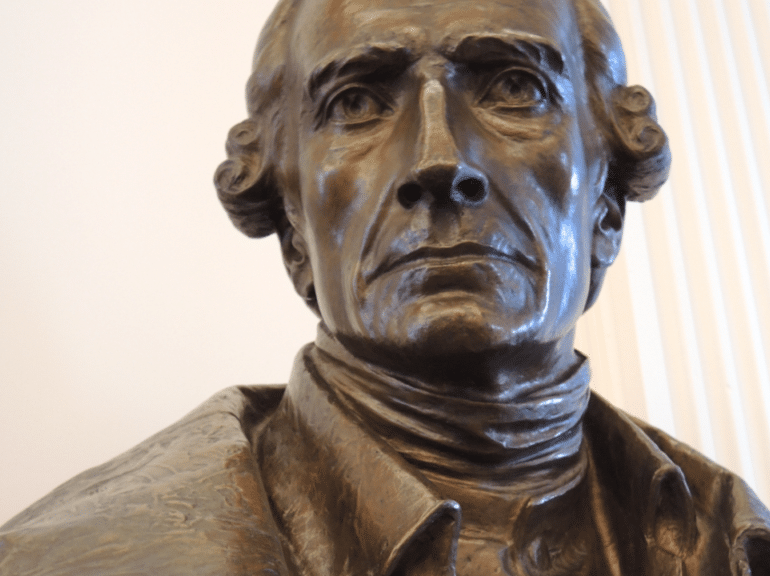

Patrick Henry Demands a Bill of Rights

By: TJ Martinell

On June 7, 1788, Patrick Henry delivered one of many long speeches at the Virginia Ratifying Convention, demanding the inclusion of a Bill of Rights in the proposed U.S. Constitution before its adoption.

The convention ran from June 2-22, and was significant in many regards. Among those attending with Henry included many prominent founding fathers including James Madison, Edmund Randolph, John Marshall and George Mason.

During the convention, the delegates examined and debated many concerns anti-federalists had about the proposed Constitution, which was seen by them as dangerously expanding the powers of the general government compared to the existing Articles of Confederation.

Federalists claimed that these new powers were needed to make the government effective, and that proper restraints were included to prevent the same tyranny they had recently overthrown.

While the supporters of the Constitution persuaded Randolph to vote in favor of ratification after he initially opposed it at the Philadelphia Convention, almost a week into it, Patrick Henry was still not satisfied by supporters’ reassurances. He insisted that they delay ratifying it until a Bill of Rights were included.

Richard Henry Lee made the same kind of effort the year prior, although his motion to include a Bill of Rights even before sending the Constitution to the states was rejected by the Confederation Congress.

Though others were pushing urgency in its adoption, Henry argued in a long, lengthy speech that the matters at stake mandated discretion.

“That government is no more than a choice among evils, is acknowledged by the most intelligent among mankind, and has been a standing maxim for ages,” he said. “If this be a truth, that its adoption may entail misery on the free people of this country, I then insist that rejection ought to follow. At present we have our liberties and privileges in our own hands. Let us not relinquish them. Let us not adopt this system till we see them secure.”

To hastily adopt the new constitution without properly determining its long-term consequences out of a false perception of emergency would be reckless, he added.

“We have the animating fortitude and persevering alacrity of republican men to carry us through misfortunes and calamities. It is the fortune of a republic to be able to withstand the stormy ocean of human vicissitudes. I know of no danger awaiting us. Public and private security are to be found here in the highest degree. Sir, it is the fortune of a free people not to be intimidated by imaginary dangers. Fear is the passion of slaves.”

One point of contention was whether the people themselves were dissatisfied with the Articles of Confederation. Federalists insisted it was weak and ineffective, while Henry felt otherwise:

“The middle and lower ranks of people have not those illuminated ideas which the well-born are so happily possessed of; they cannot so readily perceive latent objects. The microscopic eyes of modern statesmen can see abundance of defects in old systems; and their illuminated imaginations discover the necessity of a change. They are captivated by the parade of the number ten —the charms of the ten miles square. Sir, I fear this change will ultimately lead to our ruin. My fears are not the force of imagination; they are but too well founded. I tremble for my country; but, sir, I trust, I rely, and I am confident, that this political speculation has not taken so strong a hold of men’s minds as some would make us believe.”

A contention among the federalists was that a strong central government, rather than a weak confederation of states, was essential to republican form of government.

Henry cited Switzerland as proof that wasn’t the case:

“Switzerland consists of thirteen cantons expressly confederated for national defence. They have stood the shock of four hundred years; that country has enjoyed internal tranquillity most of that long period. Their dissensions have been, comparatively to those of other countries, very few. What has passed in the neighboring countries? War, dissensions, and intrigues; —Germany involved in the most deplorable civil war thirty years successively, continually convulsed with intestine divisions, and harassed by foreign wars! France, with her mighty monarchy, perpetually at war. Compare the peasants of Switzerland with those of any other mighty nation: you will find them far more happy: for one civil war among them, there have been five or six among other nations: their attachment to their country and freedom, their resolute intrepidity in their defence, the consequent security and happiness which they have enjoyed, and the respect and awe which these things produced in the bordering nations, have signalized those republicans. Their valor, sir, has been active; every thing that sets in motion the springs of the human heart engaged them to that protection of their inestimable privileges. They have not only secured their own liberty, but have been the arbiters of the fate of other people. Here, sir, contemplate the triumph of the republican governments over the pride of monarchy.”

Henry also viewed the new powers found in the proposed constitution as a threat to state’s rights as well as individual liberty – not just from domestic tyranny but foreign intrigue:

“Their (foreign nations) cheaper way, instead of laying out millions in making war upon you, will be to corrupt your senators. I know that, if they be not above all price, they may make a sacrifice of our commercial interests. They may advise your President to make a treaty that will not only sacrifice all your commercial interests, but throw prostrate your bill of rights. Does he fear that their ships will outnumber ours on the ocean, or that nations whose interest comes in contact with ours, in the progress of their guilt, will perpetrate the vilest expedients to exclude us from a participation in commercial advantages? Does he advise us, in order to avoid this evil, to adopt a Constitution, which will enable such nations to obtain their ends by the more easy mode of contaminating the principles of our senators? Sir, if our senators will not be corrupted, it will be because they will be good men, and not because the Constitution provides against corruption; for there is no real check secured in it, and the most abandoned and profligate acts may with impunity be committed by them.”

Henry’s objections didn’t derail ratification of the Constitution, but the convention did include a proposed Bill of Rights with its ratification documents later that month. A revised version was eventually adopted by the first Congress in the form of constitutional amendments that addressed issues such as freedom of speech, the right to keep and bear arms, and clarifying the limitations placed on the federal government.

The sad irony is that Henry’s warnings about the federal government have clearly come to pass, and that was even with a Bill of Rights. In other words, as alarmist as Henry may have seemed, he actually underestimated the damage to liberty that would be gradually unleashed in the years to come.