Why Facts Don’t Matter to People

by Barry Brownstein – AIER

Frustrated with COVID-19 restrictions on daily life, a friend said to me, “I just want to know the truth.”

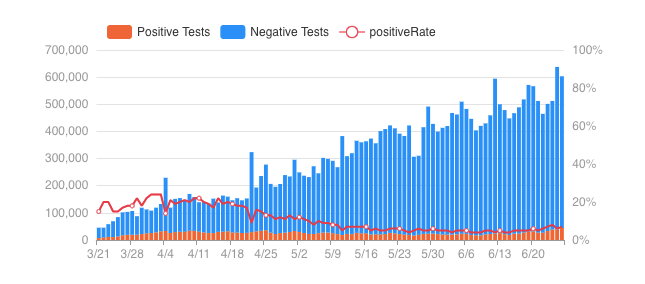

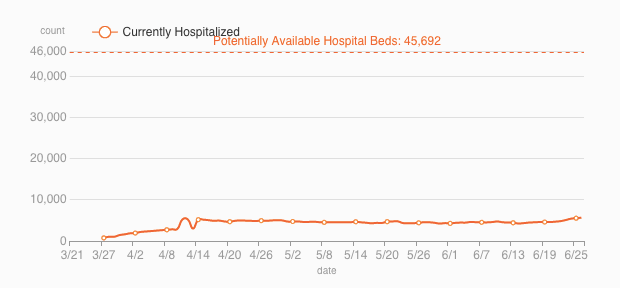

Like many people, my exasperated friend, and others I know, are mesmerized and frightened by daily news reports on the number of COVID-19 cases. You can cite all the data you want, such as these from the U.S.:

It’s good news all around. But you turn on the television and get a different message. People worry about sending their children to school this fall. Some display authoritarian views as they excuse politicians for destructive errors merely because they showed “strong leadership.”

If you’re wondering why so many people don’t see the world the way you do, engage them in conversation. You will find they are as well-intentioned as you are, but they are looking in a different direction. Beneath their opinions and fears, beliefs are shaping how they see the world.

Because of different beliefs, your villains may be their heroes. They may look at the world of effects while you are looking at causes. They’re hoping a better leader comes to power, while you’re considering how the presidency became so powerful and destructive.

Until their beliefs change, they will never consider how politicians and experts with too much power turned a pandemic into a catastrophe. As Einstein put it, “Whether you can observe a thing or not depends on the theory which you use. It is theory which decides what can be observed.”

The “clear guidance” politicians claim to dispense and “the truth” my friend wants to learn are not rooted in the principles of human flourishing. My friend is waiting for a government official to blow the all-clear whistle. My friend doesn’t want to believe experts are as fallible as he is, and that the prevailing scientific consensus may be false. For me to explain to him why “defining risk is an exercise in power” would bring a blank stare of disbelief.

When the Only Truth is the Leaders’

In her book, Without You, There is No Us, Suki Kim tells the story of teaching English to elite all-male students at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology in North Korea. Kim, who was born and raised in Seoul, immigrated to America with her family when she was 13.

In her classroom in North Korea, conservations were furtive. Any out of line words could cause deportation for an instructor. The consequences of open discussion were far worse for students; imprisonment in one of North Korea’s death camps or execution awaited a student with counterrevolutionary ideas.

Yet, there were encounters over meals at the University where some candor occurred.

One day, a student asked Kim what she thought of “The Song of General Kim-Jong-il.” The song was an unofficial national anthem of North Korea and paid homage to the current North Korean despots’ father.

Lyrics of this ditty include: “All blossom on this earth tell of his love, broad and warm…The protector of righteousness he is…Brilliant and beloved is the name of our General.”

Suki Kim couldn’t share her genuine feelings about the song, so she uttered vague words of respect.

The student then asked how the American system of government worked. We pass laws, she said, when the president and Congress “work with one another.”

Kim’s student was incredulous. “I think the president is the one who should make decisions. He has the power, no?” This student had grown up in a society where only one view could be voiced. “Thinking was dangerous,” Kim writes. Even for Kim, “it sometimes felt as though ‘I’ did not exist,” which led her to experience “deeply claustrophobic and sometimes almost unbearable” feelings.

Students did fervently believe lies, such as North Korea is the “most powerful and prosperous [nation] on the planet.” They constantly lied too about basic facts of their daily lives. Kim writes, “Lying and secrecy were all they had ever known.” She asks, “In a country where the government invents its own truth, how could they be expected to do otherwise?”

Kim was at a crossroads for further conversation with her student. Was the student a spy trying to trap her, or even worse, would the student end up in the gulag for merely discussing the limits of power? Kim responded, “Our country is not for the president but for the people. The president is just the face, the symbol, but the real power belongs to the people. The people make the decisions.”

If only what Kim said was true. Have you noticed how many Americans are thinking like North Koreans? They seem reassured and relieved when their favorite politicians behave like North Korean despots issuing “field guidance.”

