Northwest Ordinance: Landmark 1787 Law Set the Foundation

By: Mike Maharrey

On July 13, 1787, the Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, one of the most important and influential acts of the early republic. It established a bill of rights years before one was added to the Constitution, and prohibited slavery in the territory decades before the 13th Amendment was added to the Constitution.

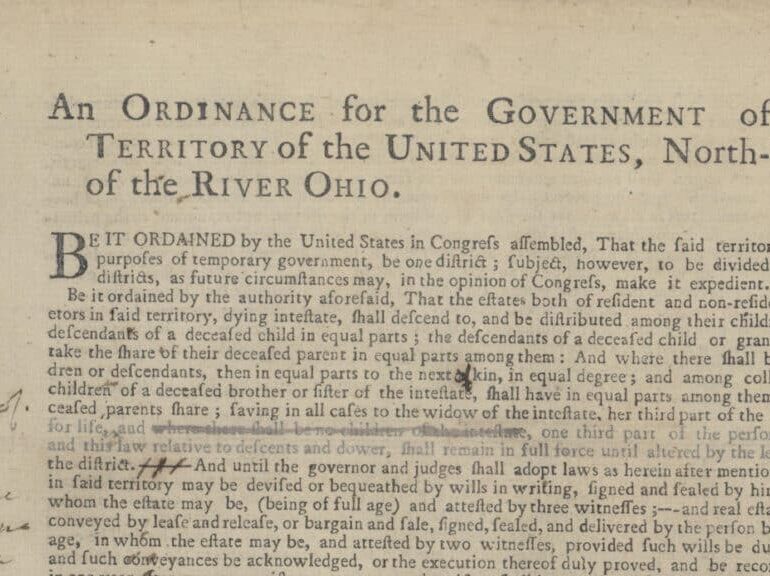

Officially titled “An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio,” it applied to land ceded by the British in the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. It chartered a government for territories north of the Ohio River and outlined a three-stage method to admit new states into the Union. The ordinance eventually led to the formation of Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The territory also included part of what is now Minnesota.

PROHIBITING SLAVERY

Significantly, the Northwest Ordinance banned slavery in the new territories and the language was carried over to the 13th Amendment decades later.

The ordinance evolved from a proposal primarily penned by Thomas Jefferson in 1784 that would have originally applied to southern territories as well as northern ones.

The plan for a temporary government of the Western territory submitted to the Confederation Congress proposed for all states to relinquish territorial claims west of the Appalachian Mountains and divide the area into new states for the union.

In his original draft, Jefferson proposed the following language banning slavery in the territories – both North and South.

“That after the year 1800 of the Christian æra, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the said states, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted to have been personally guilty.”

The anti-slavery clause was narrowly defeated in the Ordinance of 1784. Two years later, Jefferson commented on the defeat, noting that of the 10 states present, six voted for it unanimously, three opposed it, and one delegation was split.

“Seven votes being requisite to decide the proposition affirmatively, it was lost.”

Jefferson bemoaned the vote, writing, “The voice of a single individual of the state which was divided, or of one of those which were of the negative, would have prevented this abominable crime from spreading itself over the new country.”

“Thus we see the fate of millions unborn hanging on the tongue of one man, and heaven was silent in that awful moment! But it is to be hoped it will not always be silent and that the friends to the rights of human nature will in the end prevail.”

But the slavery ban ultimately found its way into the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

“There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”

This language was copied almost verbatim in the first clause of the 13th Amendment in 1865.

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

On January 11, 1864, Missouri Senator John Brooks introduced a proposal for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery. On March 28, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lyman Trumbull submitted a joint resolution as originally introduced by Brooks.

As Constitutional Scholar Kurt Lash pointed out, “The committee based its draft on Jefferson’s language in the Northwest Ordinance.”

Even some who wanted broader language in the 13th Amendment acknowledged they were basing it on Jefferson’s text. For instance, Sen. Charles Sumner said he appreciated that the proposed draft was based on “the old Jeffersonian ordinance, sacred in our history.”

Lash notes that the language in the Northwest Ordinance supported two arguments advanced by abolitionist Republicans.

“First, they refuted the pro-slavery argument that the nation’s Founders were committed to the continuance of chattel slavery. Secondly, the Ordinance proved that the Founders believed they had power to ban slavery in the territories.”

AN EARLY BILL OF RIGHTS

The original draft of the Constitution for the United States didn’t have a Bill of Rights, but the Northwest Ordinance included provisions protecting several natural rights that were a precursor. The National Archives even refers to those sections in the ordinance as a “bill of rights.”

The Philadelphia Convention was meeting when the ordinance was passed, and many of the provisions ultimately found their way into the Bill of Rights four years later.

This early precursor to the bill of rights included several protections within the legal process. It established the writ of habeas corpus and guaranteed trial by jury.

“No man shall be deprived of his liberty or property, but by the judgment of his peers or the law of the land.”

There was also a clause prohibiting “cruel or unusual” punishments and guaranteeing that “all persons shall be bailable, unless for capital offenses, where the proof shall be evident or the presumption great.”

The Northwest Ordinance included protections of property rights, prohibiting any law that would “interfere with or affect private contracts or engagements.”

The Northwest ordinance also included provisions to protect individuals from being “molested on account of his mode of worship or religious sentiments.”

The ordinance described religion, morality, and knowledge as “being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind.” That being the case, “schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.”

The ordinance also included provisions meant to respect and protect the rights of Native Americans.

“The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress.”

In his first term, President George Washington worked to put this policy into practice. Under his administration, treaties were established with seven northern tribes – the Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Chippewa, Iroquois, Sauk, and Fox.

However, as noted by Mt. Vernon, the influx of new settlers in the area, coupled with a lack of meaningful protection of tribal land led to conflicts in the late 18th century.

SUPREME COURT OPINIONS

In recent years, several Supreme Court justices have referred to the Northwest Ordinance as an originalist source to support their opinions.

For instance, in concurring with the majority on Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, Justice Samuel Alito opined that the ordinance highlighted an early understanding of a broad right to the free exercise of religion with “a ‘peace and safety’ carveout.”

Dissenting in another religious freedom case (City of Boerne vs. Flores), Justice Sandra Day O’Connor argued that the Northwest Ordinance supported the position that “around the time of the drafting of the Bill of Rights, it was generally accepted that the right to ‘free exercise’ required, where possible, accommodation of religious practice.”

In Boumediene v. Bush, Justice Anthony Kennedy argued that the Northwest Ordinance answered the question of the limits of the Constitution’s habeas corpus suspension clause due to its extension of the writ to the territories.

And in his concurrence in Timbs v. Indiana, Justice Clarence Thomas invoked the Northwest Ordinance to argue that a prohibition on excessive fines was understood to be “a well-established and fundamental right of citizenship.”

CONCLUSION

On the bicentennial of the Northwest Ordinance, Ronald Reagan declared it “one of the foundation documents of our Nation because it became a model for the Constitution and the Bill of Rights and because of its significance for the expansion of the Union.”

He was right. In particular, the protection of rights expressly listed in the ordinance clearly foreshadowed and influenced the Bill of Rights. And more significantly, it reveals there were significant efforts to address slavery long before the Civil War.

The Northwest Ordinance serves as a powerful reminder. The American experiment in self-government wasn’t born in a single moment, and it didn’t materialize out of thin air at the Philadelphia Convention. It was the culmination of decades of evolving political thought and debate, with the Ordinance foreshadowing the Bill of Rights and the ongoing struggle over slavery.