Patrick Henry’s Virginia Resolves of 1765: Spark of the Revolution

By: Michael Boldin

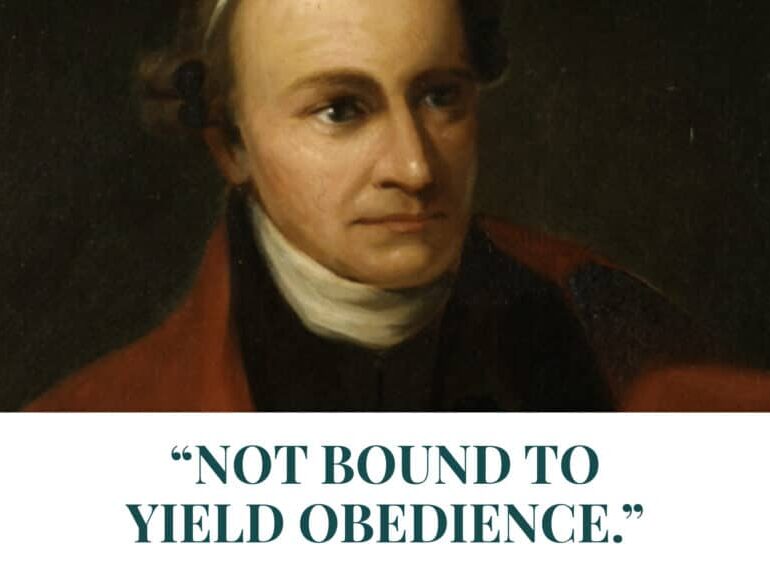

“Not bound to yield obedience.”

That was no mere slogan. It was a warning – and a call to action printed across the colonies in 1765.

The British had just passed the hated Stamp Act. But in Virginia, a 29-year-old freshman legislator named Patrick Henry pushed back – hard. His Virginia Resolves didn’t just protest a tax, they rejected Parliament’s power outright. And when government tried to silence him, Henry stood firm, and the other colonies joined in – publishing every single word.

The fuse was lit.

THE FRESHMAN TAKES HIS STAND

The story starts in March 1765 when Parliament passed the Stamp Act – a raw assertion of power over the colonies.

As historian Joe Wolverton writes, “News of the Act’s passage reached Virginia in April 1765, but the sparks really didn’t begin flying until May, when a young, newly elected member from the county of Louisa took the ancient oath of office and set out to use all his talents to fight this latest example of British tyranny. That brash young firebrand was, of course, Patrick Henry.”

Henry took his seat in the House for the first time on May 20th. He was just 28 years old. Nine days later, on May 29, 1765, the day of his 29th birthday, he presented a series of resolutions against the Stamp Act for consideration by the House of Burgesses.

He had some allies too. Shortly before offering his resolutions to the House, he shared them with George Johnston and John Fleming – both of whom pledged their support for passage.

RIGHTS BY INHERITANCE, NOT GRANT

Henry’s first resolution cut straight to the heart: Virginians held their rights by inheritance, not permission.

“The first adventurers and settlers of this his majesty’s colony brought with them, and transmitted to their posterity, and all other his majesty’s subjects since inhabiting in this his majesty’s said colony, all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities that have at any time been held, enjoyed, and possessed by the people of Great Britain.”

Next, Henry pointed out that this was confirmed by their charter.

“by two royal Charters, granted by King James the First, the Colonists aforesaid are declared entitled to all the Liberties, Priviledges, and Immunities of Denizens and natural Subjects, as if they had been abiding and born within the Realm of England.”

Not radical claims. Established law. Virginians had the same rights as Englishmen – period.

PRINCIPLE AND TRADITION

Henry’s third resolution first affirmed the principle of no taxation without representation.

“The Taxation of the People by themselves, or by Persons chosen by themselves to represent them”

He then explained the practical logic behind this. Distant lawmakers who don’t feel the pinch will keep squeezing until the people break.

Only representatives “who can only know what Taxes the People are able to bear, or the easiest Mode of raising them, and must themselves be affected by every Tax laid on the People, is the only Security against a burdensome Taxation, and the distinguishing Characteristick of British Freedom, without which the ancient Constitution cannot exist.”

That’s how tyranny always works – it’s easy to rob people when the robbers don’t pay the cost.

The fourth resolution asserted principles later enshrined in the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution – Henry’s distinction between matters of general concern versus “internal policy and taxation” that could only come from the people’s local representatives.

