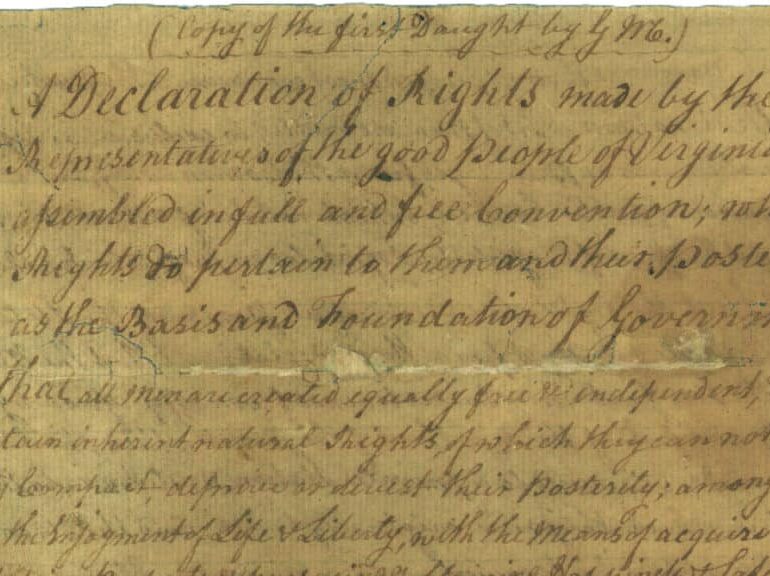

Setting a Foundation: The Virginia Declaration of Rights

By: Mike Maharrey

On June 12, 1776, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed the Virginia Declaration of Rights. It is arguably the most important founding document that most people have never heard of.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights laid the groundwork for both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Most significantly, the first three sections establish the philosophical framework that supports the entire U.S. system of government.

It declares that “all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights,” that “all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people,” and that “the community has an indubitable, inalienable, and indefeasible right to reform, alter, or abolish [government], in such manner as shall be judged most conducive to the public weal.”

These ideas were later reflected in the Declaration of Independence.

History

Months before the 13 colonies approved the Declaration of Independence, Virginia was already operating as a free and independent state. The colonial governor fled in January 1776 after the burning of Norfolk. In his absence, the Governor’s Council (the upper house of the colonial legislature) and the House of Burgesses dissolved themselves into a Convention under the authority “of the people” and assumed control over colonial affairs.

On May 15, 1776, the Convention declared Virginia a free and independent state “absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain. The resolutions included three action steps — drafting a declaration of rights, drafting a constitution, along with establishing confederated relationships with the other colonies and treaty relationships with other countries.

Historian Kevin Gutzman wrote that the entire process drew from precedents set during Britain’s Glorious Revolution.

“Self-consciously following the example of Britain’s Glorious Revolution, in which the Declaration of Rights had been the condition of William and Mary’s joint assumption of the English monarchy, the Virginians put their fundamental statement of political principles first, and then adopted the constitution that would implement it. Virginians thought of their colony as independent from that point.”

The Convention formed a committee headed by George Mason to draft the declaration of Rights.

Mason drew from and expanded on existing English political thought. A close reading of the declaration reveals influences including the English Bill of Rights (1689) and the writings of John Locke.

He begins by establishing the philosophical foundations of government, including separation of powers, and then outlines several specific individual rights, including many that were reflected in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights. The document affirms the right to a jury trial, protection from excessive fines and bail, a ban on general warrants that authorize searches without “facts,” freedom of the press, and the subordination of the militia to civil authority.

James Madison penned the final article, declaring that “religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.”

The Convention adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights on June 12, 1776.

Gutzman writes, “The influence of the Virginia Declaration of Rights would be hard to exaggerate.”

“Many of its provisions were used in other states. Thomas Jefferson, helping Frenchmen draft their Revolution’s Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, saw to it that some of the Virginia provisions were essentially translated into that document. From France, their language made its way into the charters of several francophone countries, and eventually into the United Nations’ version. From there, it would be transplanted into yet more countries’.”

A Revolution of Thought

In fact, the Virginia Declaration of Rights reflected a revolution in thought. It turned the established British conception of government on its head.

When people today talk about the American Revolution, they generally mean the fight with England. But there was a more fundamental revolution that began long before the first shot was fired and ultimately drove the American colonists to seek independence – a revolution of thought that radically altered the conception of sovereignty. The Virginia Declaration of Rights articulated these ideas.

In an 1818 letter to Hezekiah Niles, John Adams described the American Revolution in just such terms.

“But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American war? The Revolution was effected before the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people; a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations. … This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments, and affections of the people, was the real American Revolution.”

This fundamental change in thought relates to the concept of sovereignty – the question of who holds the ultimate power and authority within a political society.

In the British system, the “King in Parliament” was considered sovereign. In effect, Parliament was sovereign with the king serving as the arm to put its power into action.

In the years leading up to the Revolution, Americans started to question this conception of political power. They began to think of a constitution as something that exists above the government. The colonists began to reject the idea that government formed the constitution and instead conceived of the constitution as something that binds government. They used these kinds of constitutional arguments when challenging British authority, asserting they had longstanding, well-established constitutional rights that the King and Parliament were violating.

We see this shift in the first several articles of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, particularly Section 2, declaring:

“That all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people; that magistrates are their trustees and servants and at all times amenable to them.”

This was reflected in the Declaration of Independence.

“To secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Declaration of Rights makes clear the importance of firmly stating our principles and placing limits on government. The question then becomes, how do you enforce them?