When is the real Independence Day: July 2 or July 4?

by Scott Bomboy of the National Constitution Center

There’s no doubt the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence in July 1776. But which date has the legitimate claim on Independence Day: July 2 or July 4?

If John Adams were alive today, he would tell you July 2. Other Founders would say July 4, the day that is currently recognized as a federal holiday by our national government. And still, other Founders would say, “what Independence Day?” since the holiday wasn’t widely celebrated until many of the Founders had passed away.

Here is the evidence, so you can decide which Independence Day is the real Independence Day!

Officially, the Continental Congress declared its freedom from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when it voted to approve a resolution submitted by delegate Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, declaring “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

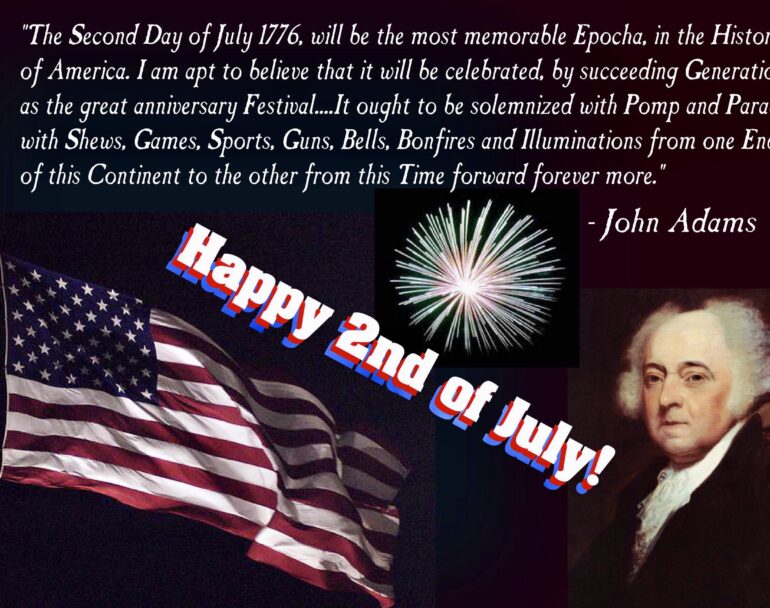

John Adams thought July 2 would be marked as a national holiday for generations to come:

“[Independence Day] will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival… It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this continent to the other from this Time forward forever more,” Adams wrote.

After voting on independence on July 2, the Continental Congress then needed to draft a document explaining the move to the public. It had been proposed in draft form by the Committee of Five (John Adams, Roger Sherman, Robert Livingston, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson) and it took two days for the Congress to agree on the edits.

Once the Congress approved the actual Declaration of Independence document on July 4, it ordered that it be sent to a printer named John Dunlap. About 200 copies of the “Dunlap Broadside” version of the document were printed, with John Hancock’s name printed at the bottom. Today, 26 copies remain.

That is why the Declaration has the words, “IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776,” at its top, because that is the day the approved version was signed in Philadelphia.

On July 8, 1776, Colonel John Nixon of Philadelphia read a printed Declaration of Independence to the public for the first time on what is now called Independence Square.

(Most of the members of the Continental Congress signed a version of the Declaration on August 2, 1776, in Philadelphia. The names of the signers were released publicly in early 1777.)

The late historian Pauline Maier said in her 1997 book, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence, that no member of Congress recalled in early July 1777 that it had been almost a year since they declared their freedom from the British. They finally remembered the event on July 3, 1777, and July 4 became the day that seemed to make sense for celebrating independence.

Maier also said that arguments over the how to celebrate the Declaration arose between the Federalists (of John Adams) and the Republicans (of Thomas Jefferson) and that the Declaration and its anniversary day weren’t widely celebrated until the Federalists faded away from the political scene after 1812.

In an 1826 letter – the last he ever wrote — Thomas Jefferson spoke of the importance of Independence Day. “For ourselves, let the annual return of this day forever refresh our recollections of these rights, and an undiminished devotion to them,” he said.

Jefferson and Adams both passed away two days later, on the Fourth of July.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.