Virginia Association of 1769: A Step Toward Continental Unity

By: Mike Maharrey

In May 1769, Virginia took a decisive step beyond carefully worded protests by launching an organized and strategic boycott against British goods. Led by George Washington and George Mason, the Virginia Association adapted northern resistance models to fit local circumstances and laid critical groundwork for revolutionary unity and economic self-reliance.

The Association became part of a growing and coordinated colonial response to the Townshend Acts – a series of laws that imposed new taxes on imported paper, paint, lead, glass, and tea, and expanded the British government’s power to fight smuggling.

While historians often focus on resistance in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York during the early years of the American Revolution, Virginia’s actions were crucial threads in the broader fabric of unified colonial resistance to British government overreach.

VIRGINIA’S TRADITION OF RESISTANCE

Resistance to British overreach in the American colonies first stirred with opposition to the Writs of Assistance in 1761 and intensified into direct resistance with the passage of the Stamp Act in 1765. Virginia was a key player in the fight against the Stamp Act, with Patrick Henry’s Stamp Act Resolves galvanizing resistance throughout the colonies.

Colonial opposition to the Stamp Act ultimately made it impossible to enforce. On March 18, 1766, Parliament relented and repealed the hated tax. However, the move did nothing to ease tensions.

That same day, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act, asserting that it had the authority to make laws binding the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” This set the stage for the next confrontation: the Townshend Acts.

BUILDING THE CASE AGAINST PARLIAMENT

John Dickinson, a prominent Pennsylvania lawyer, emerged as a leading voice against British taxation.

In response to the Townshend Acts, Dickinson wrote a series of essays titled Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, published in The Pennsylvania Chronicle in 1767 and 1768. The impact of the Letters was wide-ranging, with the essays reprinted in most major colonial newspapers.

The Letters laid out a constitutional argument, conceding that the British had the authority to regulate trade, but asserting that Parliament did not have the right to use internal taxation to raise revenue from the colonies.

Dickinson’s arguments helped lay the foundation for broader colonial opposition to the Townshend Acts and strengthened their views about constitutional limits on British power.

Resistance to the Townshend Acts gained momentum in Massachusetts after Dickinson sent copies of his essays to James Otis Jr. In his cover letter, Dickinson lamented, “The liberties of our Common Country appear to me to be at this moment exposed to the most imminent danger.”

“My opinion of your love for your country induces me to commit to your hands the inclosed letters to be disposed of as you think proper.”

THE MASSACHUSETTS CIRCULAR LETTER

Motivated by this exchange, Otis joined Samuel Adams in drafting the Massachusetts Circular Letter, which built on the Farmer’s arguments and carried them into formal legislative protest.

The Massachusetts legislature approved the letter in February 1768, and it quickly circulated throughout the colonies.

The thrust of the argument was that the taxes were unconstitutional because the people of Massachusetts were not represented in Parliament.

“It is, moreover, their humble opinion … the Acts made there, imposing duties on the people of this province, with the sole and express purpose of raising a revenue, are infringements of their natural and constitutional rights; because, as they are not represented in the British Parliament, his Majesty’s commons in Britain, by those Acts, grant their property without their consent.”

Otis and Adams argued that the meaning of a constitution – even the unwritten British Constitution – could not be altered at the whim of Parliament. Such arbitrary power, they warned, would destroy the foundation of the constitutional system itself.

Inspired by these arguments – and aware of growing boycotts in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia – Virginia’s leaders began to take action.

VIRGINIA PROTEST

Resistance to the Townshend Acts began building in Virginia after the Massachusetts Circular Letter was read aloud in the House of Burgesses on April 2, 1768. Two weeks later, the assembly adopted formal protests that were sent to the King and Parliament.

In their petition to the King, the Virginians lamented the adoption of the Townshend Duties, which they asserted were, “derogatory to those Constitutional Privileges and immunities, which they, the Heirs and Descendants of free born Britons, have ever esteemed their unquestionable and invaluable birth Rights.”

A lengthier petition sent to the House of Commons began by reminding British lawmakers that the Virginia assembly was “the sole constitutional Representatives of his Majesty’s most dutiful and loyal Subjects [in] Virginia.”

