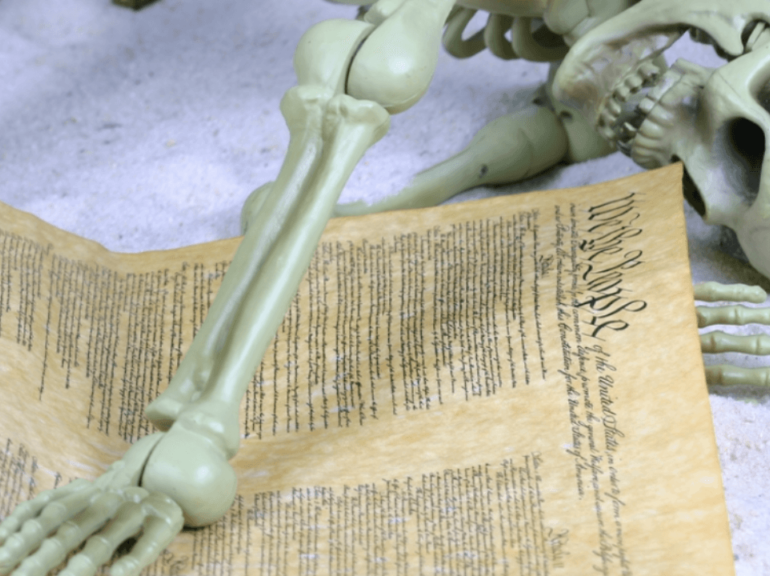

Did the Constitution Fail the People? Or Did the People Fail the Constitution?

By: Mike Maharrey

Did the Constitution fail?

A lot of people think it did. This popular quote by Lysander Spooner sums up the thoughts of many.

“But whether the Constitution really be one thing, or another, this much is certain – that it has either authorized such a government as we have had, or has been powerless to prevent it. In either case it is unfit to exist.”

Arguing against ratification of the Constitution, Brutus wrote:

“Constitutions are not so necessary to regulate the conduct of good rulers as to restrain that of bad ones.”

It’s pretty easy to see that didn’t happen. The bad ones have expanded federal government power decade after decade to the point that we now live under the largest government in history. It’s understandable for some people to conclude that the Constitution failed in its primary aim.

But asking whether the constitution failed is actually the wrong question. To find out the source of the problem, we need to dig a little deeper.

John Dickinson was known as “the Penman of the Revolution” and was the primary author of the first draft of the Articles of Confederation. Writing under the penname Fabius in support of ratification of the Constitution, he wrote:

“A good constitution promotes, but not always produces a good administration.” [Emphasis added]

Dickinson’s position was that a good constitution is the starting point. It makes it more difficult for the government to violate your liberty. But that doesn’t mean it will always play out that way. You can’t just rely on the document itself. You need something more to ensure “a good administration.”

James Madison made the same point in Federalist #48 when he warned of the inadequacy of “parchment barriers.”

“A mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments, is not a sufficient guard against those encroachments which lead to a tyrannical concentration of all the powers of government in the same hands.”

In other words, you can’t just write words on paper and expect them to keep government from centralizing and consolidating power.

Gouverneur Morris was a key figure in the drafting of the Constitution. Writing in his diary years later, he expressed a similar sentiment, observing that “considerate men are not dupes of patriotic professions.”

“Neither will they confide the defence of their liberty to paper bulwarks.”

He went on to assert that such men never believed that amendments (the Bill of Rights) gave any additional security to life, liberty, or property.

Discussing peace negotiations with the British in 1782, John Jay also warned against parchment barriers. And he alludes to what we really need to keep governments in check.

“He thought an explicit acknowledgment of our independence in treaty very necessary, in order to prevent our being exposed to further claims. I told him we should always have arms in our hands to answer those claims; that I considered mere paper fortifications as of but little consequence.” [emphasis added]

All of these founding-era figures observed that you can’t depend on mere words written on paper to stop people with power from exercising or expanding power.

Securing Our Rights

The Declaration of Independence asserted that the purpose of government is to “secure our rights.”

“That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Given that we live under the largest government in history and it violates our rights on a daily basis, it’s difficult to argue that we are a free people. In practice, we are a people begging on our knees for permission to be free. Our current situation proves that the government created by the Constitution utterly failed in its most basic role.

