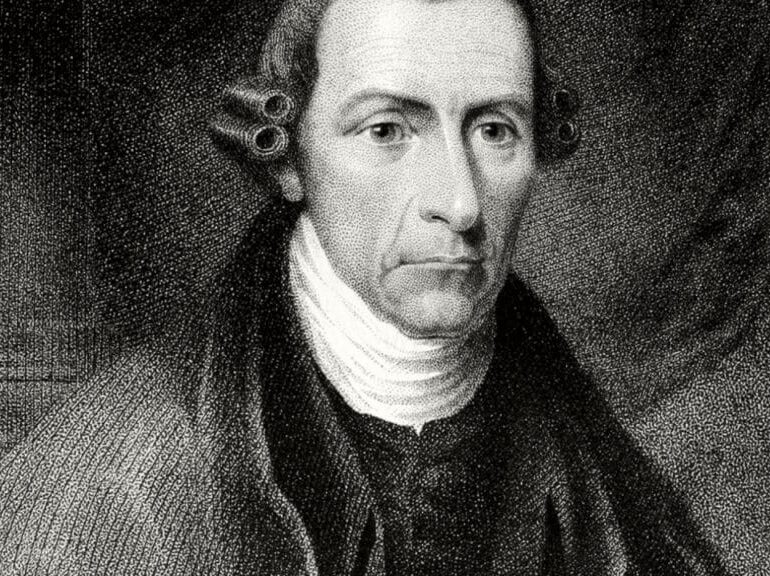

Patrick Henry Warns of a “Great and Mighty Empire”

By: TJ Martinell

On June 5, 1788, Patrick Henry gave a speech at the Virginia Ratifying Convention warning that “consolidation” – centralizing of power – would turn the United States into a dangerous empire.

The speech was prophetic, and if you didn’t know otherwise, you’d assume it was spoken by some modern political analyst.

The convention ran from June 2-22. Participants included James Madison, Edmund Randolph, John Marshall and George Mason. By June 7, Henry was arguing that the new federal government should not be ratified without a Bill of Rights attached to it guaranteeing certain liberties. Two days before that, he spoke on the many reservations he had regarding the proposed Constitution.

In a nutshell, Patrick’s primary fear was that the States would ultimately transition from a decentralized, voluntary confederation into a consolidated empire as the result of expansive federal power, a permanent standing army, and a strong executive branch.

One of the initial targets in his speech was the Constitution’s preamble, which reads, “We the people,” rather than the states. In actuality, this was done for simplicity’s sake, since it wasn’t known which states would ratify it and which ones wouldn’t. Also, constitutional preambles are not legally binding; they serve as expressions of intent, nothing more.

However, Henry viewed the change in the preamble’s language as a move toward centralizing authority:

“Is this a monarchy, like England — a compact between prince and people, with checks on the former to secure the liberty of the latter? Is this a confederacy, like Holland — an association of a number of independent states, each of which retains its individual sovereignty? It is not a democracy, wherein the people retain all their rights securely. Had these principles been adhered to, we should not have been brought to this alarming transition, from a confederacy to a consolidated government.” [Emphasis added]

Henry was also wary of the many new powers bestowed to the federal government. While Federalist supporters of ratification claimed the new general government would be limited in power, he was skeptical:

“We are told that we need not fear; because those in power, being our representatives, will not abuse the powers we put in their hands. I am not well versed in history, but I will submit to your recollection, whether liberty has been destroyed most often by the licentiousness of the people, or by the tyranny of rulers. I imagine, sir, you will find the balance on the side of tyranny.” [Emphasis added]

One of the most understated fears of the founders like Henry was the tyranny of a standing military force, which he adamantly believed would be the result of the new Constitution. While under the Articles of Confederation militia were controlled locally, the new government would have the ability to not only create its own army, but take control of local militia.

“My great objection to this government is, that it does not leave us the means of defending our rights, or of waging war against tyrants….Have we the means of resisting disciplined armies, when our only defence, the militia, is put into the hands of Congress?

“A standing army we shall have, also, to execute the execrable commands of tyranny; and how are you to punish them? Will you order them to be punished? Who shall obey these orders? Will your mace—bearer be a match for a disciplined regiment? In what situation are we to be? [Emphasis added]

Henry argues the inevitable result would be, like Rome, the transformation of a republic into an empire. Like all empires, it will need a permanent military force.

“If we admit this consolidated government, it will be because we like a great, splendid one. Some way or other we must be a great and mighty empire; we must have an army, and a navy, and a number of things.

If you make the citizens of this country agree to become the subjects of one great consolidated empire of America, your government will not have sufficient energy to keep them together. Such a government is incompatible with the genius of republicanism. There will be no checks, no real balances, in this government.” [Emphasis added]

At the Philadelphia Convention there was significant debate as to the role of the executive. Alexander Hamilton wanted the position to be for life, effectively a king. Even though it was brought down to a mere four-year term, Henry still warned that “your President may easily become king.”

Many of his apprehensions stemmed from the reality that the new government depended on, in his opinion, good men to serve in leadership for it to retain its limited powers.

“Show me that age and country where the rights and liberties of the people were placed on the sole chance of their rulers being good men, without a consequent loss of liberty! I say that the loss of that dearest privilege has ever followed, with absolute certainty, every such mad attempt.

“If your American chief be a man of ambition and abilities, how easy is it for him to render himself absolute! …. Away with your President! we shall have a king: the army will salute him monarch: your militia will leave you, and assist in making him king, and fight against you: and what have you to oppose this force? What will then become of you and your rights? Will not absolute despotism ensue? . . . [Emphasis added]

Proponents of the Constitution at the time highlighted the amendment process; if there were a problem with the new government, there was a way to address it. Yet, Henry saw the three-fourths requirement in both Congress and the states for any amendment to be enacted as a way to guarantee tyranny of the minority in stymieing reforms.

“A bare majority in these four small states may hinder the adoption of amendments; so that we may fairly and justly conclude that one twentieth part of the American people may prevent the removal of the most grievous inconveniences and oppression, by refusing to accede to amendments. Is this the spirit of republicanism?” [Emphasis added]

Before the Constitution was adopted, Henry warned that it would create a “great and mighty empire” headed by a president able to “render himself absolute,” backed by a long-standing army and aided by a Congress that usurped control of the local militia.

At the time, he may have seemed rather melodramatic. But to read those words today in 2022 makes it tempting to wonder if he somehow was given a glimpse into the future and spoke accordingly.