WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT AUTOMATIC LICENSE PLATE READERS

Automatic license plate reader technology is unregulated in Massachusetts (and in Ohio)—and it implicates civil liberties.

What is an automatic license plate reader?

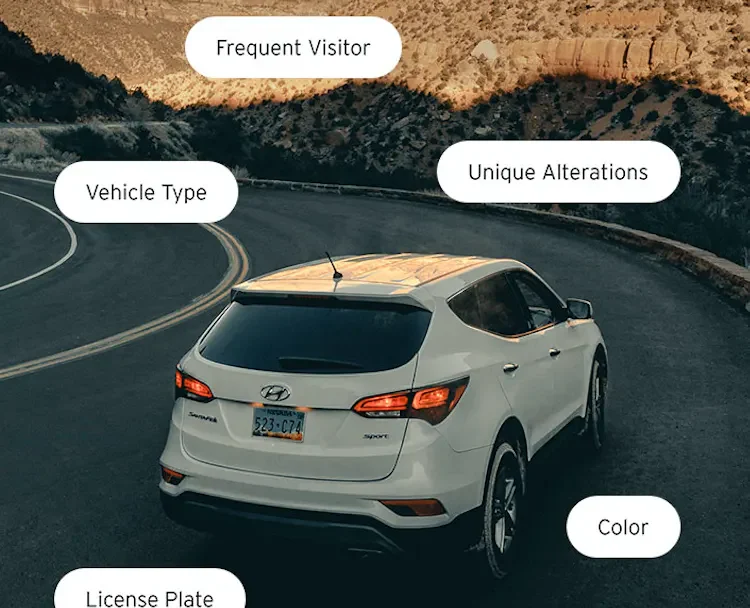

Automatic license plate readers (“ALPR”) enable private companies and government agencies to keep track of where people drive and when. The technology uses special cameras that are either mounted to stationary locations like traffic lights or affixed to moveable objects like cars and trucks. These cameras capture images of license plates and convert them to text files using optical character recognition technology. The original image, text file, and associated metadata such as date, time, and geographic coordinates are then added to a database. These databases are used by private industries like insurance, towing, and repossession to locate cars and perform investigations. They are also used by police departments to conduct dragnet surveillance of motorists.

How do police use license plate readers?

Police primarily use ALPRs in two ways: to track cars in real time and to track the past locations of cars. When police seek to find a particular car in real time, they can add information about that car to an ALPR list maintained by their department or another agency. These lists, sometimes called “vehicle of interest” lists or “hot lists,” are generated, aggregated, and shared by agencies like local police departments, the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, and more. The lists can include stolen cars, cars associated with Amber Alerts, and other vehicles of interest to police. When a car on one of these lists passes by a license plate reader, it generates an alert, also known as a “hit.” Depending on how an ALPR system is configured, a hit notification can be sent to an individual police officer or entire department for follow-up action.

Automatic license plate readers are also used to track the past locations of vehicles, enabling dragnet surveillance of millions of people. Police departments and intelligence agencies can access stored ALPR data dating back years in government and private company databases. One private company, Vigilant Solutions, boasts that its license plate reader database has billions of records of motorists’ movements, collected from states across the country. Police can pay to access these records on a subscription basis. Police can also collect their own ALPR data, which they can share with other government agencies and even private companies.

(Flock, Inc. the ALPR provider used by West Chester Township, only keeps records for 30 days unless an extended retention contract is subscribed to)

Some states have passed laws limiting how long police can retain license plate reader data and how they can share it and use it.

In Massachusetts, lawmakers have filed ALPR legislation for many years, but to date, the technology remains entirely unregulated at the state level.

Why should I be concerned about police use of license plate readers?

This technology impacts several civil liberties—from freedom of expression and association to freedom from unfettered surveillance, from protecting the privacy of people seeking abortion care in Massachusetts to defending the rights of immigrants across the country. In recent years, for example:

- The Virginia state police used license plate readers to track people’s attendance at political events;

- The New York Police Department used license plate readers to keep track of who visited certain places of worship, and how often;

- Federal immigration authorities bought license plate reader data and used it to track immigrants across the country.

The need for the public to have detailed information regarding this technology has become even more important after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade. With several states banning or severely limiting abortion, ALPR technology now poses a greater privacy threat. Police and private individuals in some states may seek location data showing people traveling to Massachusetts for reproductive care in order to use that evidence for civil and criminal penalties.

Despite all this surveillance, ALPR technology has been repeatedly shown to be unreliable; like other police technologies, ALPRs can and do make mistakes. Use of ALPRs by law enforcement across the country has been tainted with high error rates and improper identification of purportedly stolen vehicles. On multiple occasions, people have been traumatized after police pulled guns on them at traffic stops, relying on faulty data from license plate reader systems. Here in Massachusetts, the use of the technology has been marred by years of inaccurate timestamp data.

Is this technology regulated?

There is currently no statute in Massachusetts (or in Ohio) regulating police use of ALPRs.

In 2020, the state Supreme Judicial Court recognized that Massachusetts’ use of this technology could implicate constitutional protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. Specifically, the court noted that “[w]ith enough cameras in enough locations, the historic location data from an ALPR system in Massachusetts would invade a reasonable expectation of privacy and would constitute a search for constitutional purposes.”

In December 2022, the ACLU filed a public records lawsuit against the Massachusetts Executive Office of Public Safety and Security and the Department of Criminal Justice Information Services to obtain information about the state’s ALPR programs.