But given the warnings of these and many others in the founding generation, we shouldn’t be shocked at the failure of parchment barriers.

St. George Tucker wrote the first systematic commentary on the U.S. Constitution. In View of the Constitution of the United States, he pointed out that “all governments have a natural tendency towards an increase. and assumption of power.” He also observed that “the administration of the federal government has too frequently demonstrated that the people of America are not exempt from this vice in their constitution.”

“We have seen that parchment chains are not sufficient to correct this unhappy propensity.”

If words on paper won’t restrain government, how can government be restrained?

As Madison put it in Federalist #48, “some more adequate defense is indispensably necessary.” In other words, somebody has to enforce the parchment barriers.

In Federalist #46, Madison gave us the blueprint. In a nutshell, resist the overreaching power.

In practical terms, Madison called for “a refusal to cooperate with officers of the union.” He said if people in even one state did this, it would create “very serious impediments.” And if people in several states acted together, Madison said it would “create obstructions which the federal government would be hardly willing to encounter.”

Thomas Jefferson echoed this spirit of resistance in A Summary View of the Rights of British America, saying, “A free people claim their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate.”

As already mentioned, many people use Spooner’s “whether the Constitution be one thing or another” quote to highlight the failure of the document. But in his A Defense for Fugitive Slaves, Spooner outlined the same basic strategy for enforcing the Constitution as Madison and others in the founding generation. He argued that the “right and the physical power of the people to resist injustice” are the only security they have for their liberties.

“Practically no government knows any limit to its power but the endurance of the people.”

He also asserted that “the right of the people, therefore, to resist an unconstitutional law, is absolute and unqualified, from the moment the law is enacted.”

As Roger Sherman argued during the ratification debates, no bill of rights, or any document for that matter, “ever yet bound the supreme power longer than the honey moon of a new married couple, unless the rulers were interested in preserving the rights.”

The key is to make it “in their interest” to preserve the rights by resisting them every time they cross the line – from the very moment they cross the line. As Dickinson put it in opposition to the Townshend Acts in 1767, we must “oppose a disease at its beginning.” Or as John Adams later put it, “Nip the shoots of arbitrary power in the bud, is the only maxim which can ever preserve the liberties of any people.”

It is up to the people to love liberty, to demand it, to fight for it whether the government people want us to or not.

That brings us back to Dickinson who argued it ultimately comes down to the “supreme sovereignty of the people.”

We have the final authority and responsibility.

“It is their duty to watch, and their right to take care, that the Constitution be preserved; or in the Roman phrase on perilous occasions – to provide that the Republic receive no damage.”

So, if the Constitution wasn’t preserved, was it the document that failed to limit itself? Or was it a failure of the people to take human action to restrict the actions of government?

Based on the founders, the old revolutionaries, and even Spooner, it was the latter.

A lesser-known supporter of the Constitution writing under the pseudonym State Soldier argued that there is nothing in the Constitution itself that “particularly bargains for a surrender of your liberties.”

“It must be your own faults if you become enslaved. Men in power may usurp authorities under any constitution — and those they govern may oppose their tyranny.” [Emphasis added.]

George Washington made a similar observation, saying “if their Citizens should not be completely free & happy, the fault will be entirely their own.”

This dovetails with Spooner’s view.

“The exercise of the right is neither rebellion against the constitution, nor revolution—it is a maintenance of the constitution itself, by keeping the government within the constitution. It is also a defence of the natural rights of the people, against robbers and trespassers, who attempt to set up their own personal authority and power, in opposition to those of the constitution and people, which they were appointed to administer.”

On Sept 17, 1787, the day the Constitution was signed by delegates at the Philadelphia Convention, Benjamin Franklin delivered a speech. His words were eerily prophetic.

“In these sentiments, Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults, if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us, and there is no form of Government but what may be a blessing to the people if well administered, and believe farther that this is likely to be well administered for a course of years, and can only end in Despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall become so corrupted as to need despotic Government, being incapable of any other.”

Franklin knew the government created by the Constitution would fail — not because of any structural defect. He said that the Constitution would be “well administered for a course of years.” But he predicted it would go off the rails because the people would not do their job in keeping that government within its limits. At they point, they would become incapable of operating under anything other than despotism.

The Constitution didn’t fail us. We failed the Constitution.