The Treaty of Paris: How the War for Independence Almost Didn’t End

By: Michael Boldin

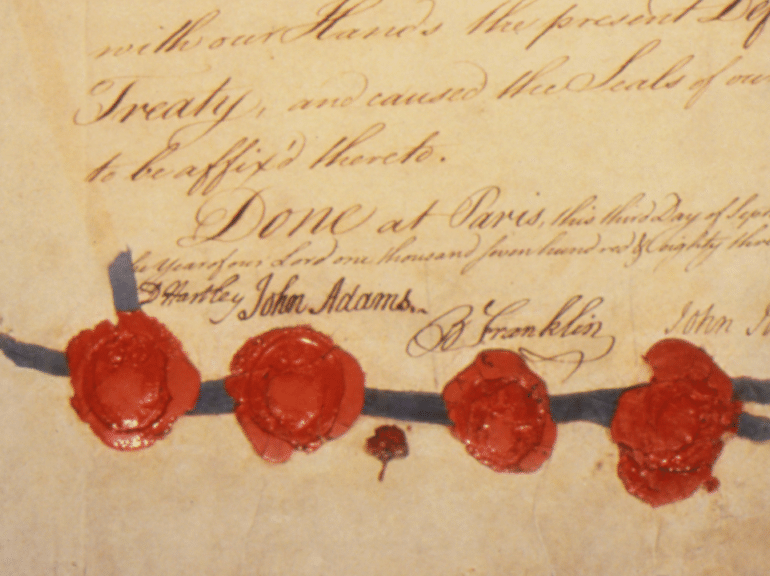

Signed on Sept 3, 1783 – the Treaty of Paris has long been called the formal end to the War for Independence. But the war didn’t officially end on that date with the signatures of Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay.

The treaty, made with 13 free, sovereign, and independent states, still needed their approval according to the rules of the Articles of Confederation, and it almost didn’t happen. This forgotten history reveals the true nature of the system as understood by the Founders and Old Revolutionaries.

INDEPENDENCE

The starting point of this story is with the Declaration of Independence, which established “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES.”

Free and independent states. That’s plural.

As Mike Maharrey points out, “The colonies declared their independence from Great Britain as 13 independent, sovereign states.”

Unfortunately today, most people look at the word “state” as some kind of political subdivision of a larger nation, but this wasn’t the case in 1783. Maharrey continued, noting that state and nation were synonymous in this context, “When they declared independence, Georgia and New York placed themselves on equal footing with England and Spain. And the Declaration also referred to the ‘State of Great Britain.’”

Back to the Declaration, where Jefferson and co. continued with this:

“as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do.”

Writing to Gen. Washington on July 6, 1776, John Hancock affirmed this view:

“The Congress have judged it necessary to dissolve the Connection between Great Britain and the American Colonies, and to declare them free & independent States.”

THE TREATY

We see the same principle included in the treaty of Paris – officially titled The Definitive Treaty of Peace Between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United States of America. Here, from the very first sentence of Article I of the treaty:

“His Brittanic Majesty acknowledges the said United States, viz., New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, to be free sovereign and Independent States”

Joe Wolverton emphasized the importance of this, writing, “Notice, moreover, he is not signing a treaty with one nation; he is signing a treaty with 13 nations, each of which is listed at the beginning of Article 1.”

Article 5 of the Treaty also tells us about the relative status of the Congress in relationship to the states comprising that confederation:

“Congress shall earnestly recommend it to the Legislatures of the respective States to provide for the Restitution of all Estates, Rights, and Properties, which have been confiscated belonging to real British Subjects”

Notice how the Congress is only empowered to RECOMMEND to the state legislatures that they restore property, but the decision is actually up to the states, not Congress.

Wolverton continued, noting that “next, in Article 7 peace is explicitly declared between ‘his Britannic Majesty and the said states.’ The states are now at peace with Britain, if Congress is able to convince the state legislatures to agree to the terms.” [emphasis added]

This point is essential.

ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION

While most people look to the signing of the Treaty on Sept 3, 1783 as formally ending the war, this is historically and factually false. It still needed to be approved by at least 9 states, and that wasn’t an easy thing to get done in 1783-84. In fact, it went down to the wire and almost didn’t happen!

