The Lesson of Newburgh

Two hundred and forty years ago this week, a group of officers of the Continental Army gathered in Newburgh, New York. The officers—relatively youthful men, many of them with their professional lives still ahead—had fought for seven years against the military might of the British Empire. On the Virginia Peninsula a year and a half earlier, they defeated Earl Cornwallis and his army at the Battle of Yorktown. Their fame spread across the world. Now forever a part of one of the great fighting forces of the age, the men of the Continental Army might have met in Newburgh to celebrate their exploits.

But instead, the soldiers were angry. Some were downright furious.

The Continental Congress, the erstwhile government of the newly independent United States, had been slow (even negligent) in paying the army. As a cost-saving measure, Congress stopped paying the army in 1782. The guarantee of life pensions, offered by Congress during the Revolutionary War to keep officers in the army, was nowhere to be found.

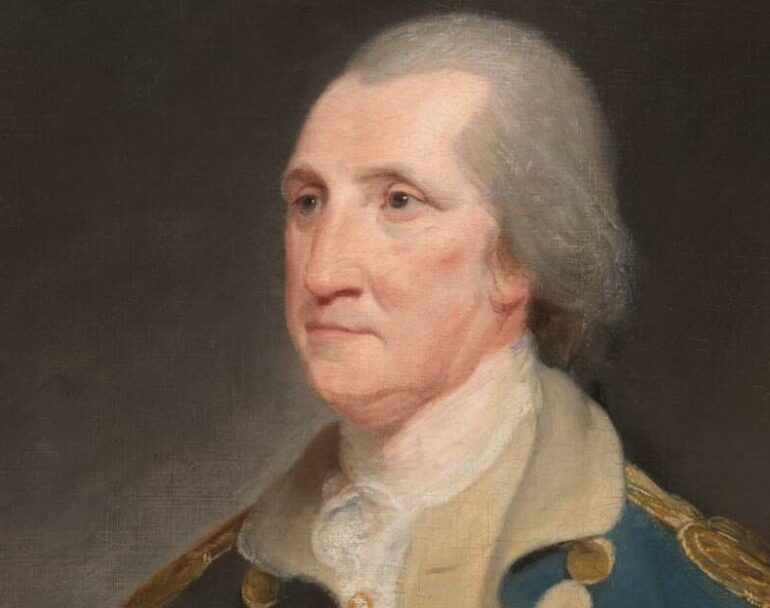

A group of officers, enraged at the perceived shameful treatment of the army by Congress, began preparing ways to find redress. Without informing the army’s high command, they circulated an unsigned letter urging a meeting at Newburgh in March 1783, ostensibly to discuss a range of possibilities including marching on Congress. George Washington caught wind of the meeting, which he called irregular and disorderly. He ordered the officers to a second meeting, overseen by a high-ranking officer. He also ordered a written report of the meeting, hinting that he himself would not attend.

When the second meeting occurred on March 15, the resentful and fuming officers were stunned when Washington himself appeared and asked to speak. Washington understood the officers’ frustrations but rebuked any attempt to coerce the civilian government with military force. Anyone “who wickedly attempts to open the floodgates of civil discord and deluge our rising empire in blood” should, he demanded, be opposed by the army. Coups, Washington made clear, would not only never be instigated by his army, they would also be opposed by the army. The civilian government of the United States must be protected, even when it acted inconsistently or imprudently.

After speaking, Washington took a letter out from a member of Congress of his pocket. He looked at it for a moment and held it uneasily. Slowly, he pulled his reading glasses from the pocket and haltingly put them on. Most of the soldiers had never seen Washington wear them. “Gentlemen,” Washington said gently, “you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.” The sight of a greying and aging Washington—loyal to the government as ever—shamed the conspirators, many of whom began to openly weep. The Newburgh Conspiracy was dead, and so was the first major threat to civilian government in the new republic.

The legacy of the Newburgh Conspiracy is often treated as a part of Washington’s personal legacy, and for good reason. Washington’s actions between 1781 and when he became President in 1789 prepared the way for constitutional government and the maintenance of civilian leadership throughout American history. Washington’s good example, however, was not the last word on the question of the military’s relationship to politics. While Americans have elected generals to high office since the eighteenth century, they have simultaneously retained a sense of caution regarding military men.

