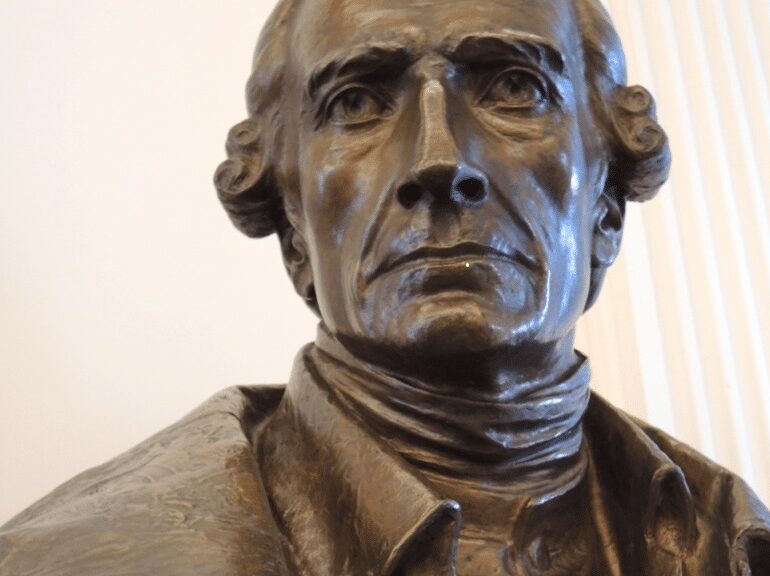

Patrick Henry’s Lesson on the Need for a Bill of Rights

By: TJ Martinell

On June 12, 1788, Patrick Henry spoke during the Virginia Ratifying Convention, reiterating the need for a Bill of Rights in the proposed U.S. Constitution before its adoption. During this speech, he offered a history lesson highlighting the importance of preserving freedom, but he also warned that written guarantees are, by themselves, ineffective.

The debate over the Bill of Rights was more nuanced than one might think. While Federalists touting the Constitution argued that the scope of the general government it would create was limited, anti-federalists were reluctant to grant a general government such powers, especially the power of taxation.

Many prominent people in the debates were actually opposed to the inclusion of a bill of rights. They believed that offering explicit guarantees for certain liberties would infer that any rights absent from it would not be protected. (These concerns were addressed in the Ninth and Tenth Amendments to alleviate those fears.)

But Henry was a persistent critic of the Constitution at the Virginia Ratifying Convention because it lacked a bill of rights.

Even though Henry had already pitched the idea of a Bill of Rights a week before, on June 12 he pressed his argument further.

“I am that the dangers of this system are real, when those who have no similar interests with the people of this country are to legislate for us — when our dearest interests are left in the power of those whose advantage it may be to infringe them.

“….The tyranny of Philadelphia may be like the tyranny of George III. I believe this similitude will be incontestably proved before we conclude.”

Federalists insisted that the powers of the government were “few and defined,” as James Madison put it in Federalist #45. Therefore, the argument went, the Constitution did not require explicit guarantees in a bill of rights, because such powers weren’t delegated in the first place.

Henry argued that English history proved otherwise.

“I am sorry to bring forth hackneyed observations. But, sir, important truths lose nothing of their validity or weight, by frequency of repetition. The English history is frequently recurred to by gentlemen. Let us advert to the conduct of the people of that country. The people of England lived without a declaration of rights till the war in the time of Charles I. That king made usurpations upon the rights of the people. Those rights were, in a great measure, before that time undefined. Power and privilege then depended on implication and logical discussion. Though the declaration of rights was obtained from that king, his usurpations cost him his life. The limits between the liberty of the people, and the prerogative of the king, were still not clearly defined.

Here, Henry was referencing the Petition of Right (1628) during the reign of Charles I, which set out some individual protections against the state. But, he noted, those rights continued to be violated.

“The rights of the people continued to be violated till the Stuart family was banished, in the year 1688. The people of England magnanimously defended their rights, banished the tyrant, and prescribed to William, Prince of Orange, by the bill of rights, on what terms he should reign; and this bill of rights put an end to all construction and implication. Before this, sir, the situation of the public liberty of England was dreadful. For upwards of a century, the nation was involved in every kind of calamity, till the bill of rights put an end to all, by defining the rights of the people, and limiting the king’s prerogative.” [Emphasis added]

In other words, once a clearly-defined Bill of Rights was passed in 1689, things finally improved for the liberties of the people.

He further stated that “when we see men of such talents and learning compelled to use their utmost abilities to convince themselves that there is no danger, is it not sufficient to make us tremble? Is it not sufficient to fill the minds of the ignorant part of men with fear? If gentlemen believe that the apprehensions of men will be quieted, they are mistaken, since our best informed men are in doubt with respect to the security of our rights.”

While Henry would ultimately prevail in his demands for a bill of rights, the irony is that his opponents who opposed a bill of rights turned out to be vindicated as well. A legal doctrine known as Incorporation born out of the 14th Amendment has enabled the federal judiciary to weaponize the Bill of Rights against decentralized authority, effectively undermining the Ninth and Tenth Amendments as ratified in 1791.

Henry’s history lesson about the lack of an English Bill of Rights was correct. But we can extract our own history lesson from Henry’s era: no matter what is written down on paper, those looking to usurp power and circumvent limited government powers will eventually find a way to misinterpret them. Thus, governments and their officials can’t be expected to restrict themselves.

Fundamentally, the people must always be ready to nullify acts of tyranny when people in power refuse to abide by written guarantees.