First, from the Articles of Confederation, Article IX:

“The united states, in congress assembled, shall never engage in a war, nor grant letters of marque and reprisal in time of peace, nor enter into any treaties or alliances …

unless nine states assent to the same” [emphasis added]

Delegates from the several states were called to assemble in Annapolis, Maryland – then serving as the capital – in Nov 1783. Because the Treaty itself stipulated that it be approved and returned to England within six months of being signed – the deadline being Feb 3, 1784 – time was of the essence.

NOT ENOUGH STATES

However, it was a full six weeks before there were enough representatives from the states to call a quorum and conduct business. But that was just 7 of the 13 states, not the 9 needed to approve the Treaty.

Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina had full delegations in Annapolis. Only one representative from New Hampshire and South Carolina was present. No one was there from New York, New Jersey, Connecticut or Georgia.

There were multiple roll calls in December and into January. And as the deadline drew closer, all they could do was wait – and plead.

None of the absent states responded to a Congressional appeal on Dec. 23 that “the safety, honor, and good faith of the United States” required their immediate presence in Congress. Thomas Mifflin, president of Congress, sent a letter to the Governors of New Jersey and Connecticut informing them that the Treaty deadline would not be met without the votes of their states.

Neither responded.

Weather was a serious problem as the Winter of 1783-84 was one of the worst recorded at the time. Thomas Jefferson described it as “severe beyond all memory.” It brought the longest stretch of sub-zero temperatures to New England, froze over the Chesapeake Bay, where the capital was situated, and made roads nearly impassable all over.

Morristown, NJ was hit with over 80 inches of snow, temps dove down to -20 in Hartford, and ice closed down the harbors in both Philadelphia and Baltimore.

There was serious concern that the British would use a missed deadline as a reason to renegotiate the terms, or even restart the war. The Continental Army had mostly disbanded and the British still occupied forts on the frontier. This was recognized by all as a dangerous situation.

JEFFERSON LEADS

So some in Congress started pushing a more desperate approach. That is, ratify the Treaty with just the 7 states present, rather than the 9 required by the Constitution. This is the old familiar approach of politicians – ignore the rules given to them because of an “emergency.”

Sure sounds familiar, doesn’t it? But it’s nothing new in American history either.

Thomas Jefferson, for one – was vehemently opposed to such a move. He explained why, noting that the British had obviously read and understood the American Constitution – the Articles of Confederation – and recognized that they would object to an illegal ratification of the Treaty. He wrote, “they knew our constitution, and would object to a ratification by 7.”

It appears that some had suggested trying to ratify with just 7, but keep it a secret, and Jefferson rejected that as well:

“if that circumstance was kept back, it would be known hereafter, & would give them ground to deny the validity of a ratification into which they should have been surprised and cheated, and it would be a dishonorable prostitution of our seal”

In short – never give your opponents any legal wiggle room. And never take any steps beyond the limits of the Constitution, even in an “emergency” situation. Once you do, you’ve established the precedent for more and more. And more.

Jefferson was chosen to head a committee comprising members of both factions and proposed a compromise. Rather than violating the Articles of Confederation, or lying to the British about it, he suggested they do something that sounds pretty radical in today’s political world – tell the truth.

Congress, Jefferson recommended, could pass a resolution affirming that the seven states present were all on board in favor of ratification of the treaty, but they had a disagreement as to the competency of Congress to ratify with only seven states. They would send that to Europe and request an additional 3 months.

It was still risky, but it was agreed that Congress would hold a vote on this proposal on Jan 14, 1784 – less than a month before the deadline.

DOWN TO THE WIRE

Meanwhile, express riders left Annapolis for the states to inform governors of the pending vote. And President Mifflin sent his aide Col. Josiah Harmar to New Jersey to plead for attendance. He also ordered him to stop in Philadelphia to press Richard Beresford, a delegate from South Carolina, to leave his sick bed and show up in Annapolis for the vote.

In a spectacular turn of events, on Jan 13, the night before the vote, Connecticut delegates James Wadsworth and Roger Sherman and New Jersey’s John Beatty arrived in Annapolis.

Congress was only one state away from the 9 needed. The next morning, Beresford arrived to complete South Carolina’s delegation, eliminating the need for the compromise resolution.

On Jan 14, 1784 Congress unanimously ratified the treaty with nine votes from Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.

That date is the real formal end of the War for Independence.