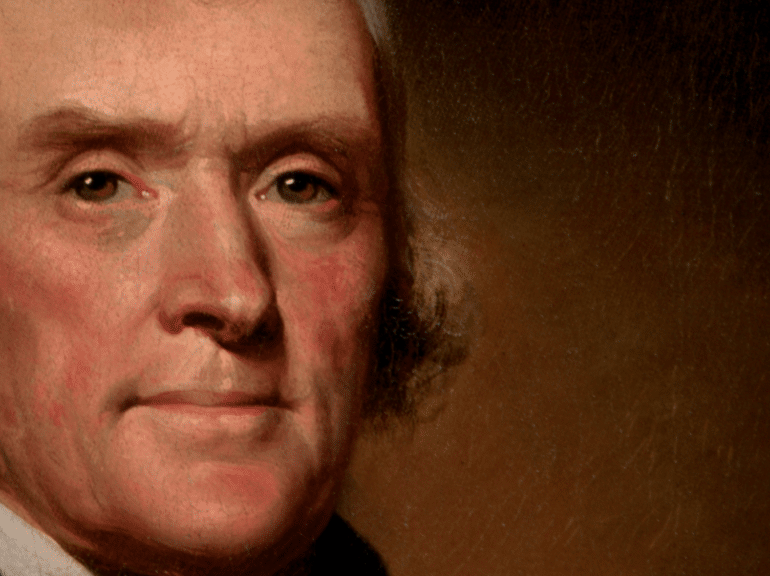

Thomas Jefferson’s Blueprint for Dealing With the National Debt

The way Thomas Jefferson handled the national debt should serve as a blueprint today. But instead, modern presidents look more like college students on a spending spree with their first credit cards.

When Donald Trump took office in January 2017, he inherited $19.95 trillion federal debt. He handed over a $27.75 trillion debt to Joe Biden. In just four years, the Trump administration added $7.8 trillion to the debt. Within eight months, Biden had added another $680 billion to the total.

But this isn’t just a Trump/Biden problem. Every modern president inherited a huge national debt and managed to expand it during their time in office. In fact, since 1940, every successive presidential administration has spent more than the previous administration in inflation-adjusted dollars.

But there was a time when some presidents took paying off Uncle Sam’s debts seriously. For instance, Thomas Jefferson faced a huge national debt when he took office in 1800. But unlike his modern counterparts, he didn’t grow it further. In fact, he significantly whittled down the debt.

Jefferson and his fellow Democrat-Republicans in Congress knocked about $26 million ($420,8 million in 2018 dollars) off the debt through his two terms in office — this despite taking on an additional $13 million of added debt for the Louisiana Purchase.

How did they do it?

Well, it was pretty simple. They cut spending and applied the savings toward paying down debt.

Jefferson summed up his budget policy in a letter to Elbridge Gerry in 1799, writing:

“I am for a government rigorously frugal and simple, applying all the possible savings of the public revenue to the discharge of the national debt and not for a multiplication of officers & salaries merely to make partizans, & for increasing, by every device, the public debt, on the principle of it’s being a public blessing.”

Despite facing a number of contingencies, Jefferson limited federal spending, keeping total outlays flat at between $8 and $10 million throughout his presidency.

The Democrat-Republicans held costs down by cutting the federal bureaucracy. And they even managed to do this with a federal workforce totaling just 130 employees.

There wasn’t a whole lot of fat to slice, so Jefferson went to part of the budget where the money was being spent – the military. He argued that funding a standing army in peacetime was a colossal waste of money. In his first message to Congress, Jefferson wrote:

“Sound principles will not justify our taxing the industry of our fellow citizens to accumulate treasure for wars to happen we know not when, and which might not perhaps happen but from the temptations offered by that treasure.”

Congress responded to Jefferson’s message, reducing the army to 3,000 soldiers and 172 officers. It also cut the navy to six frigates and reduced the number of foreign embassies to only three — in Britain, France, and Spain.

All of these spending cuts freed up about $7 million in revenue annually. Secretary of Treasury Albert Gallatin used the surplus to pay down the debt.

At the same time, Congress even reduced taxes, eliminating the hated whiskey tax, along with other internal taxes.

During Jefferson’s tenure, the federal debt fell from $83 million in 1801 to $57 million in 1809. As Chris Edwards at the Cato Institute noted, the drop in debt was impressive, especially considering that the government swallowed that $13 million of added debt from the Louisiana Purchase.

Jefferson was also the beneficiary of a growing economy. After falling in the first two years of his first term, primarily due to the tax cuts, federal revenues soared to nearly $17 million by the end of his presidency. This was largely a function of a huge increase in import duties. Instead of using growing revenue to increase the size and scope of the federal government, Jefferson and Gallatin applied the surplus to pay down the debt.

There’s a basic lesson here. If you want to reduce debt, you have to make government smaller. As Jefferson wrote to Lafayette in 1823:

“A rigid economy of the public contributions and absolute interdiction of all useless expenses will go far towards keeping the government honest and unoppressive.”