When North Korean despot Kim Jong-un visits a factory or farm, he makes pronouncements for improvements. Such pronouncements are called “field guidance” or “on-the-spot guidance.” No matter how nonsensical, the pronouncements of the despot are revered and obeyed.

In North Korea, there is no path forward that doesn’t begin with 100% obedience. There is nothing to be discovered, only edicts to obey. To serve the despot is the only purpose of life for North Koreans.

Andrew Cuomo is a beloved politician, despite having issued “field guidance” sending thousands of nursing home residents to their deaths. Even in May, after news of his disastrous nursing home orders were widely available, his approval rating was at 81%.

Today, voices in opposition to the field guidance of politicians and experts are still being heard. But don’t take this for granted; tolerance for communicating opposing views is shrinking.

A March 2020 poll of Americans with 3,000 respondents showed strong bipartisan support for criminalizing speech. About 70% of those surveyed supported government “restricting people’s ability to say things” deemed as misinformation. Nearly 80% endorsed the conscription of health care professionals. Government seizure of businesses and property was supported by 58%. Over 70% supported the detention of COVID-19 patients in government facilities. The majority of those surveyed did not change their opinion even when told their views may violate the Constitution.

Often Facts Don’t Matter

It is tempting to present more facts to those who don’t see the world the way you do. Yet, we have all experienced the truth of John Kenneth Galbraith’s famous observation: “Faced with a choice between changing one’s mind and proving there is no need to do so, almost everyone gets busy with the proof.”

Due to confirmation bias, “we embrace information that confirms [our] view while ignoring, or rejecting, information that casts doubt on it.” Those who believe that experts and politicians should lead the way will not question their belief no matter what alternative COVID-19 data is presented.

In his article “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises,” psychology professor Raymond Nickerson observes that a “significant fraction of the disputes, altercations, and misunderstandings that occur among individuals, groups, and nations,” is due to confirmation bias.

In short, to get through to your friend, you must overcome the human tendency to filter and ignore evidence.

Uncover Beliefs

If facts won’t convince others, what’s left? Instead of facts, consider helping to uncover beliefs that are driving confirmation bias.

A common mistaken belief, invisible to a believer, is that individuals can be trusted with unchecked power. Driven by that unexamined belief, some focus on getting the “right” individuals into power.

John Adams wrote: “There is danger from all men. The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty.”

With this principle of liberty in mind, bring into your conversations the idea that all humans are fallible. Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Trump, Governor Cuomo, and all the rest are fallible. Politicians or “experts are not angels. Individuals, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot be counted on to know or do the right thing.

In Federalist Paper No. 48, Madison warned, “A mere demarcation on parchment of the constitutional limits of the several departments, is not a sufficient guard against those encroachments which lead to a tyrannical concentration of all the powers of government in the same hands.”

Rights wherein viability varies depending upon how people feel are not rights at all. Such rights are empty promises, quickly withdrawn by authoritarian politicians.

In her book The Girl with Seven Names North Korean defector Hyeonseo Lee reflected on why basic human rights are absent in North Korea:

“I started thinking deeply about human rights. One of the main reasons that distinctions between oppressor and victim are blurred in North Korea is that no one there has any concept of rights. To know that your rights are being abused, or that you are abusing someone else’s, you first have to know that you have them, and what they are.”

Like North Koreans, many Americans don’t know the natural rights they have and so do not know when their rights are being violated.

The frightened believe some politician or expert must decide COVID-19 policy. They see no other way to deal with the threat and experience more order.

Read Hayek’s famous observation about order, replacing the words “that in complex conditions” with the words “during a pandemic:” “To the naive mind that conceives of order only as the product of deliberate arrangement, it may seem absurd that in complex conditions [during a pandemic], order and adaptation to the unknown can be achieved more effectively by decentralizing decisions.”

With that simple substitution, we expose a core belief shared by many Americans. They believe centralizing decision-making is effective in unknown, complex conditions and they want their politicians to do something. Like Dr. Fauci, they believe the path forward is obedience.

If major league baseball is played this summer, games will be in empty outdoor stadiums. Despite the low risk, Dr. Fauci recently felt compelled to interject himself in contentious negotiations to issue field guidance on when the baseball season should end. Will better outcomes come from following Fauci’s field guidance or from decentralized decision-making based on what Hayek calls “the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place?” Your answer depends on your belief system.

COVID-19 has forced many of our well-intentioned friends into what some call liminal space—“a space where you have left something behind, yet you are not yet fully in something else.” In such a space, old beliefs are questioned, and new beliefs have not yet formed.

Those who have entered such a space don’t need more facts; they are probably exhausted processing the ephemeral, self-proclaimed “truths” of politicians and experts. Before introducing more facts, engage a friend in conversation to uncover and point to the eternal truth of liberty.