Lessons from Birmingham Jail

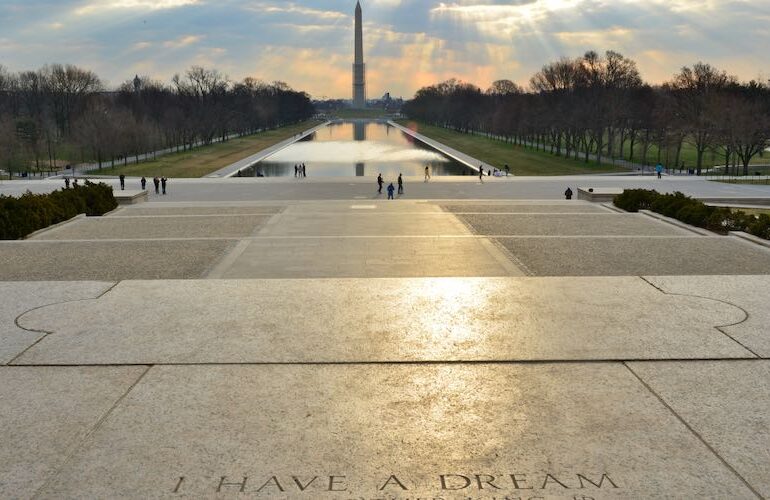

Just four months before Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, he sat alone in a jail cell in Birmingham, Alabama, reading an open letter. Penned by eight local clergymen, it branded King and his colleagues “outsiders,” accused them of extremism, counseled them to be more patient so “law and order” and “common sense” would have time to do their work, and urged them not to break laws. King, whose conditions of confinement were so severe that he lacked paper on which to write, began scribbling his responses in the margins of the local newspaper in which the letter had been published. Within just four days, he had produced what we now know as the “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which represents the epistolary forerunner and counterpart of his most famous speech.

Penned 60 years ago this year, King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” remains refreshingly forthright in its religious conviction. Addressed to “My fellow clergymen,” it is chock full of references to Biblical figures and stories, appealing to God by name no fewer than five times. King himself is first and foremost a preacher and a prophet, someone interpreting contemporary events from a God’s-eye point of view. This deeply religious perspective means that King would have grave doubts about contemporary efforts to combat racism in purely secular terms, which often assume that the concept of race must be affirmed as both real and necessary if racism is to be combatted. His Christian commitments helped him to articulate a response to racism that was rooted in both the natural law tradition and in a kind of Christian personalism, focused on the things that all human beings share. I believe that this perspective would powerfully shape King’s view of today’s polemics concerning “systemic racism.”

King‘s religion was bequeathed to him by his father, who was also the son and grandson of preachers. Known as Michael King, his father changed both his name and his 5-year-old son’s to Martin Luther King after attending a 1934 Baptist World Alliance conference in Berlin. Martin Luther King Jr. would share with his sixteenth-century namesake a similar mission of protest, making good on the pledge of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a group he led, to come to the aid of any of its 85 chapters that felt compelled to engage in direct action against segregation. It was that pledge that brought him to Birmingham, as segregated a city as any in the union.

King emphasizes not the incommensurability of different racial perspectives, such as the view that a white woman could never understand what it is like to be a black man, but the mutuality and oneness of humankind.

Because King viewed himself through the lens of Biblical apostles and prophets, he understood himself to have an obligation to preach fundamental truths that were applicable to all human beings. In responding to the clergymen’s charge that he represented an outside agitator, King invokes the principle of justice, writing, “I am in Birmingham because injustice is here,” and immediately citing Biblical precedents. The Old Testament prophets had left their homes and carried the message of “Thus saith the Lord” to other places, and the apostle Paul had spread his message throughout the Graeco-Roman world, so now it was King’s turn to carry the Lord’s word wherever it is most needed. Informed by such a perspective, King’s voice rings forth biblically: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” King emphasizes not the incommensurability of different racial perspectives, such as the view that a white woman could never understand what it is like to be a black man, but the mutuality and oneness of humankind.

