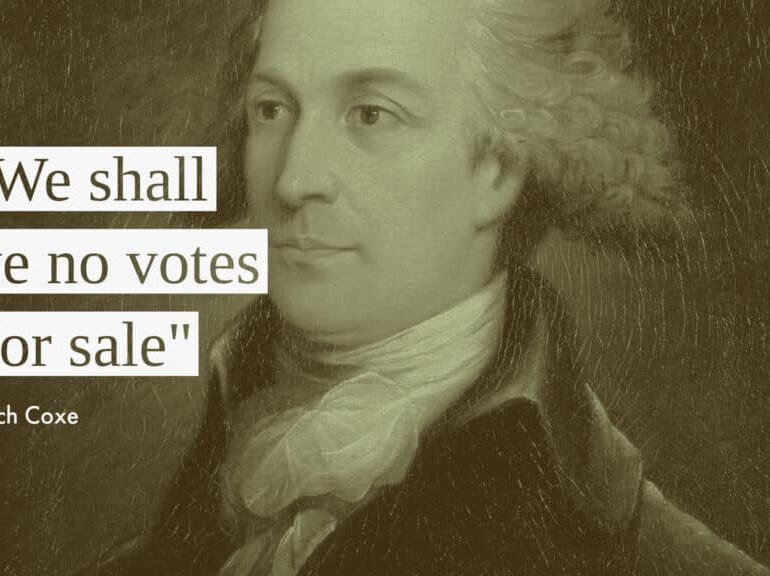

Tench Coxe Defends the Structure of the House of Representatives

By: Mike Maharrey

Countering Anti-Federalist fears that Congress wouldn’t represent the diverse interests of the American population, Tench Coxe came out swinging, insisting that the House would be “the immediate delegates of the people” and calling it a “popular assembly.”

He made his case in his third essay of An American Citizen, as he examined the “nature and powers” of the House of Representatives by contrasting it with the British House of Commons.

A common Anti-Federalist concern was the number of Representatives in the House. They repeatedly warned that it would be too small to properly and accurately represent the people.

For example, George Mason wrote, “In the House of Representatives there is not the substance but the shadow only of representation; which can never produce proper information in the legislature, or inspire confidence in the people; the laws will therefore be generally made by men little concerned in, and unacquainted with their effects and consequences.”

Coxe kicked off his defense of the House against this kind of attack asserting that it would be a “truly popular assembly” with each member representing about 30,000 people and chosen by 6,000 “enlightened and independent freemen.” (The vast majority of people weren’t eligible to vote.)

As such, the representatives would be accountable to a wide variety of people, both rich and poor. This relatively large number of electors for each representative would make it difficult to “bribe” those voters, or as Coxe put it, “No decayed and venal borough will have an unjust share in their determinations.”

Furthermore, under the proposed system, “No old Sarum will send thither a Representative by the voice of a single elector. As we shall have no royal ministries to purchase votes, so we shall have no votes for sale. For the suffrages of six thousand enlightened and independent freemen are above all price.”

Old Sarum was a special constituency in Great Britain with an extremely small electorate that was vastly over-represented in Parliament.

Coxe also noted that as the House grew in size, the number of members could be limited so the body wouldn’t become too unwieldy.

“When the increasing population of the country shall render the body too large at the rate of one member for every thirty thousand persons, they will be returned at the greater rate of one for every forty or fifty thousand, which will render the electors still more incorruptible.”

With the Apportionment Act of 1911, Congress fixed the number of representatives in the House at 435. Today, that gives a ratio of representatives to people of about 1 to 700,000.

But this was exactly what many Anti-Federalists feared – that the number of Representatives in the House would be too small to properly and accurately represent the people.

For example, in his third paper, Brutus asserted, “The house of assembly, which is intended as a representation of the people of America, will not, nor cannot, in the nature of things, be a proper one—sixty-five men cannot be found in the United States, who hold the sentiments, possess the feelings, or are acqainted with the wants and interests of this vast country.”

Coxe was apparently unconcerned about having a small number of representatives, as long as they were chosen by a large enough number of electors to prevent corruption.

Coxe went on to argue that, as is the case with senators, the requirements for representatives would put a check on the corruption, seen as inherent in the British lower house.

He pointed out that the House of Commons was filled with “military and civil officers and pensioners” known as placemen, who could vote in their self-interest or the interest of their government agency.

Unlike parliamentarians, Members of the House have constitutionally limited authority.

“They cannot make new offices for themselves, nor increase, for their own benefit, the emoluments of old ones, by which the people will be exempted from needless additions to the public expenses on such sordid and mercenary principles.”

Furthermore, members of the House of Commons were elected every seven years. Coxe said the shorter terms for members of the House would offer more security to the people.

“With us no placemen can sit among the Representatives of the people, and two years are the constitutional term of their existence.”

Coxe also argued that setting the minimum age for membership in the House at 25 would help prevent “an undeserving, unqualified or inexperienced youth” from getting into office.

“At twenty-one a young man is made the guardian of his own interests, but he cannot for a few years more be entrusted with the affairs of the nation.” [Emphasis original]

Coxe believed other qualifications would make for more suitable representation. For instance, the Constitution requires all representatives to be an inhabitant of the state that elects them. This makes them “intimately acquainted with their particular circumstances.”

Coxe then noted several differences between the House and the Senate.

While the Senate has the power to try impeachments, the House, “possess the sole and uncontrollable power of impeachment.”

And the House would “have a negative upon every legislative act of the other house.”

Most significantly, the House holds the power of the purse.

“Without their consent no monies can be obtained, no armies raised, no navies provided. They alone can originate bills for drawing forth the revenues of the Union.”

Coxe summed up his analysis by pointing out that the people would ultimately control the House and that would serve as a check on other branches as well.

“In short, as the sphere of federal jurisdiction extends, they will be controllable only by the people, and in contentions with the other branch, so far as they shall be right, they must ever finally prevail.”

This, he noted, would help achieve the goals of “peace, liberty and safety.”

The takeaway one might get from that is that the people themselves failed to control the power of the House and Senate. Coxe makes this argument more clear in his final American Citizen essay, where he notes, “The people will remain, under the proposed constitution, the fountain of power and public honor.”

There, he also discussed a number of “further securities for the safety and happiness of the people,” including the separation of powers between the federal and state governments. We’ll cover that in the final installment of this series.