Following Washington, it took three decades before the next general made a serious bid for the presidency: Andrew Jackson. Political opponents, and even some of his supporters, had concerns over the elevation of a general to the chief executive. Henry Clay asked, somewhat sarcastically, if killing 2,500 British soldiers meaningfully qualified someone for the presidency. William Henry Harrison’s record was scrutinized when he ran in 1840, not only for being a military general but for being a general without a significant victory to his name. When Zachary Taylor ran in 1848, his surrogates argued that his lack of political experience made him a superior candidate (Taylor claimed to never have voted before because soldiers had to be above politics).

The generals elected to the White House in the Early Republic understood the tension between the enduring civilian government and the military’s subordination to that civilian government. Few ever appeared in uniform unless they were speaking to veterans, and even then, most chose to wear the black broadcloth suits of a civilian.

When Jackson assumed the presidency in 1829, he walked to the capitol in his inaugural parade with a few aged Revolutionary War veterans. William Henry Harrison included a few military units, mainly for their bands. Zachary Taylor’s inauguration appeared decidedly unmilitary, despite him only being a few months out of the army.

The militarization of American society became more pronounced after the Civil War, and that continued into the twentieth century. The mass volunteer mobilizations and the unpopular but enduring draft imposed by the federal government of the United States during the Civil War made the army a fact of life for more men and women than it had ever been before: 2.2 million men served in the Union army. This represented a massive percentage of men under arms, given the North’s 1861 population of 31 million. The war’s conclusion saw parades in Washington DC of the victorious Federal Army. Those parades were far and away the largest military celebrations held in the United States to date. The Grand Army of the Republic became a major fraternal organization. By 1890, its membership peaked at half a million men.

The process repeated itself in the aftermath of World War I and more particularly after World War II. The era of total war militarized societies in ways the Founding Fathers could not have imagined. The military’s raw size in manpower numbers meant that most men of military age by 1950 had some experience with at least one of the United States’ armed services. Armies performed political and societal purposes in ways they never had before. Military service became a marker of basic civic participation. Blue star and gold star families marked their losses publicly.

Military service was so synonymous with basic civic participation that candidates for office made it a foundational aspect of their public service. Every president from Harry Truman to George H. W. Bush had some active duty military experience. Whereas in the Early Republic, military service was regarded with suspicion, by the middle of the twentieth century, it was seen as normative and even necessary. The eighteenth-century republic’s fears regarding professional soldiers, standing armies, and their intrusiveness into civilian politics gave way to an expectation of and even comfort with military men at the helm of civic and political life in the United States.

Generals became more ubiquitous in political life, and so did the military’s presence in civil religion. Dwight Eisenhower’s election brought a general to the presidency for the first time in sixty years. But as President Eisenhower meticulously delineated the civilian government from the military. He never appeared in uniform and was careful not to staff the government with too many military men.

Eisenhower in fact became suspicious of the ties between the military and both American politics and the economy. In his farewell address in January 1961, Eisenhower warned of the emerging military-industrial complex. Few in power heeded the general’s admonition. Since the Cold War, policing, federal and state politics, infrastructure maintenance, and even research have seen an increased presence of the American military. Civic activities at professional sporting events are completely dominated by the presence of military imagery and often time military personnel.

Candidates for office in both parties regularly tout their military service as evidence of their ability to “lead” in their campaigns for higher office. This disposition to give governance over to the military has been particularly pronounced on the American right in the era of Donald Trump, who made a point of including an outsized number of generals in his administration. Trump quickly learned that American generals and soldiers, even those who serve politicians after their retirement, are often uncomfortable with partisan politics.

The lesson of Washington at Newburgh is not, however, simply that generals and soldiers should not be partisan. The lesson is that military men are not necessary or even preferable for the maintenance of a republican society. The American constitution and the republic it governs do not need “leaders”—they need citizens. The continued preference and often fawning partiality American voters show military men are not the fault of dutiful veterans who run for office, but it nonetheless feeds a broader political and cultural vice whereby Americans treat military men as uniquely suited to govern them. Indeed, no less a military man than Dwight Eisenhower saw society’s militarization as deeply problematic.

So, while we appreciate the American military and its role in maintaining the liberties of the United States when necessary, we might also look to Washington and remind ourselves that we don’t need the military in politics. Our history of appreciating military men is worth keeping. So too is our history of suspicion about their broader role in politics and society.