The Burgesses further emphasized that Virginians were merely asserting “the common unquestionable Rights of British Subjects, who, by a fundamental and vital Principle of their Constitution cannot be subjected to any kind of Taxation or have the smallest Portion of their Property taken from them by any Power on Earth without their Consent given by their Representatives.”

The petition ended with a warning.

“British Patriots will never consent to the Exercise of anti-constitutional Powers, which, even in these remote corners, may in Time prove dangerous in their Example to the interior parts of the British Empire.”

Around the same time, the Virginia Gazette published a letter by Arthur Lee, writing under the pseudonym “Monitor,” calling on Virginians to prioritize American goods over British imports and laying the early groundwork for a formal association.

Monitor asserted, “The preservation of our country demands; that we may not be under a dangerous and slavish dependance on any other people.”

He included language to form the proposed association.

“We the underwritten do agree, and solemnly promise to prefer on every occasion, the manufactures of America, to those of every other country; and to promote with the utmost of our abilities, American manufactures, so far as to furnish ourselves with the necessaries of life.”

He went on to point out, “The beneficial influence of associations, and institutions of the same kind, on the progress of manufactures, has been too often experienced to be now questioned.”

These ideas gained traction in Virginia. By the spring of 1769, leaders including George Washington and George Mason moved to organize a formal, colony-wide non-importation agreement.

PLANNING THE ASSOCIATION

In the spring of 1769, George Washington and George Mason privately collaborated on a plan to organize a formal boycott of British goods in Virginia.

After receiving a letter from Dr. David Ross that included a copy of the Philadelphia non-importation agreement, Washington sent a letter to Mason on April 5, floating the idea of a Virginia boycott.

He noted that “the northern Colonies, it appears, are endeavouring to adopt this scheme – In my opinion it is a good one.”

He continued, saying the more he considered the idea, “the more ardently I wish success to it, because I think there are private, as well as public advantages to result from it.” He then warned, “I have always thought that by virtue of the same power (for here alone the authority derives) which assumes the right of Taxation, they may attempt at least to restrain our manufactories.”

On April 23, 1769, Mason sent Washington a draft outlining a non-importation association that would establish a boycott of British goods.

As Mason phrased it, Virginians agreed they would not “at any time hereafter directly or indirectly import or cause to be imported any Manner of Goods Merchandize or Manufactures which are or shall hereafter be taxed by Act of Parliament for the purpose of raising a Revenue in America.” [Emphasis added]

The proposed boycott drew inspiration from northern efforts but was carefully adapted to Virginia’s unique economic conditions. For example, Washington and Mason exempted inexpensive cloth used to clothe enslaved laborers – a practical adjustment recognizing the realities of plantation life. At the same time, they maintained pressure on British luxury goods.

Mason’s draft not only targeted goods taxed under the Townshend Acts, but also committed the signers to reject a wide range of imported luxuries in an effort to discourage extravagance, strengthen colonial self-reliance, and resist British cultural influence.

These luxuries included:

- Alcoholic beverages: wines, rum, brandy, distilled spirituous liquors, malt liquors

- Transportation: horse carriages

- Luxury fabrics: superfine cloth, silk, satin, cambric, lawn, muslin, gauze

- Fashion accessories: feathers

- Clothing accessories: ribbons, thread laces, millinery

- Jewelry and precious materials: gold lace, silver lace, gold thread, silver thread, gold and silver jewelry

- Household and decorative goods: glazed earthenware, china ware, household furniture, upholstery, paper hangings, looking glasses

- Leisure and gaming items: playing cards, dice

Significantly, the agreement also pledged that, “they will not import any Slaves, or purchase any (hereafter) imported untill the said Acts of parliament are repeale’d.”