The people, Henry noted, “have without Interruption enjoyed the inestimable Right of being governed by such Laws, respecting their internal Policy and Taxation, as are derived from their own Consent.”

Henry then pointed to history and tradition. Because Virginians had never surrendered this right, Parliament was grabbing power it never possessed.

“Having never ceded to any other Power whatever a Right to lay Taxes and Impositions upon them, they have ever since enjoyed the Right of being exempt from any Taxation other than by the Virginia General Assembly.”

UNCONSTITUTIONAL, ILLEGAL

Henry’s fifth resolution brought his constitutional argument to its logical conclusion. Having established that Virginians possessed inherent English rights, that these rights were confirmed by royal charter, and that self-taxation through consent was both principle and tradition, Henry now declared that Virginia alone held legitimate taxing authority.

“The General Assembly of this Colony, together with his Majesty or his Substitutes, have, in their Representative Capacity, the only exclusive Right and Power to lay Taxes and Imposts upon the Inhabitants of this Colony”

But Henry didn’t stop there. He branded Parliament’s Stamp Act – and any similar attempt – as unconstitutional tyranny.

“And that every Attempt to vest such Power in any other Person or Persons whatever, than the General Assembly aforesaid, is illegal, unconstitutional and unjust, and have a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Liberty.”

This fifth resolution triggered the firestorm.

Here was not just a complaint about a tax, but a declaration that Parliament’s power was unconstitutional.

“IF THIS BE TREASON”

In the heated debate that followed, Patrick Henry delivered words that would echo through American history.

His biographer William Wirt captured what happened next.

“It was in the midst of this magnificent debate, while he was descanting on the tyranny of the obnoxious Act, that he exclaimed, in a voice of thunder, and with the look of a god, ‘Caesar had his Brutus – Charles the first, his Cromwell – and George the third – ‘”

The chamber erupted.

“’Treason,’ cried the Speaker – ‘treason, treason,’ echoed from every part of the House.”

What followed revealed the steel in Patrick Henry’s spine. With every eye in the chamber fixed on him, with cries of treason ringing in his ears, Henry could have backed down, apologized and retreated.

Instead, he doubled down.

“It was one of those trying moments which is decisive of character. – Henry faltered not an instant; but rising to a loftier attitude, and fixing on the Speaker an eye of the most determined fire, he finished his sentence with the firmest emphasis) ‘may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it.’”

No contemporary record of Henry’s speech exists. Wirt reconstructed the scene decades later from witness interviews. The exact words remain uncertain, but the impact was undeniable. Later testimony confirms that Henry delivered something extraordinary that day.

A twenty-two-year-old student named Thomas Jefferson witnessed the entire confrontation. Decades later, he would recall “torrents of sublime eloquence from mr Henry.”

Jefferson’s account reveals the political forces at work. Henry had his allies. “mr Henry moved, & Johnston seconded these resolutions successively.”

But arrayed against them stood Virginia’s establishment.

“They were opposed by Randolph, Bland, Pendleton, Nicholas, Wythe & all the old members whose influence in the house had, till then, been unbroken.”

The old guard versus the firebrand. Jefferson witnessed the climactic moment when the fifth resolution came to a vote.

The margin was razor-thin: “the last however, & strongest resolution was carried but by a single vote. the debate on it was most bloody.”

Jefferson, positioned outside the chamber, overheard the establishment’s dismay.

“I was then but a student, & was listening at the door of the lobby (for as yet there was no gallery) when Peyton Randolph, after the vote, came out of the house, and said, as he entered the lobby, ‘by god, I would have given 500. guineas for a single vote.’ for as this would have divided the house, the vote of Robinson, the Speaker, would have rejected the resolution”

Henry’s constitutional challenge survived by a single vote – the narrowest possible margin between colonial submission and the path to resistance..

THE ESTABLISHMENT STRIKES BACK – AND FAILS

Henry made a critical miscalculation. After passage of the five resolutions, he departed for home, believing his work was complete.

As noted by Red Hill Patrick Henry National Memorial, Virginia’s political establishment moved swiftly to undo his victory.

“The next day, under pressure from the governor and the Council, the House rescinded Henry’s fifth resolution and had it erased from the official journal. Virginia’s royal governor, Francis Fauquier, even prevented the publication of the four resolutions in the Virginia Gazette.”

The governor’s censorship extended even to the first four resolutions, which contained nothing more controversial than established English constitutional principles.

Censorship, however, proved ineffective against colonial information networks. The resolutions spread throughout the colonies despite official suppression.

