No Deal: When the British Offered Amnesty in Exchange for Gun Control

By: TJ Martinell

Two months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, the British offered amnesty to all who would lay down their arms. Unsurprisingly, the Patriots didn’t respond too kindly to the deal.

While the “shot heard ‘round the world” is well-known for kicking off the War for Independence on April 19, 1775, what followed soon afterward receives far less attention. The incident provides a textbook example of why you shouldn’t trust gun grabbers.

Although “Taxation without representation” is a common phrase to describe the colonists’ most well-known grievance against British rule, an attempted gun confiscation by General Gage and his troops occupying Boston following the Boston Tea Party actually led to direct conflict between the Redcoats and the colonists.

Indeed, the British had already banned the importation of ammunition and firearms.

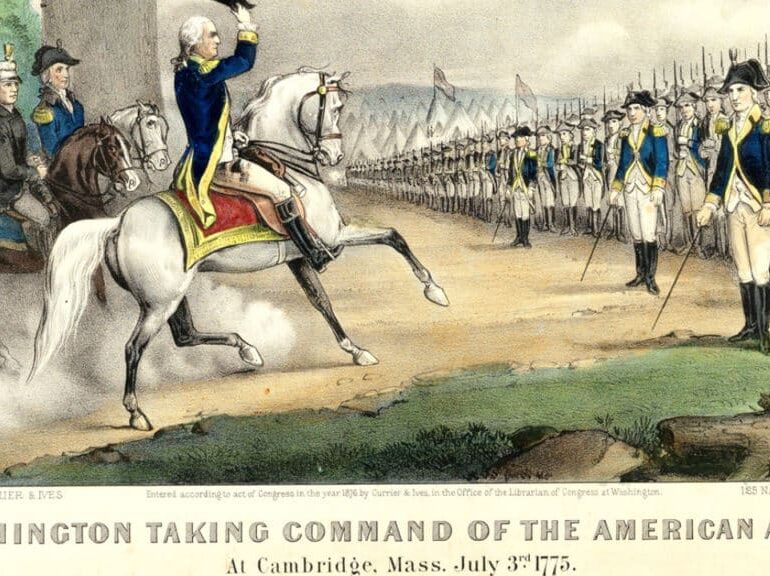

Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the British Redcoats sent to seize those arms returned to Boston while minutemen harassed them along the way. The city was then besieged by colonial militias that had arrived upon hearing of the confrontation by minutemen and British regulars.

Shortly after the siege began, Gage ordered all residents to turn in their firearms “temporarily.” After nearly 2,700 were turned in, the guns were never returned to them, and those promised with safe passage out of the city were prohibited from leaving.

Two months after Lexington and Concord, Gage declared the state of Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion. On June 12, 1775, he offered a general amnesty to all who would lay down their arms. The only two men exempted from pardon were Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Gage said their “offenses are of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment.”

In his pardon letter Gage revealed, unintentionally, how America’s armed populace made it possible for them to resist British gun grabbing efforts:

“A number of armed persons, to the amount of many thousands assembled on the 19th of April last and from behind walls, and lurking holes, attacked a detachment of the King’s troops, who…unprepared for vengeance, and willing to decline it, made use of their arms only in their own defense. Since that period, the rebels, deriving confidence from impunity, have added insult to outrage; have repeatedly fired upon the King’s ships and subjects, with cannon and small arms, have possessed the roads, and other communications by which the town of Boston was supplied with provisions; and with a preposterous parade of military arrangement, they affect to hold the army besieged; while part of their body make daily and indiscriminate invasions upon private property, and with a wantonness of cruelty every incident to lawless tumult, carry degradation and distress wherever they turn their steps…”

The Second Continental Congress responded less than a month later with a “Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms” written by Thomas Jefferson and John Dickinson.

The declaration lambasts Gage for his attacks on the conduct of colonists under military occupation:

“The General, further emulating his Ministerial masters, by a Proclamation, bearing date on the 12th day of June, after venting the grossest falsehoods and calumnies against the good people of these Colonies, proceeds to ‘declare them all, either by name or description, to be rebels and traitors; to supersede the course of the common law, and instead thereof to publish and order the use and exercise of the law martial.’ His troops have butchered our countrymen; have wantonly burnt Charlestown, besides a considerable number of houses in other places; our ships and vessels are seized; the necessary supplies of provisions are intercepted, and he is exerting his utmost power to spread destruction and devastation around him.” [Emphasis added]

The declaration also makes it clear that, though the siege was still ongoing, word of Gage’s gun confiscation measures had gotten out, and left an indelible impression on Americans whom Gage now demanded turn in their arms as well.

“The inhabitants of Boston, being confined within that Town by the General, their Governour, and having, in order to procure their dismission, entered into a treaty with him, it was stipulated that the said inhabitants, having deposited their arms with their own Magistrates, should have liberty to depart, taking with them their other effects. They accordingly delivered up their arms; but in open violation of honour, in defiance of the obligation of treaties, which even savage nations esteemed sacred, the Governour ordered the arms deposited as aforesaid, that they might be preserved for their owners, to be seized by a body of soldiers; detained the greatest part of the inhabitants in the Town, and compelled the few who were permitted to retire, to leave their most valuable effects behind.”

The declaration then asserts the right of Americans to continue resisting Gage and other enforcers of British rule, through use of arms:

“In our own native land, in defence of the freedom that is our birth-right, and which we ever enjoyed till the late violation of it; for the protection of our property, acquired solely by the honest industry of our forefathers and ourselves, against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms. We shall lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, and not before.” [Emphasis added]

It’s not terribly difficult to understand the thinking behind the Declaration. Gage had demanded people surrender their arms before, then went back on his word once they had done so. Why would anyone, especially those besieging him and his troops, trust him not to do so again when their means of defending themselves were removed?

Never trusting gun grabbers is a lesson modern Americans would do well to heed.