This Biblical perspective informs King’s response to the charge of extremism. For one thing, he and his colleagues operate in a middle zone between complacency and militancy, having chosen the path of nonviolent action. More importantly, they have been quite measured in their deliberations, taking time to verify the facts of injustice, attempting (unsuccessfully) to negotiate, purifying their sense of mission, and eschewing violence. Most importantly of all, he asserted, they have recognized that throughout history, freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. To adopt such a middle course is to eschew violence in all its forms, including verbal violence. This means not closing one’s ears or seeking to shout down an opponent but listening to others’ points of view and engaging in real dialogue, seeking as much to understand as well as to be understood. When the shouting gets too loud, dialogue becomes impossible.

Many of King’s arguments clearly presume that his readers recognize and share fundamental natural law assumptions about moral responsibility and human dignity. King invites the pastors to consider their shared identity as parents. Imagine what it is like, he says, when you “suddenly find yourself tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see the tears welling up in her little eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see the depressing clouds of inferiority begin to form in her little mental sky, and see her begin to distort her little personality by unconsciously developing a bitterness toward white people.” Or when you “have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking in agonizing pathos, ‘Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?’” King’s implicit message – the key to ending racism is not to accentuate divisions but to focus on our shared responsibility to the next generation.

The clergymen urge patience, but King can rightfully retort that blacks in America have waited 340 years for their constitutional and God-given rights to be respected. “Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever,” he writes, and “something within the American negro has reminded him of his birthright of freedom.” Again and again, King has hoped that the religious leaders of the community would see the justice of his cause, but again and again, such hopes have been thwarted. Yet King continues to focus on the color-blindness of civil and moral law, urging his interlocutors to remember that “The negro is your brother.” What matters is not a pastor’s race. What matters is that too many pastors have remained on the sideline. They need to realize that segregation is more than a “social issue” over which “the Gospel has no real concern.” From a Biblical perspective, racism is a problem for every person.

King answers the charge that he is promoting lawlessness by echoing the Biblical distinction between rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s and rendering to God what is God’s. There are civil laws and there are natural and God-given laws, he says. A just law is one that squares with the moral law and the law of God. An unjust law, by contrast, is out of harmony with moral law. Such laws give oppressors a false sense of superiority and the oppressed a false sense of inferiority. When people try to impose on others a law they do not intend to obey themselves, they are engaged in injustice. The segregation laws of Alabama are unjust because they bind a minority that had no role in their passage – many counties in the state, even those that are majority black, have not a single black registered voter. Simply put, any policy that discriminates between people based on race cannot be just, and no truly faithful person can abide it.

King’s religious tradition powerfully grounded his conviction that all people are equal in the eyes of God, rendering race a decrepit concept. Moreover, it instilled a particular sense of responsibility to the poor and oppressed. Jesus does not spend his time with the rich and famous, scheming to acquire power and fame. Instead, he is regularly found among the poor, the downtrodden, and the outcast. He taught his followers that they would be recognized by how they treated the oppressed, the imprisoned, and “the least of these my brothers.” A person’s race tells us nothing about their character or whether we should extend to them our compassion and friendship. God does not discriminate based on skin color, and neither should human beings.

Modern racial discourse is often divisive and unforgiving, with no clear path to unity or healing. In the Bible Martin Luther King Jr. found some of his most powerful rhetorical resources, but also his deepest source of inspiration and resilience concerning the brotherhood of all humankind. When he closes his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” with the hope that it finds his fellow clergymen “strong in the faith,” he is not engaged in mere niceties. He is pinning his hopes on it, knowing that consciences formed in the Christian faith could never abide the abuse of humanity they were witnessing in Birmingham. The answer to racist discrimination is not anti-racist discrimination but shared commitment to a vision of justice that goes beyond race. Unlike many contemporary critics of racism, King sought not to emphasize racial differences but to dissolve them, in a prophetic dream that a day would dawn when no human being would be seen through the lens of race.