FORMAL ACTION

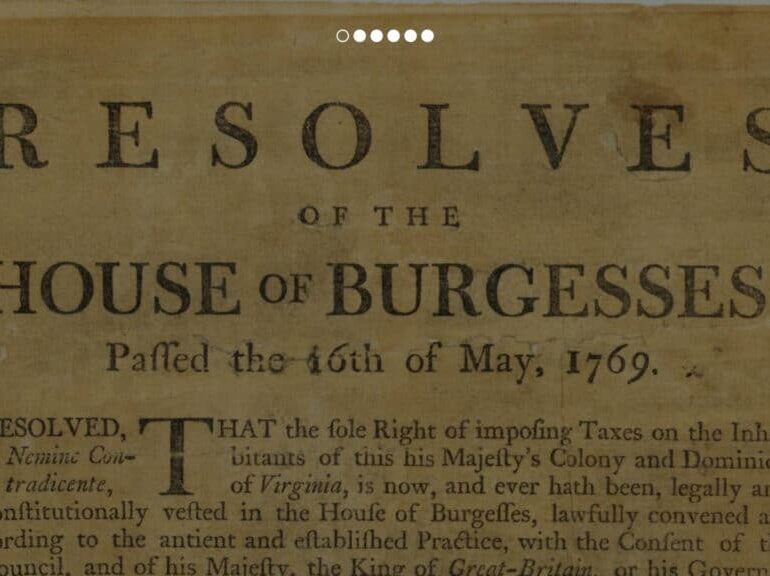

Tensions escalated on May 16 when the House of Burgesses passed a resolution declaring British taxes on the colonies illegal.

“RESOLVED … That the sole Right of imposing Taxes on the Inhabitants of this his Majesty’s Colony and Dominion of Virginia, is now, and ever hath been, legally and constitutionally vested in the House of Burgesses …”

It didn’t take long for the Royal Governor of Virginia to respond by dissolving the Virginia legislature. Washington recorded what happened in his diary the following day.

“About noon Speaker Randolph received a message from Governor Botetourt commanding the burgesses to come immediately to the council chamber. When they were assembled there, Botetourt spoke: ‘Mr. Speaker, and Gentlemen of the House of Burgesses, I have heard of your Resolves, and augur ill of their Effect. You have made it my Duty to dissolve you; and you are dissolved accordingly.’”

As Washington described it, the Virginians were undeterred. The members of the House of Burgesses “reassembled a few doors down the street at Hay’s Raleigh Tavern, meeting unofficially in the Apollo Room to consider ‘their distressed Situation.’”

By regrouping outside official channels, the Burgesses took a revolutionary step – organizing independent political action without royal approval. This laid the groundwork for self-government.

Peyton Randolph was elected moderator of the group. He immediately organized a committee to “prepare a plan for a Virginia nonimportation association,” where Washington introduced Mason’s draft.

With only a few revisions, the members of the House of Burgesses approved the non-importation agreement on May 18. The document, “being read, seriously considered, and approved, was signed by a great Number of the principal Gentlemen of the Colony then present, and is as follows.”

IMPACT

Virginia’s Association fit into a wider pattern of colonial resistance. Merchants and political leaders in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia had already adopted non-importation agreements. Virginia’s move helped build momentum toward a coordinated continental effort, culminating in the formation of the Continental Association in 1774.

There was no way to enforce the association. The boycott was relatively ineffective during the first couple of years. According to Encyclopedia Virginia, “imports from Great Britain into the Chesapeake region increased dramatically during the first year of the nonimportation association.”

However, imports of luxury goods and many targeted items eventually began to decline, indicating that the pact wasn’t a total failure.

It also set a foundation for further action. In 1770, supporters of the association, led by Mason and Richard Henry Lee, proposed boycotting merchants who violated the agreement and recommended the formation of county committees to enforce its provisions.

In June, an expanded group signed a revised association.

One of the most significant impacts of the original association was symbolic. It sent a clear message to the northern colonies – Virginia has your back.

It also let the British know that the American colonies could present a united front. As History.com noted: “The mere existence of non-importation agreements proved that the southern colonies were willing to defend Massachusetts, the true target of Britain’s crackdown, where violent protests against the Townshend Acts had led to a military occupation of Boston, beginning on October 2, 1768.”

This positioned Virginia as a leader in commercial resistance to British taxation. The Virginia Association and the united front it established set the stage for the Continental Association, passed in 1774.

This document created a formal agreement between the 12 colonies represented in the Congress (Georgia did not send delegates) to boycott British goods.

Richard Henry Lee was the driving force behind the Continental Association, and he used the Virginia Association as a template.

The adoption of the Continental Association was a significant step in resistance to Parliament. It demonstrated the colonies’ willingness and ability to work together in a coordinated way.

It also drew a concrete line in the sand, letting the British know that the colonies were not just going to protest – they were willing to take concrete actions to resist unconstitutional and tyrannical actions.

In taking early, organized action, Virginians set an important precedent. They refused to wait for liberty to be handed to them – instead, they acted and helped lead the charge to secure it.