Anti-Federalists Strike Back: Two Responses to James Wilson’s State House Speech

By: Bob Fiedler

On September 17, 1787, the Philadelphia Convention, finished drafting the U.S. Constitution. The Anti-Federalists wasted no time in denouncing the document. The first stand-alone counterattack against the anti-federalists took place in Philadelphia on October 6, 1787, when James Wilson delivered his “State House Speech.”

Anti-federalist opponents of ratification took up their pens to counter the arguments Wilson made in his speech.

A Democratic Federalist – “What Shelter From Arbitrary Power?” Published October 17, 1787

Some believe Tench Coxe used the penname “A Democratic Federalist,” though this essay bears little resemblance to anything known to have been authored by him. While the identity of the author is still debatable, what is not debatable is the author’s uncanny ability to look to legal theory and history to illustrate some of the deep flaws in Wilson’s argument.

A Democratic Federalist points to Wilson’s assurance that the difference between the state constitutions and the federal constitution is that in the former, every power which is not reserved is given, while in the latter every power which is not given is reserved.

“If this doctrine is true, and since it is the only security that we are to have for our natural rights, it ought at least to have been clearly expressed in the plan of government… The present articles of confederation say: Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, AND EVERY POWER, JURISDICTION AND RIGHT WHICH IS NOT BY THIS CONFEDERATION EXPRESSLY, DELEGATED TO THE UNITED STATES IN CONGRESS ASSEMBLED. This declaration (for what purpose I know not) is entirely omitted in the proposed Constitution.”

He also provides one of the earliest examples of inconsistencies regarding the federal judiciary that would later be championed by the anti-federalist Brutus. This includes the phrasing in the “cases and controversies clause” (Article III, § 2) that he points out invests the federal judiciary with the power to overturn any ruling made by state court judges and juries, and the fact that the right to trial by jury in civil cases is seemingly abolished entirely.

Furthermore, in any conflict of jurisdiction between the state and federal courts, he points out that the general government will always maintain an advantage in the balance of power. He offers as an example, that in all matters of diversity jurisdiction (cases between citizens of different States) the federal court has original jurisdiction.

…. Suppose therefore, that the military officers of congress, by a wanton abuse of power, imprison the free citizens of America, What satisfaction can we expect from a lordly court of justice, always ready to protect the officers of government against the weak and helpless citizen… What refuge shall we then have to shelter us from the iron hand of arbitrary power?

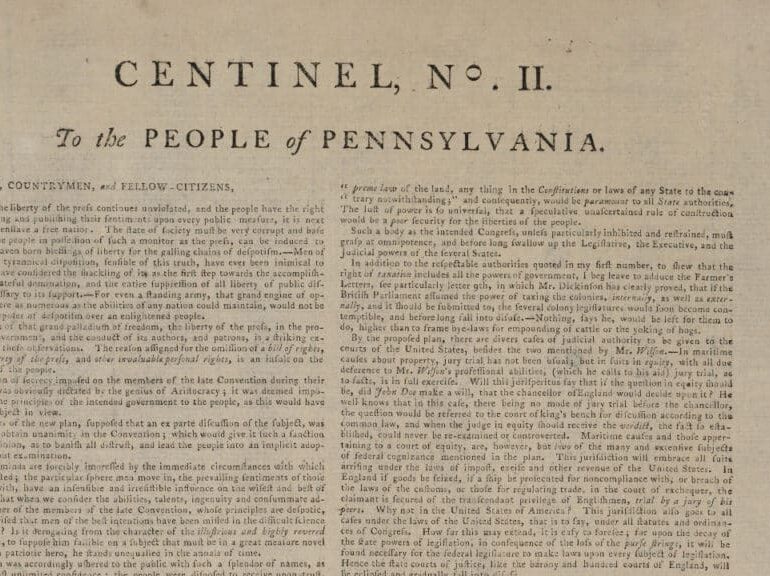

CENTINEL II – Freeman’s Journal (Philadelphia), October 24, 1787

Samuel Bryan of Pennsylvania most likely wrote under the penname Centinel. In his second essay, he focused on the lack of protection for a free press.

“As long as the liberty of the press continues unviolated, and the people have the right of expressing and publishing their sentiments upon every public measure, it is next to impossible to enslave a free nation.”

Centinel’s response to James Wilson’s speech captures the extent of distrust many felt toward the newly-proposed government in the Constitution. He warned that those who govern are continually engaged in a “silent, powerful” conspiracy to deprive the people of their rights and liberties. Indeed, the lust of power is so universal, that a speculative unascertained rule of construction would be a poor security for the liberties of the people.

Men of an aspiring and tyrannical disposition, sensible of this truth, have ever been inimical to the press.

Centinel argues that the freedom of the press must be implemented through a bill of rights, and other rights must be included as well.

Centinel also concluded, through comparison to Ancient Rome, that the states could easily be rendered superfluous under the proposed Constitution. This is a curious comparison, however. It must be noted that Ancient Rome, on some level, embraced tyranny and despotism in a way that Americans may not realize. For example, it was not uncommon in the Roman Republic for a dictator to assume power for years at a time, to weather a crisis, and then to relinquish that dictatorship after the crisis had subsided. The noble relinquishment of that dictatorial power wrote Cincinnatus into history. Americans’ only engagement with such absolute power was the British Crown, which had notable differences from Ancient Rome and the American colonies.

Regardless, Centinel’s analysis of James Wilson’s speech deserves attention for another reason: no matter what assurances are given and accommodations made, there will always be some discontent. Unanimity, particularly in formulating the structure of government, is not a realistic possibility. Centinel’s distrust and insistence on changing the Constitution, however, captures the spirit that led to the adoption of the Bill of Rights and expansion of protections for the people, and for that, Americans can be thankful.