The ideas that formed the Constitution: Vattel and the Law of Nations

By: Rob Natelson

Within the Constitution’s text are meanings most purported constitutional experts never see. They fail to see those meanings because they don’t take the trouble to learn enough about the environment in which the Constitution arose.

Suppose you’re reading a novel in which a character says, “I dug that.” If the novel was published last year and has a contemporaneous setting, the character probably means he made a hole in the ground. But if the novel was published in 1973 or describes events around that time—particularly if the character is young and hip—then he may well mean, “I liked that” or “I understood that.”

The Constitution was written 236 years ago. Its English is not 21st-century English, but the language of 1787. Moreover, its words aren’t to be read as if they appeared in a novel or a cookbook. They are to be read as components of an 18th-century legal document, the “supreme Law of the Land.”

You may have heard someone say the Constitution was written to be understood by ordinary people. That’s mostly true—but it’s true only in context. Most of the framers and leading ratifiers were lawyers, and the “ordinary people” they addressed were members of the American public during the late 1780s. That was a time in which the general public was far more conversant with law and policy than the public is today.

I don’t want to suggest that understanding the Constitution is an exercise in obscurantism, performable only by a few experts. On the contrary, understanding the document is well within the abilities of the average literate American. But as is true with any specialized writing, you do have to acquire some background.

Many of the Constitution’s expressions were “terms of art” derived from 18th-century law. In other words, they carried specific legal meanings. Sometimes, as in the case of “the Writ of Habeas Corpus” (Article I, Section 9, Clause 2), the legal nature of the term is obvious. Yet there are other words and phrases that look ordinary and innocent, but were intended to convey specialized meanings. Two illustrations are “necessary” in the Necessary and Proper Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 18) (pdf) and “the freedom of speech” in the First Amendment.

The Constitution’s legal terms are explained in my book “The Original Constitution: What It Actually Said and Meant.”

The Law of Nations

Legal terms of art also appear in what constitutional lawyers call the “Define and Punish Clause” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 10). This provision gives Congress power to “define and punish Offenses … against the Law of Nations.”

“The law of nations” was the usual 18th-century term for international law. “Nations” included not only sovereign countries, but also non-citizen, foreign ethnic groups within sovereign territories. The “Law of Nations” consisted of standards governing international conduct. To “define and punish Offenses” meant to enforce those standards against people who would violate them. The Define and Punish Clause empowers Congress to adopt laws punishing people who violate a treaty, assault an ambassador, cross an international boundary without permission, and so forth.

The Define and Punish Clause is one of several of the Constitution’s references to foreign policy and international relations. This essay tells you more about them.

The Founders’ Sources of International Law

During the 17th and 18th centuries, five great scholars forged international law into its modern shape. In 1783, the Confederation Congress empaneled a committee consisting of James Madison of Virginia, Thomas Mifflin of Pennsylvania, and Hugh Williamson of North Carolina—all of whom were to serve at the 1787 Constitutional Convention. This committee recommended that Congress purchase the works of all five international law scholars.

The first of these scholars was Huigh DeGroot (1583–1645), more commonly known by his Latin name: Hugo Grotius. He published the “Law of Nature and Nations” in 1625.

For several years Grotius held high office in the Netherlands. But like Jean-Louis DeLolme, the subject of our last installment, he got cross-wise with the power structure. He was imprisoned, broke out of prison, and relocated to France. He continued his career of writing and diplomacy. Today Grotius is recognized as the father of modern international law.

The other four authors were Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–1694) and Christian Wolff (1679–1754) (both Germans), Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui (1694–1748), a professor at the University of Geneva, and Burlamaqui’s most famous student, Emer de Vattel (1714–1767). (Vattel’s first name sometimes is rendered erroneously as “Emmerich.”)

To the Founders, these men formed an international law pantheon. American lawyers and judges regularly relied on Grotius, Pufendorf, Burlamaqui, and Vattel, and, more rarely, on Wolff. Most of the five surfaced during the 1787–1790 constitutional debates. I documented some of their appearances in a recent article for the British Journal of American Legal Studies (pdf).