Rhode Island incorporated the resolutions into their own Stamp Act resolves on September 15, 1765:

“That therefore the General Assembly of this Colony have in their Representative Capacity, the only exclusive Right to lay Taxes and Imposts upon the Inhabitants of this Colony: and that Every Attempt to vest such Power in any Person or Persons whatever other than the General Assembly aforesaid is unconstitutional, and hath a manifest Tendency to destroy the Liberties of the People of this Colony.”

The language was unmistakable – Henry’s allegedly expunged fifth resolution, reproduced almost word for word.

The question remained: how did Rhode Island obtain text that Virginia’s government had officially erased? Years later, William Wirt posed this question to Jefferson.

“These were obviously copied with a few slight variations from the Resolutions of Virginia, and retain the 5th resolution which was expunged here. But how did this 5th resolution get to Rhode Island, having been expunged from our Journals? – probably by a letter from George Johnston, or some other patriot in our house.”

The incident revealed the existence of an effective patriot communication network that rendered official censorship meaningless.

TOO DANGEROUS TO VOTE?

Henry’s sixth and seventh resolutions have no official record of being voted on – perhaps because they were far more radical than the fifth resolution that had already brought the House to the brink of chaos.

Henry’s sixth resolution struck at the heart of imperial authority – declaring that Virginians owed no obedience whatsoever to unconstitutional acts, articulating the foundational principle behind nullification.

“The Inhabitants of this Colony, are not bound to yield Obedience to any Law or Ordinance whatever, designed to impose any Taxation whatsoever upon them, other than the Laws or Ordinances of the General Assembly aforesaid.” [emphasis added]

The seventh resolution turned the tables. After being branded treasonous for challenging Parliamentary authority in the debate over the fifth resolution, Henry flipped the script – declaring that anyone who supported Parliamentary taxation was the real enemy of Virginia.

“That any Person who shall, by speaking, or writing, assert or maintain, that any Person or Persons, other than the General Assembly of this Colony, with such Consent as aforesaid, have any Right or Authority to lay or impose any Tax whatever on the Inhabitants thereof, shall be Deemed, AN ENEMY TO THIS HIS MAJESTY’S COLONY.”

Enemy of the colony. For supporting Parliament’s taxing power. Henry wasn’t playing games.

THE FIRE SPREADS

Virginia’s government may have suppressed the resolutions, but they couldn’t control what happened next. As Red Hill documents:

“Despite the attempt to suppress news of the legislature’s denunciation of the Stamp Act, within a few weeks versions of all seven of Henry’s resolutions were published in other colonies. As printed in Maryland, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and other colonies, Henry’s resolves articulated the principles of American rejection of Parliamentary authority.”

Colonial newspapers varied in their coverage – some printed four resolutions, others five or six, and only a few dared publish the radical seventh. The variations proved irrelevant.

The formal legislative record became meaningless. Despite only four resolutions being officially adopted, one rescinded, and two likely never receiving votes, the ideas themselves had escaped containment.

Patrick Henry’s resistance became Virginia’s resistance. Virginia’s resistance quickly became America’s resistance.

The impact was immediate and unmistakable. Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts observed how the Virginia Resolves changed everything.

“Nothing extravagant appeared in the papers till an account was received of the Virginia Resolves.”

Edmund Burke saw them as the spark for the resistance to the Stamp Act that led toward American independence.

Henry had accomplished something no colonial leader had managed before – turning local resistance into a continental movement.

HENRY’S FINAL WORD

Decades later, an aging Patrick Henry reflected on what he had unleashed that day in 1765. The young firebrand had become an elder statesman, and time had given him perspective on the forces he had set in motion. On the back of his personal copy of the Virginia Resolves, he traced the direct line from his resolutions to American independence:

“The alarm spread throughout America with astonishing quickness, and the Ministerial party were overwhelmed. The great point of resistance to British taxation was universally established in the colonies. This brought on the war which finally separated the two countries and gave independence to ours.”

But he understood that victory was only the beginning.

“Whether this will prove a blessing or a curse, will depend upon the use our people make of the blessings which a gracious God hath bestowed on us.”

Patrick Henry wasn’t finished. The man who had defied Parliament and sparked the Revolution ended with a warning that transcends time.

“If they are wise, they will be great and happy. If they are of a contrary character, they will be miserable. Righteousness alone can exalt them as a nation. Reader! whoever thou art, remember this; and in thy sphere practise virtue thyself, and encourage it in others.”