Law to End State Cooperation with the Enforcement of Presidential Executive Orders

BISMARCK, N.D. (Aug. 1, 2021) – Today a North Dakota law that creates a process to end state cooperation with the enforcement of presidential executive orders went into effect. The state will opt out of enforcement if the attorney general issues an opinion that the executive order unconstitutionally restricts a person’s rights.

A coalition of nine Republicans introduced House Bill 1164 (HB1164) on Jan 8. Gov. Doug Burgum signed the bill into law on April 23, after it passed both the House and Senate with strong majorities. The legislation revises N.D. Cent. Code § 54-03-32 requiring the state attorney general to review any presidential executive order not affirmed by a Congressional vote on the recommendation of the Legislative Management.

The state, its political subdivisions, and any publicly-funded organization are prohibited from implementing any presidential executive order in the following categories that the North Dakota attorney general determines to be unconstitutional during review, or that have been found unconstitutional by a court of competent jurisdiction:

a. Pandemics or other health emergencies;

b. The regulation of natural resources, including coal and oil;

c. The regulation of the agriculture industry;

d. The use of land;

e. The regulation of the financial sector as it relates to environmental, social, or governance standards; or

f. The regulation of the constitutional right to keep and bear arms.

THE PROCESS IN PRACTICE

The enactment of HB1164 creates a process to potentially push back against overreaching executive authority. Upon the AG’s determination that an EO is unconstitutional, the state will be required to withdraw all resources and cease any cooperation with enforcement or implementation of the action.

But the process will never even begin unless Legislative Management chooses to review a specific EO. While the law requires the attorney general to review any executive order referred to him/her by Legislative Management, the new law says Legislative Management “may review.” That leaves it to that body’s discretion. Even if it does initiate a review and send the EO off to the AG, the process then rests in the hands of a politically connected lawyer.

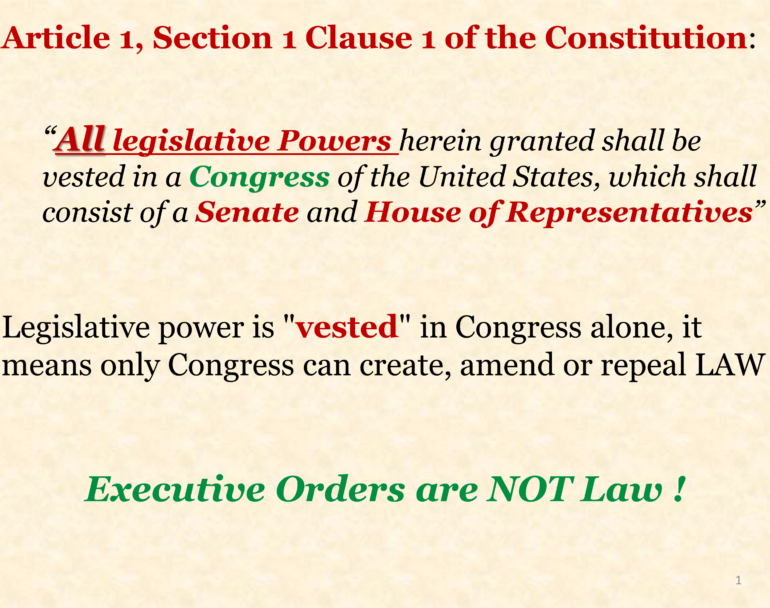

In the second place, this cumbersome review process isn’t even necessary. The legislature already had the authority to review executive orders and prohibit their implementation for any reason whatsoever. In fact, the legislature could simply pass a bill prohibiting state enforcement of specific types of executive orders without any lengthy and unwieldy constitutional review. The state has the right to direct its personnel and resources as it sees fit. It can prohibit the enforcement of federal laws or the implementation of federal programs for any reason at all. North Dakota could withdraw state resources from the enforcement of federal acts just because it’s Tuesday and there’s snow on the ground.

LEGAL BASIS

Based on five major cases dating back to 1842, the anti-commandeering doctrine holds that the federal government cannot force states to help implement or enforce any federal act or program – whether constitutional or not. Printz v. U.S. (1997) serves as the cornerstone.

“We held in New York that Congress cannot compel the States to enact or enforce a federal regulatory program. Today we hold that Congress cannot circumvent that prohibition by conscripting the States’ officers directly. The Federal Government may neither issue directives requiring the States to address particular problems, nor command the States’ officers, or those of their political subdivisions, to administer or enforce a federal regulatory program. It matters not whether policy making is involved, and no case by case weighing of the burdens or benefits is necessary; such commands are fundamentally incompatible with our constitutional system of dual sovereignty.”

No determination of constitutionality is necessary to invoke the anti-commandeering doctrine. State and local governments can refuse to enforce federal laws or implement federal programs whether they are constitutional or not.

In Murphy v. NCAA (2018), the Court held that Congress can’t take any action that “dictates what a state legislature may and may not do” even when the state action conflicts with federal law. Samuel Alito wrote, “a more direct affront to state sovereignty is not easy to imagine.” He continued:

The anticommandeering doctrine may sound arcane, but it is simply the expression of a fundamental structural decision incorporated into the Constitution, i.e., the decision to withhold from Congress the power to issue orders directly to the States … Conspicuously absent from the list of powers given to Congress is the power to issue direct orders to the governments of the States. The anticommandeering doctrine simply represents the recognition of this limit on congressional authority.