liberties, the key to regaining liberty is “un-consolidation,” or to use an actual word — decentralization.

Political decentralization devolves and distributes political power. This promotes competition in the political marketplace, with various jurisdictions opposing and checking growing power in others.

Most people intuitively understand the problems inherent in economic monopolies. With no competition, a monopolist can easily abuse its customers. It can limit selection. It can raise prices. It can get away with crappy customer service.

Now, think of the federal government as a monopoly. Because that’s exactly what it is.

We need to break the monopoly if we want to regain liberty. We need to decentralize, disperse and minimize political power in order to shrink government to, as Paine put it, “its best state … a necessary evil.”

This strategy requires letting go of centralized political power. That includes resisting the temptation to try to wrest control of the overreaching consolidated government and impose liberty from on high.

This is a difficult concept to grasp in an American political culture that operates almost exclusively through the consolidated government in Washington D.C. People always tend to think in terms of grabbing and wielding political power. This will always fail because political power is the problem.

But a lot of people argue that you need political power to force decentralization. As one person put it, “The great paradox is that in order to diffuse power, you must first acquire it.”

This is wrong.

The paradox is that forcing a diffusion of power is actually a centralization of power. In order to diffuse power, you must first resist it.

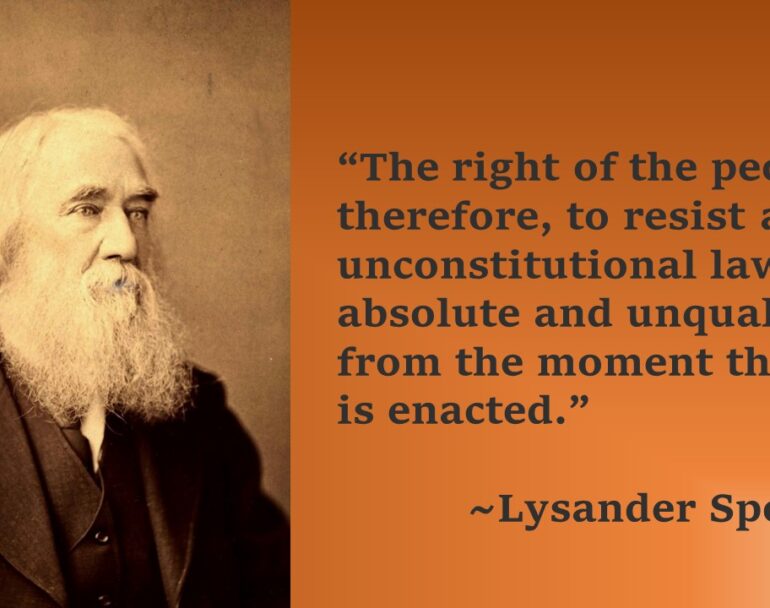

Lysander Spooner nailed it on resistance.

“The right of the people, therefore, to resist an unconstitutional law, is absolute and unqualified, from the moment the law is enacted.”

He called resistance “a constitutional right.”

“And the exercise of the right is neither rebellion against the constitution, nor revolution—it is a maintenance of the constitution itself, by keeping the government within the constitution.”

At the Tenth Amendment Center, we talk a lot about resisting overreaching federal power through state and local action. This leads people to believe they have to consolidate power at the state or local level. Having political allies in state and local government certainly helps, but it’s not necessary. And it’s certainly not the first step.

It starts with people resisting.

Think about the nullification of federal marijuana prohibition. Before California legalized medical marijuana in 1996, there were a lot of people who were willing to violate the “law” and use cannabis anyway. It was that groundswell of resistance that led to political changes at the state level. Rosa Parks offers another example. Her willingness to say, “No!” to an unjust law sparked more widespread resistance that eventually led to political change.

Necessity forced the American colonists to adopt a strategy of resistance. They had no political power – and there was no way they were ever going to gain any in faraway London. They had two choices – resist or submit.

They chose to resist.

The Sugar Act in 1764 sparked resistance and it ramped up significantly with the passage of the Stamp Act in March 1765.

The Stamp Act required all official documents in the colonies to be printed on special stamped paper. This included all commercial and legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards. As historian Dave Benner explained in his article on the Stamp Act, the standard American position held that the act violated the bounds of the British constitutional system. Objecting to the notion that Parliament was supreme, and could impose whatever binding legislation it wished upon the colonies, the colonies instead adopted the rigid stance that colonists could only be taxed by their local assemblies. They claimed this principle stretched all the way back to 1215 and the Magna Carta.

Resistance started with protests. Patrick Henry drafted a series of resolutions. In the seventh, He asserted, “the Inhabitants of this Colony, are not bound to yield Obedience to any Law or Ordinance whatever,” outside of those passed by the colonial assemblies.

John Dickinson wrote, “IF you comply with the Act by using Stamped Papers, you fix, you rivet perpetual Chains upon your unhappy Country. You unnecessarily, voluntarily establish the detestable Precedent, which those who have forged your Fetters ardently wish for, to varnish the future Exercise of this new claimed Authority.”

John Hancock was perhaps most emphatic, declaring, “The people of this country will never be made slaves of by a submission to the damned act.”

They didn’t.

Patriots throughout the 13 colonists blocked the distribution of stamped paper, forced stamp agents to resign, and effectively made that act impossible to enforce. Ultimately, mass resistance and noncompliance forced Parliament to repeal the hated law.

Historian Dave Benner summed up colonial resistance this way.

“Rather than hoping the next election will produce preferable results or waiting for the courts to weigh in on controversial law, the patriots took a fierce stand against an odious law. In doing so, they inspired tireless masses to their cause, brought about a reversal of policy without representation in Parliament, and changed the world as we know it.”

The problem is this strategy is scary, hard, and often requires sacrifice. Many people felt the heavy hand of the law in the early days of the movement to nullify marijuana prohibition. Rosa Parks went to jail. And the British ultimately drug American colonists into a war.

On the other hand, politics is relatively easy. You just gain power and then impose your will. But this is the antithesis of liberty. And at some point, the political pendulum will swing away from you as it always does and people you hate will control that power.

There is no easy path to liberty. As Thomas Paine wrote, “Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom, must, like men, undergo the fatigues of supporting it.”