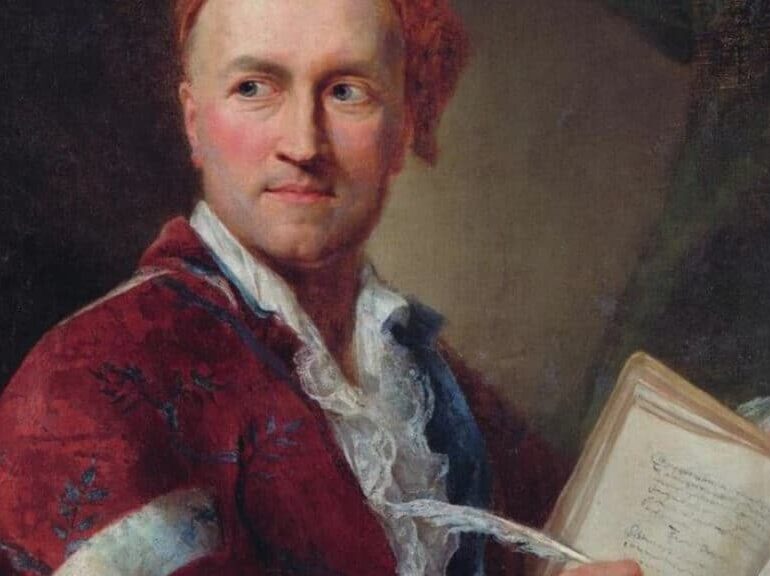

Emer de Vattel

Of the five, the one the American Founders most frequently consulted was Vattel. Like Grotius, Vattel was both a scholar and diplomat. His principal work, “Le Droit des Gens” (“The Law of Nations”), was published in French in 1758 and translated into English two years later. You can learn more about Vattel’s life at the Online Library of Liberty.

There were four reasons why Vattel was so congenial to the American Founders: First, he was the most recent of the five great authorities. Second, his book was comprehensive and readable. Third, he was a strong advocate for individual liberty. And fourth, he discussed issues that, while not always part of the “law of nations,” were very important to the Founders: the nature of confederations, the superiority of constitutions to legislatures, the need for one and only one person to supervise the executive branch, and so forth.

Vattel was referenced at the Constitutional Convention, primarily in a speech by Luther Martin of Maryland. He also showed up during the ratification debates. For example, at the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, James Wilson argued about Vattel with an Antifederalist delegate. In the South Carolina legislature, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney also debated Vattel with an Antifederalist. In New York, Gov. George Clinton relied on Vattel in a speech to his state’s ratifying convention.

Why These Five Great Authorities Matter

We must consult the Founders’ international law authorities to fully understand the Constitution’s international law terms. Here are a few examples:

- The Constitution says a state may not enter into a treaty. But with congressional consent a state may enter into an interstate compact. What is the difference?

- The Constitution refers to “Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls.” What exactly are these officials, and how do they differ?

- Some writers wonder where Congress derives its power to regulate immigration. The Founders’ international law authorities tell us that it’s part of the power to “define and punish Offenses … against the Law of Nations.” (See my Aug. 29, 2022, Epoch Times essay for more information.)

- The Constitution also grants Congress power to “declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal …” When must Congress declare war, and when is such a declaration unnecessary? What are “Letters of Marque and Reprisal?” The Founders’ international law authorities answer these questions as well.

- The president is the nation’s leader on foreign policy issues. Commentators sometimes complain that the Constitution’s list of presidential foreign affairs powers seems skimpy. But the Founders’ international law authorities tell us the list is much fuller than it first appears. For instance, the power to “receive Ambassadors” also includes the prerogative of refusing to see them and of bestowing, or refusing, recognition of foreign governments.

The works of these authors are available on the internet. Vattel in particular is useful to anyone who wants to know more about our Constitution.